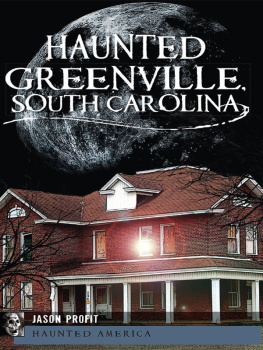

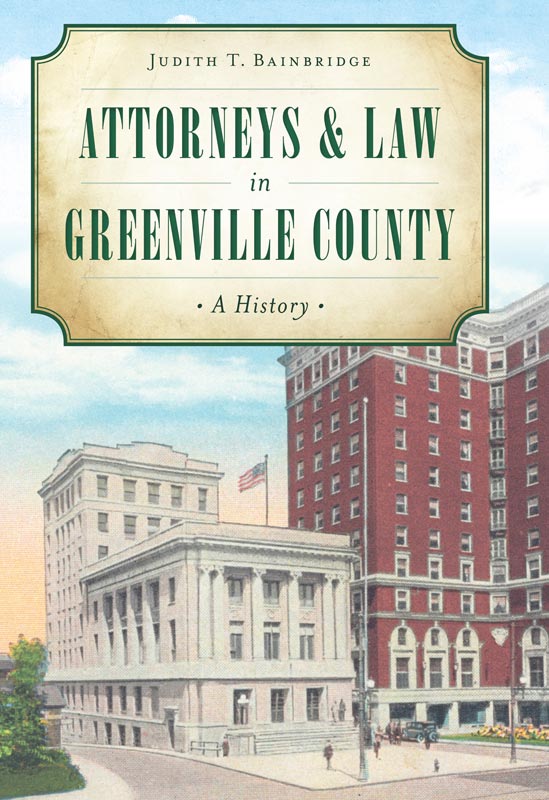

Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC 29403

www.historypress.net

Copyright 2015 by Judith T. Bainbridge

All rights reserved

Cover postcard images courtesy of the Greenville County Library System.

First published 2015

e-book edition 2015

ISBN: 978.1.62585.659.3

Library of Congress Control Number: 2015946491

print edition ISBN 978.1.46711.914.6

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and

The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

Acknowledgements

Writing the history of the Greenville bench and bar since 1786 has been a combination of challenges, discoveries and a deep and abiding appreciation for the helpfulness of so many local lawyers and judges. When I agreed in September 2013 to research and write this history, I thought that I would finish it in three or four months. That it has taken more than a year is a testimony to the richness, variety and complexity of available materials, as well as to the need to place recent history in context. Determining what contemporary people and events should be included was by far the greatest writing challenge, and I was most fortunate to have so much help.

Librarians at the South Carolina Room of the Hughes Main Library were, as always, most helpful. Internet sources have been invaluable, particularly the Library of Congress website Chronicling America. Many of the brief biographies included in the text come, in part, from the University of South Carolina School of Laws Memory Hold the Door tributes; other biographical resources, especially those for U.S. congressmen and members of the South Carolina General Assembly, are also available on the web. For recent biographical data, I made use of firm websites and lots of telephone conversations.

While electronic access has provided dates, facts and even memorable phrases, it has been the interviews, e-mails and telephone calls to attorneys and judges, both active and retired, that have provided essential perspective. They have responded to my questions, shared anecdotes and offered photographs, illustrations and even manuscripts; they have, most of all, helped a non-lawyer understand what lawyers seem to know instinctively. (Two Circuit Court judges sketched diagrams of the state and federal court systems before I thoroughly grasped their intricacies.)

Among those who have responded to my need for assistance and to whom I am grateful are Clerk of Court Paul Wisenheimer; Registrar of Deeds Tim Nanney; lawyers James Chip Price, Julian Dority, John Cheros, Rita McKinney, Diane Smock, John Mauldin, James Parham, James Watson, Merl Code, Joe Watson; Master in Equity Charles Simmons; and especially Judge Robert Jenkins. Sibet Partee shared her husbands public defender files. Frank Eppess stories of his father, as well as his insight into the legal profession over the last twenty years, were invaluable. Judge Gary Hill will recognize some of his perceptive and helpful comments in my discussion of Fourth Circuit Appeals Court judges, and Appeals Court Judge Bill Traxler cheered me on. Former Governer Richard Rileys discussion of court and governmental reforms in the 1970s provided insight that I could never have gained otherwise. Ogletree, Deakins, Nash, Smoak and Stewart attorney Jimmie Stewart not only shared the 150-page firm history that he is currently completing but also spoke frankly about labor law in the 1960s and 1970s. Former Legal Service General Counsel Tom Bruce read and commented on the entire text and offered sage advice, as did Bill Clarke, who picked up a rash of small errors in a final read. I will never forget the graciousness of Judge Victor Pyle, who not only gave me a grand tour of the Greenville Courthouse and Judicial Centerand shared a wealth of data, including past bar association annualsbut also provided written comments on the changes in legal practice over the past forty years that were remarkably helpful.

Presidents Bill Clarke (2013), Courtney Atkinson (2014) and Travis Olmert (2015), as well as the members of the Executive Committee of the Greenville Bar Association, several of them friends and acquaintances of many years standing, have been unfailing in their support and constant in their encouragement. I must also thank bar association executive secretary Melinda Davidson for her timely responsiveness and all-around good nature and total support.

Finally, I am particularly appreciative of the time, care and concern that Circuit Court Judge Edward Miller and Legal Services senior litigator Kirby Mitchell have given to this project. From the very first informal discussion of the possibility of writing a history of the Greenville bar, Judge Miller has been totally supportive. He encouraged the project, contributed an articulate discussion of its background at the Continuing Legal Education Seminar in February 2014 and read and commented on every chapter. Kirby Mitchell has, for more than a year, acted as a liaison with the bar association. A dear friend of many years standing, his enthusiasm for the project has been matched by the wisdom of his suggestions and his real help as an editor and sometimes cheerleader who has read every pagesome more than onceof the manuscript.

My husband, Bob Bainbridge, has lived with this project for many months. Not only has he, too, read every page, but he has also listened to my concerns and has even, occasionally, enjoyed my discoveries. I am totally grateful for his love and patience.

Chapter 1

Law and Order in the Wild West

17861820

South Carolina legislators chartered Greenville County on March 22, 1786, in order to bring a semblance of law and order to the untamed western part of the state. Before the American Revolution, the land between the Saluda and the Enoree Rivers in the foothills of the great mountains had been Cherokee hunting grounds, off limits to white settlers. One of the very few exceptions was Richard Pearis, an Irish Indian trader who in 1770 managed to acquire (semi-legally) about twelve square miles of land east of the Reedy River and built a plantation and trading post at the shallowest point of the river near modern-day downtown Greenville. During the Revolution, the backcountry was the site of violent skirmishes between the Patriots and the Loyalists (or Tories), with Pearis included among the latter. Afterward, the new State of South Carolina claimed his plantation and the hunting grounds of the Cherokees, who had also sided with the British during the conflict.

At the conclusion of the war, the state, devastated by seven years of conflict, was in a perilous financial condition. The government, whose primary resource was land, owed money to the men who had fought with the Patriots and those whose property had been confiscated. To cover those debts, starting in May 1784, South Carolina granted or sold the land that would be Greenville County to hundreds of claimants. While most grantees planned permanent settlement, some were speculators looking to make a fast profit. Many settlers were quick-tempered Scots-Irish who settled disagreements with fists, knives or lawsuits.