Text 2016

University of Alaska Press

Published by

University of Alaska Press

P.O. Box 756240

Fairbanks, AK 99775-6240

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Farrow, Lee A., 1966 author.

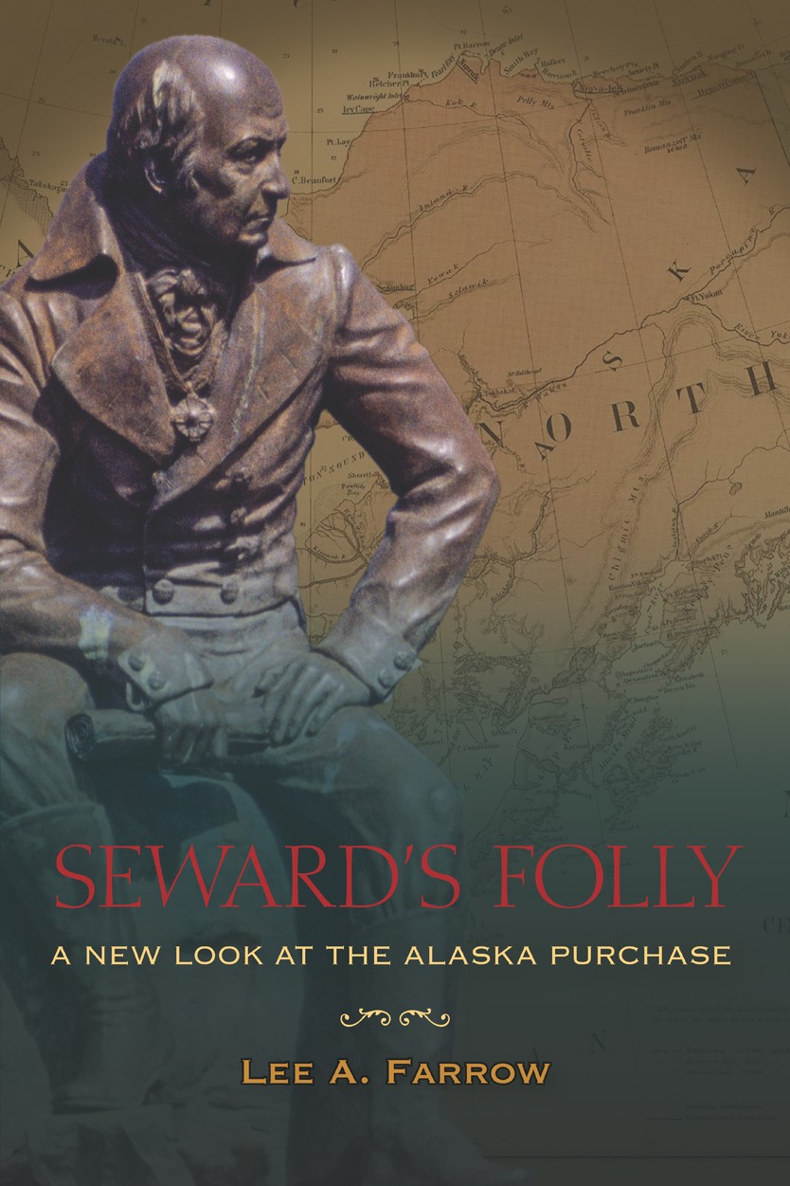

Title: Sewards folly : a new look at the Alaska Purchase / Lee A. Farrow.

Description: Fairbanks : University of Alaska Press, 2016. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016002210 | ISBN 9781602233034 (pbk. : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: AlaskaAnnexation to the United States. | Seward, William H. (William Henry), 18011872. | United StatesForeign relationsRussia. | RussiaForeign relationsUnited States.

Classification: LCC E669 .F38 2016 | DDC 327.73047dc23

LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2016002210

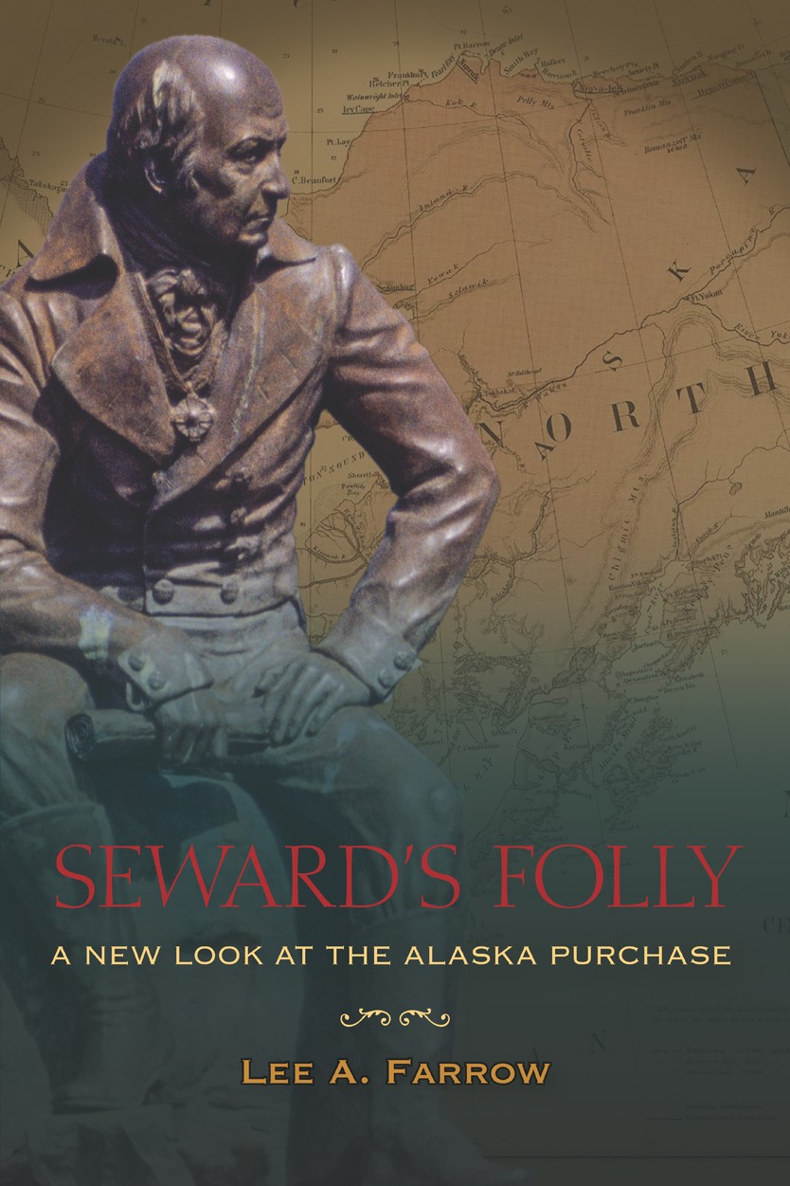

Cover and interior design by Paula Elmes

Cover credits:

Alexander Baranof: Sitka, Alaska. Statue of Alexander Baranof, First Colonial Governor of Russian America, 17901818. Copyright: Charles O. Cecil / Alamy Stock Photo.

Map of Alaska: Public domain. U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey. Created/published Washington, D.C., 1867.

ISBN-13: 978-1-60223-304-1 (electronic)

Acknowledgments

I am very grateful to many people who helped make this project possible. Auburn University at Montgomery provided funding for research at the National Archives and Records Administration through its Faculty-Grant-in-Aid award. The Kennan Institute at the Woodrow Wilson Center covered my expenses to participate in a conference on the history of Russian America in Moscow, allowing me to present some of the material in this book. I thank both of these organizations for their support. I also need to thank the crew at AUMs Interlibrary Loan Department and our new dean, Phill Johnson, who helped me acquire a variety of documents and images. Finally, Heather Adams, a graduate student here at AUM, worked diligently to collect newspaper articles from the period for this research; I greatly appreciate her time and reliability as a research assistant.

I would also like to thank the family and friends who supported me through this process, including, but not limited to, Karen Racine, Heather Thiessen Reily, Angela Mitchell, Dana Bice, and Michael Samerdyke, as well as Neela Banerjee and her daughter, Radha, who gave me a place to sleep in Washington, D.C., on more than one occasion. My parents, husband, and children also deserve thanks for being constant cheerleaders in every new research project.

Introduction

In 1872 Appleton and Companys Hand-Book of American Travel included Alaska for the first time, explaining, Alaska is the newest accession to the territory of the United States, and, though it is not likely to prove very inviting to travelers, a brief sketch seems necessary to complete the Hand-Book. The travel guide went on to say that the popular ignorance about Alaska had produced the most exaggerated claims on both ends of the spectrum, but the guides own assessment of the region was also a mixed bag and did little to promote the likelihood of settlement or tourism. On the one hand, it praised the scenery of waterfalls and icebergs as an inconceivably magnificent sight but then described Sitka as beyond doubt, the dirtiest and most squalid collection of log-houses on the Pacific slope and noted that the governors house was protected from the local Natives by a guard constantly on the alert with rifles loaded, and a field-battery of Parrott guns kept constantly trained on the Indian village, adjoining the town. During roughly the same period, U.S. Treasury Agent H. A. McIntyre sgave another pessimistic evaluation of Alaska and its resources, reporting nor can we look for any material increase of revenue for many years, except in the event of extraordinary circumstances, such as the discovery of so large deposits of valuable minerals as would produce an influx of population.

Appletons guidebook and McIntyres opinion could hardly have been more wrong in their dire predictions of Alaskas future. But one can hardly blame them. In the first years after the purchase, Alaskas enormous size, its geographic diversity, the variations in climate, and the lack of reliable information made it difficult to understand and assess Alaskas full potential. Eventually, gold would be discovered in the Klondike region and a population tidal wave would bring prospectors and settlers from around the globe who would build towns and establish a transportation network to facilitate travel and trade. Much later, Alaska would become famous for its oil reserves. But even in the dark days, before these rich resources had been unearthed, some of Alaskas most spectacular physical features had been discovered and praised by early explorers. Many would echo the sentiments of the geographer Henry Gannett who wrote, Its grandeur is more valuable than the gold or the fish, or the timber, for it will never be exhausted. This value measured by direct returns in money from tourists will be enormous; measured in health and pleasure it will be incalculable. Gannetts prediction was far more accurate than those of Daniel Appleton and McIntyre. Today Alaska is a premier tourist destination, and tourism is an important part of the states economy; between October 2013 and September 2014, nearly two million people visited Alaska, half of them on cruise ships, spending nearly $2 billion while in the state.

The story of how Alaska became one of Americas most valuable treasures begins with a hurried and secret deal in March 1867 that was executed in the dark of night and announced to the American public the following day as a fait accompli. Most Americans know that the United States bought Alaska from Russia for $7.2 million and that there were naysayers and doubters who called the new acquisition the Russian American Folly, Sewards Icebox, or Walrussia. Few, however, are aware of the detailsRussias reasons for selling and Americas reasons for buying, the intricacies of the deal, the complexities of the transfer, the debates and derision in the press and on Capitol Hill, the persistent lawsuit that threatened to ruin the sale, and the scandal that followed. In fact, the story of how Russian America became Alaska is far more interesting and complex than the simple history that most of us were taught.

Russia and the United States both had good reasons to want the sale of Alaska. For Russia, the sale would mean letting go of an unprofitable and hard-to-manage colony, freeing up money and other resources for domestic reform, and pursuing expansion into Russias Far East along the Amur River near China. The United States had other motives. In conjunction with its desire for territorial growth, the purchase of Russian America would accomplish two things: it would expand the United States control on the North American continent, and, many believed, it would eventually lead to the absorption of British Columbia. It also promised to facilitate and expand commercial relations with Asia, making new ports and routes available for the Pacific trade. Though little was known about the true economic value of Alaska at the time, many believed that it would prove to be a profitable acquisition in the end. There were also diplomatic dimensions to the deal. Both countries recognized that this deal would likely trouble Great Britain, but British diplomacy over the previous decades had done little to warm Russian or American hearts. Finally, though the Russian-American friendship was highlighted in diplomatic and media circles in many places, the Alaska purchase was not an act of benevolence between two countries on favorable terms; it was a mutually beneficial deal, carefully negotiated, with very specific aims and aspirations for both parties.