First published 2005 by Ashgate Publishing

Published 2016 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 2005 George Lawson

George Lawson has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as the author of this work.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Lawson, George

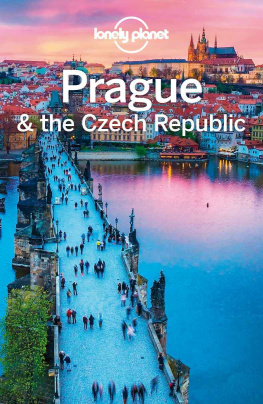

Negotiated revolutions : the Czech Republic, South Africa

and Chile

1. Revolutions 2. Revolutions - Case studies 3. Negotiation

Political aspects 4. Negotiation - Political aspects - Case

studies

I. Title

321.094

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Lawson, George, 1972

Negotiated revolutions : the Czech Republic, South Africa and Chile / by George

Lawson.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-7546-4327-1

1. Revolutions--Social aspects. 2. Revolutions--Czech Republic. 3. Revolutions--South Africa. 4. Revolutions--Chile. 5. Social history--20th century. 6. Historical sociology. I. Title.

HM876.L39 2005

303.64--dc22

2004020209

ISBN 9780754643272 (hbk)

The veteran British reporter Mark Tully entitles one of his many books, No full stop in India.1 Tullys title conveys the idea that the history of his adopted country is one which is at once so complex and so rich, that it defies a finale or a neat conclusion. I think that the same can be said for any of the worlds countries: all states are works in motion. Revolutions are perhaps the most powerful gauges of this world of perpetual movement, attempts as they are to renew domestic orders and influence the wider flows of international politics. Although revolutionary states usually fail to achieve this double aim, they stand as captivating insights into the complex meanderings of world history.

If revolutions are incomplete, so too is any attempt at studying them. As such, this book does not attempt to find a point of final closure; it is less concerned with dates and snap-shot images of particular societies than with the dynamics of change that revolutions evoke across time and place, both to the domestic societies within which they take place and the wider international relations that they effect. I hope that, by concentrating on what is necessarily a moving picture, it will be possible to draw out some patterns that move beyond the level of thick description, patterns that tell us something about the pace and direction of world historical change, yet which retain a sensitivity to the experience of each, unending narrative.

Like revolutions, this book has been long in the making. The choice of case-studies was, in part, informed by my political awakening as a young student during a period in which the Pinochet regime was ousted, the Berlin Wall came down and apartheid was abandoned. Interesting times indeed. As an undergraduate at Manchester University, I studied the international dimensions of these changes, mostly under the watchful eye of Inderjeet Parmar. This was followed by periods of further study at the London School of Economics, when this book first began to take shape. However, it was only during my time at the London based think-tank, Demos, that the seeds of this project began to fully develop. At Demos, I learned, really for the first time, how to gather and assess large amounts of material, how to think critically and how to write without sending readers into paroxysms of laughter or despair. In this Herculanean task, particular thanks are reserved for Geoff Mulgan, Tom Bentley and Mark Leonard.

The book took a more concrete shape during a subsequent spell in the Department of International Relations at LSE. This research was sustained by two ESRC grants: numbers R00429934266 and PTA-26-27-0459. I must thank both the ESRC for providing such generous grants, and also my mother, Annette Lawson, who took responsibility for administering the first grant application while I completed the necessary forms in cyber-cafes dotted around Chile. As ever, she performed this task with outstanding diligence and care.

The principal source of inspiration behind the academic content of this book is Fred Halliday. Freds detailed and insightful comments have improved the work no end, while his range of contacts and unwavering commitment to the project have been hugely beneficial to the final product. Standing alongside Fred in terms of academic influence is the former convenor of the LSEs International Relations Department, Margot Light. Margot has been an impeccable surrogate intellectual mentor, providing indispensable advice into how to make the book both more interesting and more rigorous. Margot put me in touch with Otto Pick, who set up a range of interviews in Prague it would be difficult to better. Raymond Suttner and Terry Oakley-Smith acted as prolocutors par excellence to South Africas complex society.

During the course of completing the book, I have accumulated numerous other debts. Particular thanks are reserved for those friends and colleagues who have read part of all of the book, improving it considerably along the way. Most notably, Margot Levy, a family friend, editor and indexer extraordinaire, invested a huge amount of time and effort in improving the professionalism of the finished product. I have not yet found a way to thank her sufficiently for this work, but hope that the study reflects at least some of the passion Margot has exhibited towards it. My father, David Lawson, read the entire manuscript and improved the language, coherence and structure of the argument to great effect. Special thanks are also reserved for Colin Bundy, Arne Westad, John Hobson, Justin Rosenberg, David Armstrong, Harry Bauer, Kim Hutchings and Brian Belle-Fortune. Jennifer Chapa and Barry Kavanagh provided logistical support and helped to revise the bibliography. Kirstin Howgate, Pam Bertram and other members of the Ashgate editorial team have been meticulous and supportive publishers.

As it has developed, so the argument of the book has become clearer, not least because of stringent examination by students on the MSc International Politics at LSE. Students on this course are consistently hectored about the need to thoroughly trace the roots of contemporary debates, to look sideways at debates taking place in parallel disciplines, and to back up their arguments with examples: three principles I have tried to adhere to in this study. No doubt, these students, past and present, will be the first to tell me whether I have succeeded. The book is not intended to be an introductory textbook, but neither is it aimed above the heads of undergraduates and postgraduates. It is, reflecting my own journey, explicitly interdisciplinary, written from a perspective at the crossroads between International Relations, sociology and history. To help readability, I have adopted the Harvard style, but in footnotes rather than in the main body of the text. Non-academic articles and electronic sources can be found in these footnotes: the rest of the material referred to is contained in the fairly extensive bibliography. Following convention, I use upper case IR to delineate the subject of International Relations and lower case, international relations, when dealing with its practice.