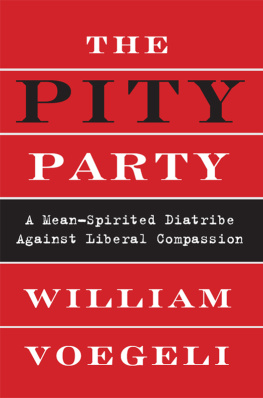

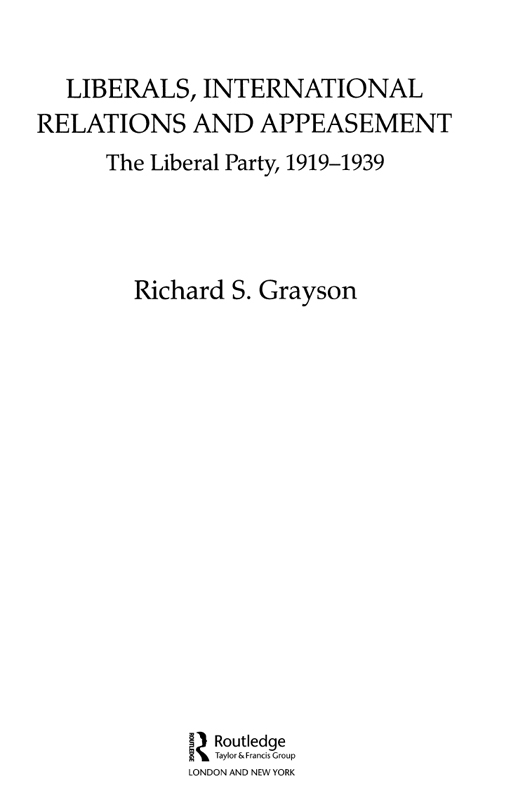

LIBERALS, INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS AND APPEASEMENT

ROUTLEDGE SERIES: BRITISH FOREIGN AND COLONIAL POLICY

ISSN: 1467-5013

Series Editor: Peter Catterall

This series provides insights into both the background influences on and the course of policymaking towards Britains extensive overseas interests during the past 200 years.

Whitehall and the Suez Crisis, Saul Kelly and Anthony Gorst (eds)

Liberals, International Relations and Appeasement: The Liberal Party; 1919-1939, Richard S. Grayson

Britain and the Empire-Commonwealth, 1945-1963: A Metropolitan Perspective, Frank Heinlein

First published in 2001 in Great Britain by

Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RN

270 Madison Ave, New York NY 10016

Transferred to Digital Printing 2007

Website: www.routledge.com

Copyright 2001 Richard S. Grayson

The right of Richard S. Grayson to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Grayson, Richard S., 1969

Liberals, international relations and appeasement: the Liberal Party, 19191939. (British foreign and colonial policy)

1. Liberal Party History 20th century 2. Great Britain Politics and government 19101936 3. Great Britain Politics and government 19361945 4. Great Britain Foreign relations 19101936 5. Great Britain Foreign relations 19361945

I. Title

ISBN 0-7146-5092-7 (cloth)

ISBN 0-7146-8133-4 (paper)

ISSN 1467-5013

ISBN 978-1-135-27097-1 (epub)

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Grayson, Richard S., 1969

Liberals, international relations, and appeasement: the Liberal Party, 19191939/Richard Grayson.

p. cm. (Roudedge series: British foreign and colonial policy, ISSN 1467-5013)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-7146-5092-7 (cloth) ISBN 0-7146-8133-4 (paper)

1. Great BritainPolitics and government19101936. 2. Great BritainPolitics and government19361945. 3. Liberal Party (Great BritainHistory20th century. 4. LiberalismGreat BritainHistory20th century. 5. Great BritainForeign relations19101936. 6. Great BritainForeign relations19361945. 7. Great BritainForeign relationsGermany. I. Title. II. Roudedge seriesBritish politics and society.

DA578 .G73 2001

324.24106'09'042dc21

2001032493

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher of this book.

Typeset in 10.5/12.5 Zapf Calligraphic by Vitaset, Paddock Wood, Kent

Cover illustration: The Liberal Party 1929 general election leaflet.

Source: Reproduced courtesy of University of Bristol Library.

Publishers Note

The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality of this reprint but points out that some imperfections in the original may be apparent

Printed and bound by CPI Antony Rowe, Eastbourne

Contents

Series Editors Preface

F OREIGN POLICYMAKING in opposition is never easy. There is not only the obvious problem that, at some point, wider loyalties are likely to constrain oppositions, but also the question of what is the purpose of policymaking in opposition anyway? This is a particular problem for a dwindling minority party, as the Liberals were in the process of becoming in the years covered by this book. Their moments of influence during the inter-war years the two minority Labour governments of 1924 and 192931 and the initial phase of the National Government in 193132 were brief and problematic. In such circumstances, Liberals could not hope directly to shape policy. Despite holding the balance in the Commons in 1924, for instance, they nevertheless could do little more than oppose the naval estimates. Rather, Liberals had to seek to shape the environment in which policy was made and to promote particular principles from which policy might be elaborated.

In some ways, the climate of the period was not inimical to this endeavour. Liberalism survived as an ethos, if not as a political programme. Moreover, it furnished an electoral battlefield which both the major parties sought to colonise. It could not be ignored. Indeed, at the start of the period, objectives and institutions peculiarly associated with the Liberal Party, such as free trade, to a declining extent, and the newly established League of Nations, enjoyed a status almost as political shibboleths, although in both cases the situation was to change rapidly in the 1930s. Even then, however, the idea of collective security through the League retained the potency to shape the way in which the National Government approached the 1935 election. Liberal ideas on international affairs, in other words, enjoyed a constituency well beyond the formal boundaries of the party.

These ideas, Richard Grayson demonstrates, had a number of key components. Central to these was the importance of international cooperation. Both the League of Nations and free trade, in their different ways, were seen as devices to promote this. Whilst nation states were seen as necessary expressions of community, policies to limit their absolute sovereignty were seen, not least in the light of the carnage of the First World War and the flawed peace that followed, as eminently desirable. The key concept, as Grayson shows, was that of interdependency, the expression in the international arena of the utilitarian object of securing the good of each through the good of the whole. The Empire, for instance, was seen throughout this period by most Liberals as a force for good in which this principle was realised.

How interdependency was to be achieved elsewhere during these years was, however, more problematic. In the 1920s, the League of Nations was too readily seen as sufficient. During the following decade, in contrast, most Liberals turned to ideas of collective security and international police action. These were rejected by others, notably Lord Lothian, as incompatible with the ideas of interdependency for which Liberals stood rather, they seemed to threaten a return to the dangers of the pre-1914 alliance system. He was of course right, in a sense, but for the concept of interdependency to work a sense of mutual benefits, equity and easy redress was required, none of which factors, as Keynes warned, was secured by the post-1918 settlement. By the 1930s, it was too late. Liberals instead had to join with the other parties in groping towards responses to the international storm clouds of the decade.

In this the Liberals seem to have occupied a middle position: more belligerent than the government in the face of aggression, and more prepared than Labour to support increased arms spending. Their position, however, only shifted slowly and was not fully apparent until the end of the decade. For instance, as Grayson points out, until 1938 they continued to favour non-intervention in Spain; not, admittedly, on the same grounds as the government, but because they were unconvinced that intervention in a civil war was consistent with Liberalism. The relationship between interdependency and the projection of power was no less of a problem. Collective security, ultimately, required the latter, even if an attempt was made to keep with the earlier faith by reference to tempering it by recognition of the just grievances of the aggressor powers. Realising this in practice is, however, never an easy balancing act.