First published by Haus Publishing in 2021

4 Cinnamon Row

London SW11 3TW

www.hauspublishing.com

Copyright Jack Brown, 2021

The right of the author to be identified as the author

of this work has been asserted in accordance with

the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

A CIP catalogue record for this book is

available from the British Library

Print ISBN: 978-1-913368-14-2

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-913368-15-9

Typeset in Garamond by MacGuru Ltd

Printed in Czech Republic

All rights reserved

Preface

Why, Sir, you find no man, at all intellectual, who is willing to leave London. No, Sir, when a man is tired of London, he is tired of life; for there is in London all that life can afford.

Samuel Johnson, 1777

You guys should get out of London. Go and talk to people who are not rich remainers.

Dominic Cummings, chief adviser to the prime minister, 2019

The London problem

It is now approaching 200 years since William Cobbett, radical pamphleteer and advocate for rural England, famously described London as the Great Wen, an ever-expanding and ugly cyst sucking the lifeblood of its nation. But recent years have seen national politicians return to this theme, describing London as the dark star

The more things change, it seems, the more they stay the same. The economic gap between capital and country grows ever larger, and Londons powerful draw continues to cause concern. But todays anti-London sentiment has acquired additional new strands: political, economic, historical, and cultural. Some are based on legitimate grievances and concerns, others on prejudice and misconceptions. All have become interwoven sometimes deliberately, sometimes accidentally into a complex knot of resentment against the capital.

This book attempts to untangle some of these strands, however briefly, to try to better understand them. It begins with an overview of the facts, before undertaking a historical review of past attempts to address Londons perceived dominance within the UK. Next, it explores public perceptions and the relationship between rhetoric and reality. In closing, it considers the impact of the coronavirus pandemic, which arrived between this books conception and its delivery, and some possibilities for the future.

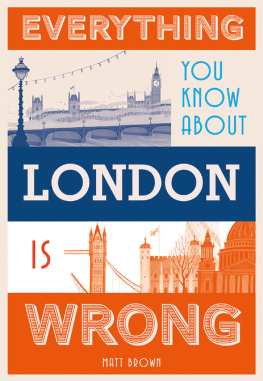

This book

This addition to Hauss Curiosities series draws heavily on my research for a report entitled London, UK, conducted in 2018 for Centre for London. I am extremely grateful to Centre for London for the opportunity to spend time getting to know this subject and for its support particularly that of Richard Brown (no relation). The views expressed in this book, however, are very much the authors own.

In this book, I have identified several threads of anti-London sentiment that interweave, overlap, and are often incorrectly identified or mistaken for one another. This, to some extent, is the problem.

London means different things to different people. It has become a catch-all word for whatever it is that people dont like, from government to globalisation and much more besides. I have attempted to deal with several (if not all) of these interpretations of London, but I too make the mistake of flicking between different meanings and conceptualisations political, economic, and cultural of what is, ultimately, a place populated by people. These 9 million or so people are all very different to one another, as are their 57 million fellow Brits. Sometimes it is useful to observe certain traits and place these people into various groups, but as individuals they defy stereotypes as often as they fit them.

London itself is so large and multifaceted that it is tempting to cherry-pick facts and ignore others for the sake of building an argument for or against the city and its people. No doubt I am as guilty as others in doing this, but I have tried to be balanced and accept nuance. Ultimately, we must accept that this is one point of view. Others are available. (But mine just to be clear is the right one.)

Personal note

On that note, I must include a disclaimer. I am a life-long north-east Londoner. I am a somewhere person, and I have lived in one London borough my entire life. I feel a strong attachment to my place. My football team, through my family, is Arsenal. People around the world support Arsenal, but I think that my connection to the club is real; theirs is just a hobby. They could have picked any team. I couldnt.

This is how I feel about London, or at least my patch of north-east London. But this is clearly not true (nor, for that matter, is it really true of football clubs). Friends and family have moved, generally outwards, whether to find more space, a change of lifestyle, or a better standard of living. Others have moved in. I could move too. I dont own this place, and it is changing rapidly even in front of my eyes. Parts are almost unrecognisable to me, already, at the age of thirty-four. Yet still I cling on to this patch of land.

It has a lot going for it. And I have been very fortunate to be able to stay here as the place has changed around me. At times, it can feel like I am running to stand still as prices and properties (and property prices) grow ever upwards and new shops pop up left, right, and centre, selling beard oil and bacon jam. It would help me, as a Londoner, if the capitals magnetic attraction to people, money, and opportunity were to cool down a little bit. But I am still here. I realise how fortunate that makes me I have moved up in the world at just about the right pace, or at least close enough, to be able to stay put. But I am a Londoner, and this place is my home. When I read lazy stereotypes and criticisms of London and Londoners, I cannot help but take it personally.

All of which makes it very hard to write a calm, balanced response to this issue; I have attempted to do so nonetheless.

1

People and Place

Before we attempt to unravel the many different threads of historical and contemporary anti-London sentiment, we must first understand what London and Londoners really are. Both the citys people and the place itself are often stereotyped, misunderstood, and misrepresented, both wilfully and accidentally. While the reality is of course complex and multifaceted, a little more understanding about the capital itself from its historical origins to its place in the UK economy today is important. So, too, is an understanding of the much-maligned people who live there.

Londoners

At the start of 2020, before the coronavirus pandemic, London was home to nine million people, and this figure was expected only to increase. Londons growth has been driven primarily by natural change (births exceeding deaths), but also by new arrivals from overseas. In terms

Todays Londoners are also incredibly diverse, in every sense of the word. Over a third were born abroad, which is more than double the UK-wide proportion. London looks, and sounds, different to the rest of the UK. But then, parts of London also look and sound entirely different to one another.