Preface

Imagine that a very large oil painting, a triptych, has recently been discovered. Each of the panels is badly soiled; still, the painting seems recognizable. It is oddly evocative of John Gasts 1872 composition, the allegorical American Progress. Among the discernible images in the first panel are Harry Truman and Joseph Stalin at Potsdam and John Foster Dulles refusing to shake Zhou Enlais hand at Geneva in 1954; in the second one, John Kennedy gives his inaugural address and Lyndon Johnson agonizes over Vietnam; a discarded placard proclaiming the Year of Europe and Richard Nixon boarding a helicopter on the White House lawn adorn the third panel. The painting has to be a rendition of the history of the Cold War through August 1974.

Cleaning and restoration of the triptych reveal a much different story. In the lower left of the first panel sits Henry Luce penning his essay The American Century. Visible along the lower border of each panel are crowds of young people from various locales, some carrying signs of protest. Across the top reside symbols of Americas vast material and cultural prowess: a television set, an automobile, an airplane, a movie camera, a trumpet, and more. Present now in the first panel are more people of color than were previously visible; in the second one, gold bars with wings fly out from Fort Knox; the third panel also shows Japans copious export trade and Chiles presidential palace, La Moneda, in flames.

What to make of this transformed canvas? It could simply be a more complete depiction of the highly familiar tale of the Cold War. Or is something else influencing the brushstrokes of our nameless artist? If context matters, then Luces presence holds the key. The refurbished images on the triptych should be seen as coming under its sway, their story still to be told.

The germ of an idea for a book akin to this one originated, inchoately to be sure, in 1969 when I was an MA student at Ohio State University. Also at OSU then was the now-superb historian Melvyn P. Leffler. Mel and I and a small number of others spent hours talking about American history, especially the origins of the Cold War, and we speculated endlessly about what the Cold War meant for understanding Americas place in the modern world. These latter discussions came to mind when I decided to write this book.

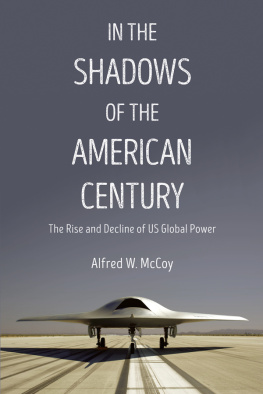

The Rise and Decline of the American Century describes and analyzes what I consider the active lifespan of the American Century as the noted publisher Henry R. Luce conceived it in 1941. Luce very much wanted the United States to seize the reins of global leadership, to exert supremacy over international political and economic affairs. U.S. officials, commencing in 1945, endeavored to spread Luces vision as widely as possible. I contend that the American Century developed alongside the Cold War yet was a far grander projectone designed to establish the United States as the worlds hegemon in strategic, political, and economic realms. To succeed in that effort entailed fostering thoroughgoing change in what became known as the Free World. Hegemony was inconceivable without widespread acceptance of Washingtons leadership; in turn, leadership depended both on consultation with allies and client states and on the credibility of U.S. actions throughout what I call the free-world society.

Waging cold war became an integral aspect of the Lucian project. Policymakers from the Truman through the Johnson administrations internalized Luces vision and were determined to give it practical effect. That effort collapsed by the end of 1968 largely because of the Vietnam War, burgeoning economic troubles that a weakened dollar exemplified, and a general lack of receptivity to U.S. hegemony beyond Western Europe and Japan, most notably in the Americas. Officials rightly worried that if the American Century were not embraced by people and nations close to home, then a positive reception elsewhere was far less likely. Thereafter, Richard Nixon and Henry Kissinger turned to dtente in an attempt to chart a path to primacya way to exert power and influencein world affairs; they came up short. More than four decades later, it is worth considering whether the very idea of the American Century has over time become little more than a useful shibboleth. I think not, if only because those who wanted to give it life did bring the American Century into being and then undertook to nurture it for two decades.

My goal in writing this book is in its way nearly as ambitious as that of those who forged the American Century. I want readers to know at the outset that this is not another book about the Cold War. Instead, I seek to revise how we think about U.S. foreign relations from the final months of Franklin Roosevelts presidency through Nixons resignation in August 1974. To do so, I scrutinize in greater depth some of the ideas that I developed in the cold-war sections of my book National Security and Core Values in American History (2009). Two prominent histories of that eraJohn Lewis Gaddis, The Cold War: A New History (2005), and Campbell Craig and Fredrik Logevall, Americas Cold War: The Politics of Insecurity (2009)do not mention the American Century; Craig and Logevall accord Luce only a cameo role. These books confine themselves to narratives placing superpower relations and American politics, respectively, at the heart of their stories.

A secondary, yet essential part of my undertaking is recognition of the role of emotions, most especially fear and anxiety, in the making of U.S. foreign policy. Fear, which I explored at some length in my 2009 book, had a profound impact on threat perception and decision-making and influenced how the United States engaged the world through 1968 as authorities strove to implant abroad the American Century. Fear in dealing with adversaries, whether well founded or self-induced, often seemed near at hand because of the assumption that foes like the Soviet Union and China were inherently ill disposed toward Washingtons objectives. Policymakers also worriedsometimes unduly, sometimes notthat the interests of friends and allies, notably in Western Europe and East Asia, might not align with those of the United States in a given situation, which would challenge Americas claims to leadership.

Without making a study of emotion central to the core of my story, as Frank Costigliola, for example, has done in his several influential writings about George F. Kennan, I nevertheless purposefully chose to use the verbs feared and worried on numerous occasions in the first six chapters. U.S. officials were obsessively concerned that what Luce called the opportunity for leadership was eluding themhence my choice of words. Less emotionally laden alternatives, like thought or believed, among others, I employ as appropriate.

The present study is at once original and synthetic. The narrative and thematic structure springs from my years of teaching about the United States in the world. Research relies on the State Departments published documentary volumes, Foreign Relations of the United States, and the myriad of online primary documents. Online sources include records on the economy and finance from the Public Record Office in Great Britain, documentary compilations of the Cold War International History Project of the Wilson Center and the National Security Archive, declassified documents released by the Central Intelligence Agency and the State Department (some readily accessible through presidential libraries), and oral histories from presidential libraries and other collections.