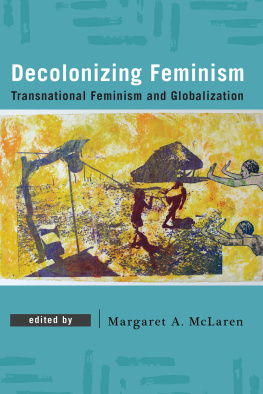

As with any piece of academic writing, this book reflects its author and where she stands in the context of social, institutional and geopolitical relations. As such, Decolonizing Geography: An Introduction is deeply situated and is not about decolonizing everywhere. It emerges principally out of Anglophone postcolonial and decolonial geography and Anglophone geographers critical engagements with numerous Other geographies and knowledges around the world. As such, the book speaks back to the global predominance of Anglophone geography in former colonial and settler colonial countries where racialization, the westernizing university and settler colonialism operate and are challenged. Brazilian, Mexican, French and Hungarian geographies, to name a few, have different stories to tell. I encourage all readers to think about this book in tandem with the local and regional decolonizing discussions where they live and work.

My position in these geopolitical and intersectional configurations is as a white, cis-gender woman with an Anglo name in an overwhelmingly white British department of geography. My training and experience are in human geography; the department includes human and physical geographers, the vast majority white, especially among faculty. Geographers of colour have argued rightly that geographys urgent task of decolonizing must not rest solely on racialized minorities. I concur wholeheartedly, and as a white ally stress the importance of white geographers informing themselves about decolonizing and anti-racism. The construction of a decolonial pluri-geo-graphy or a world of many worlds depends on all of us. Plural decolonizing geographies crucially require white geographers to take responsibility for and actively work to overturn racialized exclusions and assumptions. The knowledge geopolitics behind this book additionally reflect my decades of ethnographic work with Latin American scholars, activists and communities, especially in Andean rural districts and with Indigenous groups, leaders and organizations. It is their critiques, experiences of racism and exclusion, and hopeful agendas for change that enliven this book. In terms of its focus, however, the book is written to be accessible and relevant for physical as much as human geographers. The chapters include physical and human geography examples, discussions, and pointers to further reading. The book was also influenced by events during the Covid-19 pandemic which provided daily reminders of colonialitys persistence and of decolonizing ripostes such as the Black Lives Matter movement.

The book aims to broaden understanding of why decolonizing matters among instructors and students in geography and cognate disciplines. covers research of various kinds, including short student projects. To make the decolonizing framework and approach more accessible, a Glossary at the end of the book provides definitions of terms used in the book. North American, European and Australasian geographies appear throughout, although their tertiary education systems and terminologies vary. I have tried to avoid too many British-isms! Across these regions, geographers differ in whether and how they self-identify in racial-ethnic and territorial terms; I provide this information where available but cannot do so consistently. This book addresses exciting and rapidly moving debates which shift as activism and scholarship consider important dimensions related to colonialism. This context emphasizes the urgency for geography and geographers to change their approaches, materially and on short time scales. So, while reading this book, I encourage readers to put it into conversation with blogs, non-academic writings, activism and news stories that speak to decolonizing issues where you stand. Finally, in an introductory textbook it was inappropriate to address structural issues connected to neoliberal colonial academia that systematically influence hiring decisions, promotions, funding streams for research and the colonial biases of journals and peer review. These are crucial issues rightly critiqued in other forums.

To acknowledge the support, encouragement and care that made this book possible, I end with some thanks. Thanks to Pascal Porcheron, Stephanie Homer and Ellen MacDonald-Kramer at Polity, who encouraged and cajoled this manuscript to the end, in the nicest ways. I have tried to unlearn ingrained assumptions, so Im extremely grateful to everyone who pulls me up on partial understandings and privileged blind spots. Key among those who did that are three anonymous readers. Incorporating their suggestions, together with bibliographies and insights into unfamiliar contexts, the book aims to do justice to those plural realities, albeit humbly and provisionally. Friends and colleagues near and far inspired me with writing, action and conversation during the books conception and writing: a big thank you to Laurie Denyer Willis, Rogerio Haesbaert, Humeira Iqtidar, Anna Laing, Sian Lazar, Monica Moreno Figueroa, Kamal Munir, Nancy Postero, Isabella Radhuber, Catherine Souch, Natasha Tanna, Yvonne Underhill-Sem, Georgie Wemyss and Sofia Zaragocn. I am very grateful to Nicola J. Thomas and Ian Cook for sharing teaching materials and reading a draft chapter. Debates at the Decolonial Research Lab sharpened my thinking; gracias to Tiffany Dang, Ellen Gordon, Ana Guasco, Sam Halvorsen, Laura Loyola-Hernandez, Tami Okamoto, Sandra Rodriguez Castaeda and Giulia Torino. Current postgraduate students Matipa Mukondiwa, Emiliano Cabrera Rocha, Ashley Masing and Lily Rubino bring news and plural perspectives to my attention over Zoom. Over the years, final-year students on the geographies of postcolonialism and decoloniality course have prompted me with questions; I hope this text does them justice. The Decolonizing Cambridge Geography working group especially Sophie Thorpe, Sophia Georgescu, Fran Rigg, Joseph Martinez-Salinas, Josie Chambers, Ollie Banks, Charlotte Millbank, Ed Kiely and Fleur Nash devised an agenda for departmental change where I work. Taking that agenda to the next level would not have been possible without steady support from Bhaskar Vira, Harriet Allen, Charlotte Lemanski, Michael Bravo, Sam Saville and Phil Howell, among others. Over longer stretches of time and distance, the experiences and voices of Ecuadorian Kichwa warmikuna and Tschila sonala continue to resonate through my thinking and acting on decoloniality; for that, I honour their strength in facing down numerous hurdles, and appreciate their generosity in dialoguing with me. And for my whole family, including a 2021 baby, a thousand thanks for many thousands of moments of love and care.