Introduction

THERE IS A TWO-STOREY WHITE HOUSE ON THE WATERFRONT AT Opononi, a small town in Hokianga, on the north-west coast of the North Island of New Zealand. When it was first completed, around 120 years ago, it was described as the show palace of Hokianga, and it is not hard to understand why. Surrounded by a large garden of specimen plants, both native and exotic, and with an interior festooned with objects its owner, John Webster, had collected from across the world, it made a grand and optimistic statement about Websters place in Hokianga and Hokiangas place in the young colony.

When I first saw the house in the late 1980s, it was less a show palace than a relic. It was shown to me as a 20-year-old university student by a friend, one of Websters great-great-granddaughters, during a mid-winter holiday. On a miserable June day, we waited for the rain to stop before wandering along the road to the local shop to buy a newspaper. Halfway there, she suggested we stop and have a look at something. We headed off the footpath and down into a ditch, making towards what looked like a dense forest of undergrowth. I struggled to imagine what could be of any interest back there, but when I looked past the tangle of weeds I saw a rundown but obviously large dwelling. I moved around to try to get a better view, but the mature trees and low scrub made it impossible to see the house completely unobscured. The general impression was clear, though. The white paint was peeling, the iron roof was rusting and the place had a look of almost total dereliction, not helped by the overcast sky and the general sense of melancholy that pervades a seaside town in winter. I came away with a feeling of sadness that something so grand had fallen into decay, but also with a feeling of intrigue. Who, I wondered, would build something of that size in an unassuming little town like this?

On the face of it, the answer is straightforward. The builder, John Webster, had come to New Zealand from Scotland via Australia in 1841 to seek his fortune, and in that he succeeded. Initially he worked gathering kauri timber on behalf of local merchants, as well as setting up as a small-time mercantile trader in his own right. Then, from the 1850s, through a mixture of commercial nous and a fortuitous marriage, he became the leading timber merchant in Hokianga at a time when demand for the areas kauri timber was consistently high and when both domestic and international markets were abundant. The mansion reflected his economic importance, while its contents, including weapons and other artefacts from Britain, Australia and the Pacific, as well as New Zealand, provided clear evidence of his life as an adventurer roaming the edges of the British Empire. But if we look a little closer, the answer to my question becomes more complex. Websters home reflected his expansive life and wealth, but it also reflected the nature of colonial Hokianga. The house might have been built with profits from the timber trade, but securing that wealth had made Webster dependent on co-operation with Mori. Websters home was less a monument built on a solid foundation of imperial triumph than a structure resting on the shifting ground of MoriPkeh interaction.

Websters life in Hokianga over the more than 60 years he lived there was characterised by commercial success, but it was also shaped by accommodation and compromise. The economic influence that he enjoyed and the political power that he wanted to claim were both circumscribed by the daily realities of the area in which he lived. Unlike settlers in some other parts of New Zealand, Webster found that Mori were a constant presence in his life right up until the time he finally left to live in Auckland, making him a useful window through which to view shifting relationships and social boundaries between Mori and Pkeh in Hokianga during the second half of the nineteenth century.

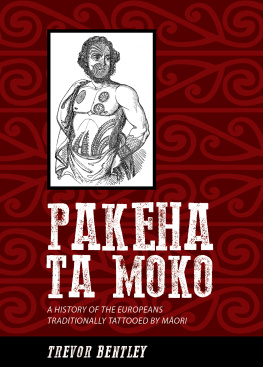

But that study might also have had to take into account a tradition in New Zealand history writing that portrayed the countrys pre-colonial and colonial past as contested. Writers such as Judith Binney, Alan Ward and Keith Sorrenson, from the 1960s through to the early 1980s, portrayed nineteenth-century New Zealand as a place where Mori and Pkeh were entwined in each others lives, often with Pkeh playing a subordinate role in what was, at least to begin with, an overwhelmingly Mori world.

From the 1980s, this two-sided view of New Zealands past was pushed in a new direction following the mobilisation of Mori political concerns, often referred to as the Mori renaissance. Influenced by writers such as Ranginui Walker, some historians started pointing to the racism of Pkeh settlers and government officials as being at the heart of colonisation. Angela Ballara, for example, saw settlers racism as central to the marginalisation of Mori, and claimed that in the early days of settlement, In stark contrast to the doughty heroes of the pioneering histories, settlers became, if not quite villains, then at least figures of oppression.

One response to this shift was to stop studying settlers, at least in frontier settings, so that the pakeha frontier historiographically [became] a location of avoidance.

At around the same time, the interaction between Mori and Pkeh in the nineteenth century became the focus of a new branch of historical investigation; namely, the Treaty of Waitangi claims settlement process. Because this process is designed to assess grievances against the Crown in order to make a case for redress, it focuses on the harm suffered by iwi at the hands of the Crown. This approach reflects claimants need to demonstrate loss, and the governments present-day approach to claims settlement, which dictates that restitution can only be sought from the Crown and not by lodging claims for privately owned land or other resources. As historian Tony Ballantyne points out, this makes the work of the Waitangi Tribunal more palatable to the broader public, but it has also acted to downplay the role of colonial settlers as active players in the historical process of colonisation. As Michael Belgrave put it:

The broad historical obsessions class, capitalism, gender or racism have little relevance as they are unable to compensate claimants for past injustices. The Crown has to be found, if not all knowing and all seeing, at least all responsible. This takes the heat off capitalists, patriarchs and

Settlers are by no means absent from the investigations into historical grievances, but the context in which those investigations take place means that they are decentred, while the governments actions towards and agreements with Mori are foregrounded. This has allowed Pkeh New Zealanders to remain largely untroubled by the role their forefathers may have played in colonialism, even as the Treaty of Waitangi has gained a higher profile in public life.

Placing the Treaty at the centre of MoriPkeh relations comes through in other areas of New Zealand history writing, where it is seen as one of several watershed moments of change, as the foundational moment in the nations history and the point from which all subsequent cross-cultural history flowed. It is the point at which Mori and Pkeh were thrown together before being driven apart by war, confiscation and demographic swamping from the 1860s.