Foreword

Ana Avendao

The case studies collected in Mobilizing against Inequality expertly explore what is increasingly apparent to scholars, labor activists, and workers: traditional models of worker representation that have allowed workers to win a greater share of productivity and a political voice are failing to adapt to a changing economic and political environment. In recent decades, corporate-funded politicians have pushed trade liberalization, privatization, and austerity. Employers have shifted traditional employment relationships and informalized workers through subcontracting, privatization, or some other form of intermediary contracting arrangement in order to reduce labor costs and avoid regulations associated with formal employment. Workers share of national income is in decline worldwide, in tandem with union density. Only 7 percent of the worlds formal economy is organized into free and independent trade unions. With a sharp decline in union density and collective bargaining coverage, inequality has increased dramatically and threatens global growth and stability.

In the Global North, perhaps nowhere are these trends more clearly illustrated than in the expansion of low-wage workplaces, many of which employ a majority immigrant workforce. With globalization, many workers have seen their local economies devastated and been forced to seek employment in richer economies. International migration has become a large and growing phenomenon, with more than 200 million people now living outside of their home countries for extended periods.and informal employment to survive. Often this is in unseen and underappreciated jobs in agricultural, domestic work, the service sector, subcontracted maintenance services, or atomized supply chains.

The authors, however, also make clear that one of the front lines against the current crisis in capitalism has been the countermovement of union campaigns in immigrant workplaces. In order to build a more democratic and equitable society out of the crisis, workers and their organizations must lift up the bottom of the labor market and build new models of worker representation in those sectors. Unions, struggling to reverse declining membership and account for the growing contingent and informal workforces, have developed creative organizing strategies for protecting and representing workers in changing workplaces. This has often been done by embracing community-based organizations, building trust with immigrant workers, and taking on their unique challenges in societies where immigrants are too often excluded from basic rights.

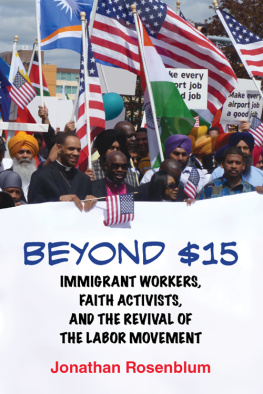

In the United States, from the time of Samuel Gompers until 2000, official union policy too often reflected national immigration policies and was discriminatory and protectionist in nature. This closed perspective on collective bargaining extended to women and workers of color in many cases. Yet, historically, immigrant workers have also been a source of activism, creativity, and power in organized labor. In recent years, union practitioners in nearly every sector have had to face the obvious conclusion that in a globalized economy, the strength of the labor movement depends on organizing and fighting for all workers, regardless of national origin.

From my time with the United Food and Commercial Workers International Union to my current role at the AFL-CIO, I have seen a remarkable transition in the labor movement. After years of seeing employers use immigration law and employer sanctions to undermine organizing drives among undocumented immigrants, thus jeopardizing standards for all workers, I was involved in the hard internal politics behind the labor movements historic call for legalization and immigration reform in 2000. I drew hope from the 2003 Immigrant Workers Freedom Ride. In 2006, with a small delegation of union officials, I witnessed a group of Latino immigrants in a chapter of the National Day Laborers Organizing Network (NDLON) employ the strategies and tactics of an earlier era of the labor movement and reach a consensus not to work for less than a $15 an hour. Subsequently, the national AFL-CIO passed a resolution that encouraged worker centers to affiliate with its national and local labor union bodies. This dramatic change in labor union politics has resulted in connecting AFL-CIO affiliates with worker centers and their networks like NDLON in dynamic partnerships to expand the labor movement and adopt new organizing strategies.

The resolution was both a recognition of the growing importance of worker centers in immigrant and other marginalized communities left behind by industrial for example, has evolved from a fight to enforce labor standards to a comprehensive initiative to address the structural exploitation of the industry and ingrained inequities in the carwashero community. By building trust with a network of community-based organizations, it has utilized the institutionalized power of a labor union to begin to reshape the carwash industry and has adopted movement-based aspects of worker center organizing to address broader issues in the immigrant community.

In other cases, too, the AFL-CIO has found that worker movements are often in need of institutional support. Established institutions can bring not only expertise and funding, but also can open political spaces not available to immigrant workers and local organizations. When movement and institution forces come together in this way workers can build power even in informal or contingent employment relationships.

For example, the National Domestic Workers Alliance built relationships with local unions to gain support for organizing and policy initiatives. These relationships eventually led the AFL-CIO to push for the International Labour Organizations (ILO) Domestic Workers Convention (Convention 189) and the inclusion of domestic workers in the ILO process, ceding a seat to a domestic worker and encouraging eleven other representative organizations to do so as well. In 2011, the National Taxi Workers Alliance was granted an Organizing Charter by the AFL-CIO, giving it affiliate status in the Federation, despite being an organization made up of independent contractors. The New York City Taxi Workers have used powerful movement building and their union affiliation to leverage demands for a fare increase and the establishment of a health fund with the NYC Taxi and Limousine Commission. The Alliance is now working with the AFL-CIO Organizing Department to build thirty locals of taxi drivers across the United States in the next seven yearsall unified under the national charter.

To be sure, as Mobilizing against Inequality lays out, the challenges associated with organizing immigrant workers are many and it is often difficult to navigate competing institutional and movement priorities. When intentional collaborative work is done, true partnerships and affiliations will be meaningful. But, after affiliations began in 2006, some partnerships stagnated as they were formed prior to building a meaningful relationship. At the first Worker Center Advisory Council meeting on January 25, 2013, between the AFL-CIO and worker center leaders, one representative stressed that active worker centers do not want to be junior partners in a static state federation of central labor councils.