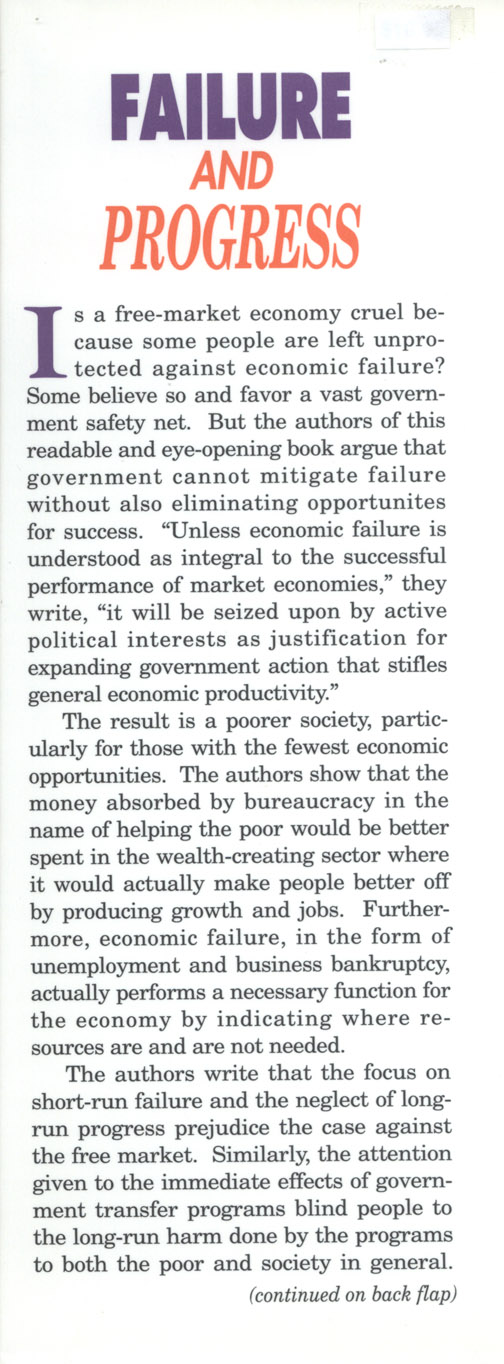

FAILURE

PROGRESS

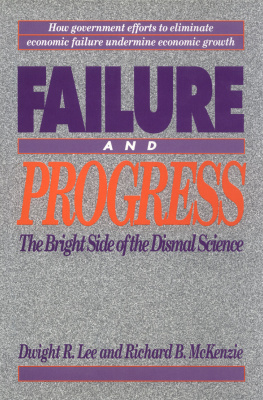

FAILURE

PROGRESS

The Bright Side of the Dismal Science

Dwight R. Lee and Richard B. McKenzie

INSTITUTE

Washington D. C.

Copyright 1993 by the Cato Institute.

All rights reserved.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Lee, Dwight R.

Failure and progress : the bright side of the dismal science / Dwight R. Lee and Richard B. McKenzie.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 1-882577-03-5 : $19.95.-ISBN 1-882577-02-7 : $10.95 (pbk.)

Economic policy. 2. Economic security. I. McKenzie, Richard B. II. Title.

| HD87.L44 | 1993 | 93-16921 |

| 338.9dc20 | CIP |

Cover Design by Colin Moore.

Printed in the United States of America.

C ATO I NSTITUTE

224 Second Street, S.E.

Washington, D.C. 20003

To Betty Tillman

Preface

By any measure of economic success, socialism has been a total failure. The hope of socialism was that it would promote wealth and distribute it fairly by transferring power away from capitalists interested only in profits and giving more control to political representatives concerned with economic growth and social justice. That hope has been dashed. Socialism has succeeded only in providing special privileges to a few by imposing grinding poverty on everyone else.

With socialism a sinking ship, the goal in country after country that has been impoverished by the legacy of Karl Marx is to achieve the wealth-creating power of capitalism. The most dramatic examples of the rejection of socialism and the move to embrace capitalism have come from countries of Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union itself-countries that have experienced the poverty of socialism firsthand. But countries in Africa, South America, and other parts of the world that had been beguiled by the false promises of socialism also are anxious to trade socialism for capitalism.

Although the embrace of the market economy has been widespread, it has also been cautious. Many people want the wealth created by capitalism, but they also perceive the marketplace as being harsh, callous, and unfair. Isn't the market place littered with the victims of those who have suffered the failure of bankruptcy, unemployment, and poverty at the unmerciful hands of market competition? Isn't there some way to accept the wealth that capitalism offers without having to endure the constant failures it imposes? The calls have been for a market economy with a human face or for a third way between the productivity of capitalism and the compassion of socialism. And there is no end to politically inspired proposals to reform the marketplace to protect its innocent victims.

However, contrary to the wishes of persistent critics, capitalism is a bundle of coherent and inextricable attributes. Of course, it would be nice to unbundle the economic package known as capitalism, or the free market, and keep the sweet while rejecting the bitter. It would also be nice if everyone had an above-average income. Unfortunately, the only way to avoid the failures that result from capitalism is to pass up the wealth that results from capitalism. Failures in the marketplace serve an indispensable function in the production of wealth; they provide both information on the most productive use of resources and the motivation for people to respond appropriately to that information. Failures are part of the steering mechanism that directs an economy toward prosperity. Attempting to improve the marketplace by preventing economic failure is equivalent to attempting to improve an automobile by removing the steering wheel. It is no surprise that socialist economies that were applauded initially for eliminating unemployment, bankruptcies, and economic failure of every variety have themselves been colossal economic failures. By allowing economic failures in the small, and converting these failures into useful information, market economies have produced economic success in the large. In economics, overall success depends on a constant supply of small failures.

As economists, we favor the market as the best means for organizing most economic activity. Thus, we believe it is important that the role of economic failure be understood as necessary to the advantages derived from the marketplace. Conveying that message is our overriding objective in this book. There are six important points that are developed and that can be briefly covered here.

First, although economic failure is a positive force in a market economy, it has to be recognized that there is no economy, market or otherwise, that stands apart from the political process. Every economy is a political economy, and for the very reason that economic failure promotes wealth in the marketplace, it also promotes political responses that can undermine the market process. A public understanding of the importance of economic failure is the best way to moderate harmful political responses to that failure. The lack of understanding of the essential role of economic failure stands as the biggest political obstacle to achieving free-market prosperity in formerly socialist countries. The same lack of understanding also prevents the market process from yielding the full measure of its potential wealth in those political economies that are predominantly capitalist.

Second, it is easy to see the failures imposed by the market as isolated occurrences rather than as an integral part of a wealth-creating process. When economic failure is viewed in isolation, it is natural to see it as unnecessarily harsh and unfair and to conclude that government can protect people against such failure' without harming economic productivity. And if government can, at little cost, protect people against failures unfairly imposed upon them by market forces, then surely social justice must require that it do so. But government cannot protect everyone against failure. The best government can do is to protect a privileged few against failure by diminishing the opportunity for success of everyone else. Obviously, such special-interest protection is neither efficient nor fair.

Third, and ironically, for the very reasons that it is both more efficient and fair than alternative economic systems, the market economy appears to be unfair to the superficial observer. The efficiency of the market process derives from the fact that it holds people accountable for the costs of their actions. Those costs are concentrated on market participants in ways that are difficult for them to ignore, and they are commonly imposed through the harshness of bankruptcy, unemployment, and other forms of economic failure. Although this market accountability conveys long-run benefits on all by promoting productivity, each economic interest group prefers to be protected against the accountability of the market while benefiting from the accountability the market is imposing on others. In the marketplace, such free riding on the contribution of others is not allowed, and that is the basis for the fundamental fairness of the market. In the marketplace, all people have to contribute to the general well-being by accepting the failures as well as the successes that come their way. However, because the benefits from market accountability are general, they are easily ignored and taken for granted. Because the costs and failures of market accountability are concentrated, they easily dominate the public's perception of the market and create the impression of unfairness. Indeed, the failures inflicted by the market appear all the more unfair against the backdrop of the economic success made possible by those failures.