GREGORY E. PENCE

BROADVIEW PRESS www.broadviewpress.com

Peterborough, Ontario, Canada

Founded in 1985, Broadview Press remains a wholly independent publishing house. Broadviews focus is on academic publishing; our titles are accessible to university and college students as well as scholars and general readers. With 800 titles in print, Broadview has become a leading international publisher in the humanities, with world-wide distribution. Broadview is committed to environmentally responsible publishing and fair business practices.

2021 Gregory E. Pence

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, kept in an information storage and retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or otherwise, except as expressly permitted by the applicable copyright laws or through written permission from the publisher.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Title: Pandemic bioethics / Gregory E. Pence.

Names: Pence, Gregory E., author.

Description: Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: Canadiana (print) 20210205490 | Canadiana (ebook) 20210205644 | ISBN 9781554815210 (softcover) | ISBN 9781770488090 (PDF) | ISBN 9781460407585 (EPUB)

Subjects: LCSH: EpidemiologyMoral and ethical aspects. | LCSH: Medical ethics. | LCSH: Public healthMoral and ethical aspects. | LCSH: Bioethics.

Classification: LCC RA652 .P46 2021 | DDC 174.2/944dc23

Broadview Press handles its own distribution in North America:

PO Box 1243, Peterborough, Ontario K9J 7H5, Canada

555 Riverwalk Parkway, Tonawanda, NY 14150, USA

Tel: (705) 743-8990; Fax: (705) 743-8353

email:

For all territories outside of North America, distribution is handled by Eurospan Group.

Broadview Press acknowledges the financial support of the Government of Canada for our publishing activities.

Edited by Martin R. Boyne

Book design by Chris Rowat Design

PRINTED IN CANADA

CONTENTS

PREFACE

Nearly 50 years ago, bioethics captivated me when I first published a note in the Hastings Center Report. Since then, bioethics has become the most intellectually exciting field in academia today. When China locked down 46 million citizens in Wuhan in December 2019, I knew that bioethics had just met the biggest issue of its modern life. This book explores the many ethical issues raised by this new pandemic.

Of course, pandemics have hurt humans before, and previous mistakes in confronting pandemics are worth learning, lest we repeat those errors. This books first two chapters review that history. Good bioethics also builds on good facts, so the next chapter explores what we know about viruses in general and SARS-CoV-2 in particular. After that, the fourth chapter discusses four approaches that governments around the world used to confront the coronavirus, with varying results and philosophical assumptions. Several issues emerge in many chapters: just distribution (of ventilators, vaccines, harms of lockdowns), vaccine passports, rollout of vaccines, leadership, and trade-offs between saving lives in the ICU versus saving the economy.

Ethical theory and philosophical tools can illuminate issues arising from pandemics, and for me, the best approach to them is not top-down but bottom-up, using theories that emerge in a specific context, for example, utilitarianism in discussing allocation of vaccines, or using a particular concept, such as the Trolley Problem, to offer new insights. In my career, Ive often been amazed at how, when I drill down deep into a complex case, new ethical issues appear that I hadnt seen at the start, such as those that emerge about immunity passports. Philosophical perspectives also arise when discussing the four general approaches to the pandemic by countries as different as Canada and Niger.

Of course, it is easy to look back a year and see the mistakes that were made, but in the midst of life-and-death decisions, no such ease can be had. Anyone writing about pandemic ethics should do so with a large amount of humility, knowing how easy it is to get facts wrong, miss important issues, or incorrectly anticipate consequences. Any mistakes of that nature are mine alone, but I hope that readers will, by the end of the book, understand that we all must fight pandemics together.

NOTES TO THE READER

For convenience in this book, the medical condition COVID-19 is written simply as Covid, and the virus SARS CoV-2 is written as SARS2.

Every effort has been made to make this book as accurate as possible, but the worlds knowledge of SARS2 and its variants is evolving quickly. Please email the author () about any topic that needs to be updated or clarified and future editions of this text will address those concerns.

CHAPTER 1

HISTORICAL EPIDEMICS

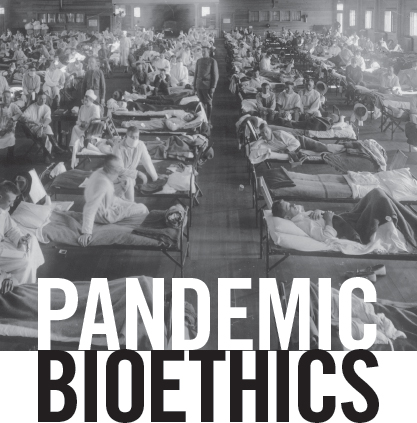

The great English science journalist Laura Spinney wrote one of the definitive accounts of the Spanish flu of 1918, a book that was little read until the coronavirus appeared in 2020. In Pale Rider: The Spanish Flu of 1918 and How It Changed the World, she introduced her subject thus:

The Spanish flu infected one in three people on earth, or 500 million human beings. Between the first case recorded on 4 March 1918, and the last sometime in March 1920, it killed 50100 million people, or between 2.5 and 5 percent of the global populationa range that reflects the uncertainty that still surrounds it. In terms of single events causing major loss of life, it surpassed the First World War (17 million dead), the Second World War (60 million dead) and possibly both put together. It was the greatest tidal wave of death since the Black Death, perhaps of human history.

As philosopher George Santayana famously observed, Those who are ignorant of history are condemned to repeat its mistakes. We cannot undo history, but we can learn from it. We can learn from the mistakes of past societies that confronted pandemics such as the Spanish flu that Spinney discusses. Maybe we can even learn how to prepare for future pandemics.

This chapter addresses historical pandemics and their bioethical issues, including plague, cholera, malaria, smallpox, and the Spanish flu of 1918. In the next chapter, we examine more modern pandemics, especially those caused by viruses such as polio and Ebola.

When an infectious disease affects only one region, its an epidemic, but when it spreads to several continents, its a pandemic. Pandemics are not new in human history, yet as Albert Camus wrote in The Plague, Everybody knows that pestilences have a way of recurring in the world, yet somehow we find it hard to believe in ones that crash down on our heads from a blue sky. There have been as many plagues as wars in history, yet always plagues and wars take people equally by surprise.

Overall, germs dont care whether we accept them or not; they dont care about who is virtuous or who is vicious, who deserves to die and who doesnt, who looks clean and who looks dirty. When then-president Donald Trump invited guests to the Rose Garden of the White House in September 2020, SARS2 hitched a ride and did not distinguish between the famous and the anonymous. Viruses just want hosts to use to replicate themselves. The recent novel