BREAKING THE

VICIOUS CIRCLE

THE OLIVER WENDELL HOLMES LECTURES, 1992

The Oliver Wendell Holmes Lectures,

begun in 1941, were established by

the bequest of Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr.,

Harvard Law School Class of 1866.

BREAKING THE

VICIOUS CIRCLE

TOWARD EFFECTIVE

RISK REGULATION

STEPHEN BREYER

HARVARD UNIVERSITY PRESS

CAMBRIDGE, MASSACHUSETTS

LONDON, ENGLAND

Copyright 1993 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Breyer, Stephen G., 1938

Breaking the vicious circle : toward effective risk regulation / Stephen Breyer.

p. cm. (The Oliver Wendell Holmes Lectures ; 1992)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-674-08114-5 (alk. paper) (cloth)

ISBN 0-674-08115-3 (pbk.)

1. ChemicalsLaw and legislationUnited States. 2. CarcinogensSafety regulationsUnited States. 3. Health risk assessmentUnited States. I. Title. II. Series.

KF3958.B74 1993

353.0082323dc20

92-38934

CIP

To Joanna

CONTENTS

This book is about federal regulation of substances that create health risks. We read almost daily about chemicals that threaten our air, our water, our livesasbestos, benzene, PCBs, EDB, Agent Orange, Alar, and many others. We hear charges and countercharges: callous industry, greedy lawyers, lives unnecessarily lost, billions of dollars wasted in a pointless search for perfect safety. Were Milton alive, he might describe our present regulatory system as one where Chaos umpire sits, and by decision more embroils the fray by which he reigns.

How should government deal with such problems? Which substances should we regulate? In what order? To what extent? Who should decide, and how? I shall approach these questions not as a scientist, or an economist, or a regulator, or a member of the public, but as a lawyer interested in the design of governmental institutions. , an institutional analysis, draws connections between problems, causes, and potential institutional solutions.

There is a subtext in this book, a subtext that seeks to respond to Oliver Wendell Holmess admonition to look for the general in the particular. The book suggests a general form of analysisof underlying substance, political causes, and institutional solutionsthat may apply to other public policy problems. I also hope that the book will encourage students of the law to become interested in the general kind of public policy problem I describe, a problem that combines substance, procedure, politics, and administration. Lawyers trying to help create better institutional solutions to important social problems need not simply reason deductively from first principles of procedural fairness or democratic theory. Rather, they can impose those principles as proper constraints, within which they work toward the Platonic goal of every institutionuniting political power with wisdomso as better to resolve the human problems of our times.

This book, more than most, owes its virtues to the help of many others, who were generous with time, information, and commentary. Let me mention a few of them: members of the Carnegie Commission Task Force on Science and Technology, including its chair, Helene Kaplan, as well as Alvin Alm, Richard Ayres, Douglas Costle, E. Donald Elliott, Richard Merrill, Gil Omenn, Irving Shapiro, and Patricia Wald, and staff members Jonathan Bender, Steven Gallagher, David Robinson, and Mark Schaefer; my colleagues at Harvard, Charles Fried, John Graham, Phil Heymann, and Richard Zeckhauser; scientific and regulatory experts, among them Richard Belzer, Devra Lee Davis, Adam Finkel, Richard Li, Charles Powers, and Richard Stewart; research assistants and helpers, including Kate Adams, Henk Brands, Robert Brauneis, Susan Davies, Jacques deLisle, Simon Frankel, Jeff Lange, Elizabeth Moreno, Aaron Rappaport, Kim Rucker, Simon Steel, and Michael Wynne; and my editor, Michael Aronson.

Regulators try to make our lives safer by eliminating or reducing our exposure to certain potentially risky substances or even persons (unsafe food additives, dangerous chemicals, unqualified doctors). When the regulator focuses upon reducing exposure to a particular substance, when the risk is to health, when the risk is fairly small or uncertain, the regulator typically uses a particular systema heartland regulatory system, the common features of which underlie many different statutory programs.

I focus upon this heartland system, using as an example the regulatory effort to reduce exposure to cancer-causing substances, both because of its illustrative power and because the publics fear of cancer currently drives the system. Still, much of what I say about cancer and similar health risks has broader application to other regulatory screening efforts, for example, whether or not to require seat belts for infants in airplanes, or how to regulate swimming-pool slides.

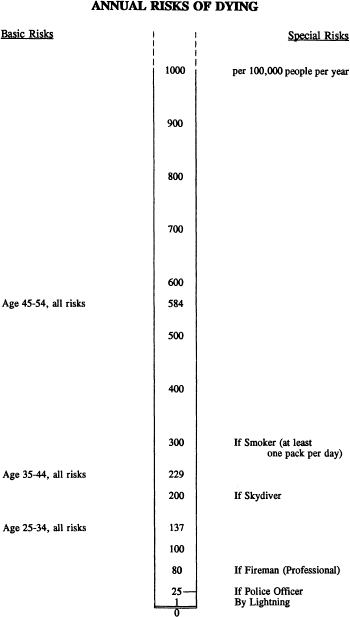

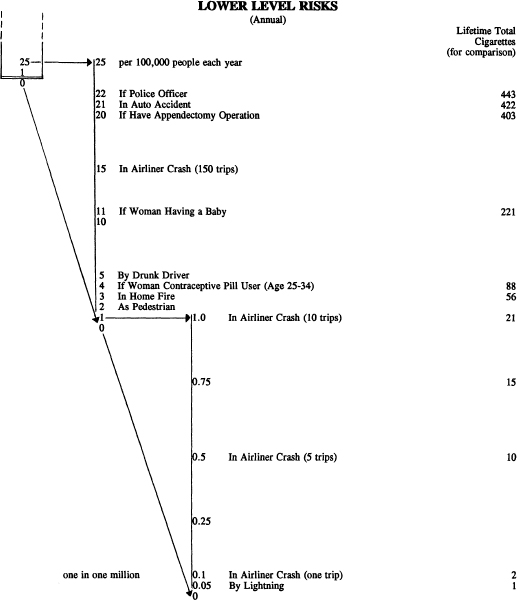

You need four pieces of background information. First, you need some idea of what I mean by small risk, the subject of many regulatory programs. The best device I have found for explaining the term is the risk ladder prepared by Robert Cameron Mitchell, of Clark University (

About 2.2 million persons die each year in the United States, out of a population of 250 million. Knowing nothing about an individual person, one can assess a crude individual risk of death as just under 1 in 100, or 1,000 out of 100,000, as shown at the very top of the figure. If one knows a persons age, one can make a more refined assessment, such as 137 out of 100,000 for all persons between 25 and 34. Certain individuals incur special risks of death because of their professions or their activities. A skydiver, for example, incurs a special annual risk of 200 in 100,000. Those special risks are shown at the right. The enlarged segment of the bottom of the ladder shows special small risks such as the risk of being killed by a drunk driver (5 in 100,000) or being hit by lightning (1 in 2,000,000).

Figure 1. Risk ladder showing annual death rates for basic and special risks.

Source: Robert Cameron Mitchell, Clark University.

Most people want to ask, One in a millionis that a lot or a little? There is no good answer to that question. If one focuses upon statistics, it may seem very little; if one tries to focus upon the 250 or so individual deaths that this number implies (in a population of 250 million), it may seem like a lot. Mitchell, who is an expert in trying to communicate this kind of information neutrally (he employs this chart to help elicit public reactions), uses a cigarette equivalency table, shown at the right of the lower-level risk ladder. It indicates that the risk of being hit by lightning is the same as the risk of death from smoking one cigarette once in your life, and it grades other risks accordingly. For present purposes, you should keep in mind that many of the regulatory risks at issue here are in the blown-up small-risk portion of the ladder.

Second, you should know a few facts about cancer, the engine that drives much of health risk regulation. Of the 2.2 million Americans who die each year, about 22 percent, or 500,000, die of cancer. In other words, the number of people who die each year from types of cancer whose incidence seems likely to be reduced by regulation is below an estimated ceiling that itself varies between 10,000 and 50,000; it is probably less than 2 percent to 10 percent of all cancer deaths; it is 7 percent to 33 percent of deaths associated with smoking. The numbers must range from less than 1 percent to less than about 3 percent of our 2.2 million annual mortality total.