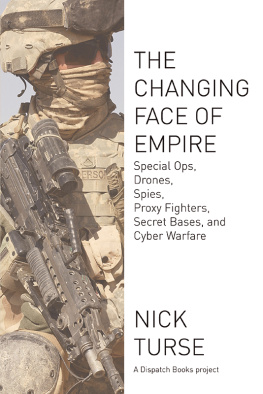

Introduction

Tomorrows Battlefield

On July 12, 2013, as the shrill whistle of a boatswains call sounded, a cadre of officers from elite military units assembled in a bare-bones building at a US military base in Boeblingen, Germany. On a stage, in front of a humongous American flag, Captain Robert Smith, commanding officer of Naval Special Warfare Group Two; Captain J. Dane Thorleifson, outgoing commander of Naval Special Warfare Unit Ten; and Captain Jay Richards, his successor, took part in a time-honored naval tradition: the change of command ceremony. Before a small crowd of uniformed military personnel and a few civilians, these men, all members of Special Operations Command Africa (SOCAFRICA), spoke about something rarely mentioned in public: covert US military missions in Africa.

By the summer of 2013, representatives of U.S. Africa Command (AFRICOM), the newest of the Defense Departments six geographic combatant commands and the umbrella organization for operations on the continent, had told me again and again that the US military presence there was small, circumscribed, episodic, and, above all, benign. Nothing much of note, they insisted, was going on in Africa. At this closed-door ceremony, before a select crowd of insiders, the officerswhose units include elite Navy SEALs and others expert in counterterrorism missions and capable of launching raids from ships, submarines, and aircraftoffered a very different picture of military operations.

The mission of Naval Special Warfare Unit Ten does not pause, Smith told the audience. Forces are deploying, as we speak, down on the African continent. Forces are already staged on the African continent executing the Naval Special Warfare Unit Ten mission, the SOCAFRICA mission, and the AFRICOM mission. That mission does not stop. He added, Some people like to think that Africa is our next ridgeline, and then set his audience straight. Africa is our current ridgeline.

Smith also described partnerships with African militaries across the continent, from Uganda to Somalia to Nigeria, while lauding departing commander Thorleifsons efforts: He has led this fight with his own boots on the ground in Africa. That caught my attention. It sure didnt sound like the standard AFRICOM line about a small footprint on the continent, mostly involving humanitarian operations. It sounded as if he was saying that America was already at war in Africa.

Smith presented Thorleifson with the Legion of Merit, in part for creating a strategy for persistent engagements in five Special Operations Command Africa priority countries. Then Thorleifson took to the lectern himself and offered an even more striking vision of US operations.

Reflecting on two years spent commanding Naval Special Warfare Unit Ten, he discussed the high tempo of operations, with personnel deployed 365 days a year in over half a dozen disparate, austere locations and lauded his troops for successfully operating in a complex battlespace. Then he quoted his boss, then Brigadier (now Major) General James Linder, the commander of US Special Operations forces in Africa, looking on from the audience. General Linder has been saying, Africa is the battlefield of tomorrow, today. And, sir, I couldnt agree more. This new battlefield is custom made for SOC and well thrive in it. Its exactly where we need to be today and I expect well be for some time in the future.

My ears perked up. The commander of a shadowy quick-reaction force agreeing with his commander, the chief of the most elite American troops in Africa, that the continent wasnt a sleepy backwater, as AFRICOMs spokespeople and public affairs personnel claimed; it wasnt even the war zone of tomorrow. It was todays battlefield. This hush-hush ceremony corroborated exactly what my own reporting had uncovered over the previous year and convinced me that I needed to keep digging into just what the U.S. military was doingfar from prying eyeson the African continent.

The Great AFRICOM Runaround

The path that led me to this point was, like so many others in life, winding and unexpected. For years, as I investigated other wars elsewhere on the planet, I half-noticed stories about US military activities in Africa but paid them no serious attention. I did a little digging once or twice, but nothing came of it. In 2005, I wrote a short chapter on US military missions in Africa for my first book, but it ended up on the cutting-room floor. At one point, the military even offered me an opportunity to visit its lone avowed base on the continent, Camp Lemonnier in the tiny Horn of Africa nation of Djibouti, but I had no media outlet interested in paying my way and so never went.

In 2010, with the Iraq War winding down and a presidential promise that the same would eventually happen in Afghanistan, I began to note mounting evidence of increasingly robust US military activity in Africa. By the next year, I was sure something big was happening, so I took the idea to my boss at a news website where I had just been made a senior editor. Sitting in a chain eatery in New York City, I pitched the idea of a big investigative piece on shadowy US military operations in Africa. His face said it alland then so did his mouth. Nobody is interested in Africa, readers wont care, and he didnt want me wasting time on a deep-dive investigation into a hopeless nonstory. I got the message loud and clear. Luckily Tom Engelhardt, my editor and colleague at TomDispatch.com, had the exact opposite reaction to my pitch and encouraged me to get started.

By the time I cleared out other projects and set to work, it was 2012 and, on July 12exactly one year to the day before the change of command ceremony in Boeblingen and following a considerable amount of investigation of open-source material and little-noticed military documentsI published Obamas Scramble for Africa: Secret Wars, Secret Bases, and the Pentagons New Spice Route, now the first chapter of this book. More than two years later, Im still at it, still digging into US. military missions in Africa, sifting through formerly classified documents and restricted reports and, on occasion, reporting from the continent.

I never intended to make Africa my beat. That initial article could easily have been a one-off piece and I might have returned to coverage of the US war in Afghanistan or global drone operations or begun researching US military missions in South America or something else entirely. What spurred me to stick with Africa were the reactions of US Africa Command.