Copyright 2016

Steven R. Koltai

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the Brookings Institution Press, 1775 Massachusetts Avenue, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20036, www.brookings.edu.

The Brookings Institution is a private nonprofit organization devoted to research, education, and publication on important issues of domestic and foreign policy. Its principal purpose is to bring the highest quality independent research and analysis to bear on current and emerging policy problems. Interpretations or conclusions in Brookings publications should be understood to be solely those of the authors.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data are available

ISBN 9-780-8157-2923-5 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN 9-780-8157-2924-2 (ebook)

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Typeset in Electra

Composition by Westchester Publishing Services

Preface

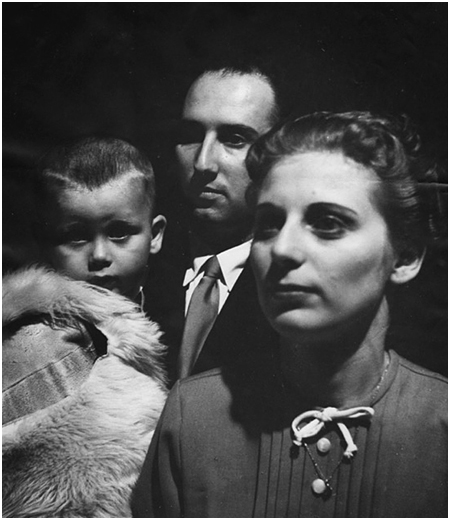

TWENTY-FOUR HOURS. THATS HOW much tim e the young parents had to plan their departure. They packed two suitcases, stuffing them with identity papers, diplomas, and the few clothes they could carry. They picked up their two-year-old son and, on their way out the door, grabbed his teddy bear. They left food in the fridge and dishes in the sink. They seemed to be heading on a quick errand. In fact, they were going out for the rest of their lives.

Of course they were scared. Who wouldnt be? It was freezing cold, soldiers were firing real bullets, and they had never been abroad, except for the one time the father journeyed in a cattle car to the Theresienstadt childrens work camp courtesy of the Nazis. But the family believed that whatever future lay ahead would be better than the present of communism or the horror they had lived during the Second World War.

This was Hungary in November 1956. As Soviet tanks rumbled through Budapest, suppressing the largest armed insurrection in the half-century history of the Soviet-occupied countries of Eastern Europe, some 200,000 Hungarians fled the violence, degradation, surveillance, and economic straightjacket of the so-called Hungarian Peoples Republic. Too young to have escaped during World War II, the parents now had a chance to slip through a brief parting in the iron curtain. Just weeks before, students from Budapests Technical University had led tens of thousands of protesters to the city center, where they had sliced the communist coat of arms from Hungarian flags and yanked down a statue of Joseph Stalin. The young couple had been part of those demonstrations. Euphoria had flowed through the city. The communist government quickly fell. However, after a tantalizing and deceptive five days of freedom, the Soviet occupiers returned. This time it was clear they were staying.

The young family made their way through the dark, slick streets to the Western Station (ironically, in Hungarian, the tranquil station) and boarded one of the last westbound trains to Vienna. It stopped about eight miles short of the Austrian border. There the parents bundled their son into a knapsack and handed him his teddy. They gave him some brandy to ensure a nice long sleep and joined two dozen other families for the final miles of their trip, a nighttime walk across the Austro-Hungarian border.

A few weeks and several stops later, the family arrived in the United States. They eventually settled in Los Angeles and began to live the American dream. The father worked in a wallpaper factory by day and went to community college to learn English by night. He earned a B.A., M.A., and Ed.D. at UCLA and became a highly successful educator, eventually running the community colleges of Kansas City and then Los Angeles. The mother, never losing her blond, blue-eyed Hungarian beauty, became the perfect American wife, managing an immaculate home and epitomizing the adage, Behind every successful man, there is an even more successful woman. They gave the child with the teddy bear two siblings, a girl and another boy.

The child with the teddy bear, of course, is me. My familys story, from children of the Holocaust to the flight from Soviet-occupied Eastern Europe, is not unique. In fact, across America you will find many similar stories of refugees and immigrants from almost every corner of the world.

But my familys background shaped the course of my life and, particularly, inspired a vital belief that I hold today: war is to be avoided at all costs, and the key driver of war is not actually religious or political difference; it is economics. Karl Marx was right about one thing. Economics is the foundation of all politics and, as just about every politician knows, the most important economic condition is jobs. Joblessness is the root cause of most of the worst political disasters to have befallen mankind, thus, job creation is the foundation of political stability and a civil society. And I believe there is no better way to create jobs than through entrepreneurship. In fact, for many immigrants, first-generation and beyond, entrepreneurship has been the path to fulfilling the promise of America, the land of opportunity. Entrepreneurship and the American dream are inextricably intertwined.

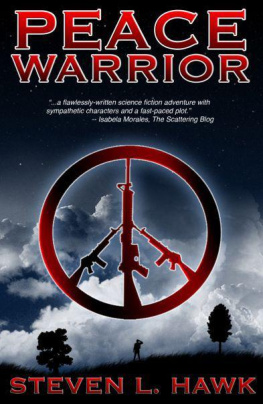

CBS publicity still of the Koltai family for 1957 television program on Hungarian refugees

Back to my family. My father was a voracious reader. Almost everything he read was about World War II. As a child, I could never understand how there could possibly be anything new for him to learn about the war. But he kept reading. When I asked what more he wanted to find out, he would answer, I was in the war, but never understood it. We never understood what was happening outside the blackened windows, what was happening outside the ghetto walls or the concentration camp barracks. Now, I want to know it all. The war, its causes, and its consequences defined what were supposed to be my fathers high school and college years. He never wanted to see such catastrophe happen again.

Indeed, economic failure was, in my opinion, the root cause of the two world wars. Inter-war Germany was economic chaos. While the Weimar era was a great time for culture (see Kurt Weil, Thomas Mann, and the world of cabaret), it was a terrible time to find a job. The Treaty of Versailles that ended World War I saddled the Germans with reparations of some 130 billion gold marks, 400 billion in todays U.S. dollars, with the final installment of $94 million paid only in 2010. The defeated country suffered from mass unemployment and hyperinflation. The German people were buried under a crippled economy, backed into the belief that they had no political choice other than a very strong state that could provide jobs, security, and dignity. This was the poisonous brew from which the Nazi Party could rise to power.

That disastrous rise is what my father and I were trying to understand. What fascinated me most, and what carried real, personal significance, was the key role of institutions in securing economic order and enabling prosperous and civilized societies, in preventing apocalyptic economic collapse and destruction.