Incarcerated Stories

CRITICAL INDIGENEITIES

J. Khaulani Kauanui and Jean M. OBrien, series editors

Series Advisory Board

Chris Anderson, University of Alberta

Irene Watson, University of South Australia

Emilio del Valle Escalante, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Kim TallBear, University of Alberta

Critical Indigeneities publishes pathbreaking scholarly books that center Indigeneity as a category of critical analysis, understand Indigenous sovereignty as ongoing and historically grounded, and attend to diverse forms of Indigenous cultural and political agency and expression. The series builds on the conceptual rigor, methodological innovation, and deep relevance that characterize the best work in the growing field of critical Indigenous studies.

Incarcerated Stories

Indigenous Women Migrants and Violence in the Settler-Capitalist State

Shannon Speed

The University of North Carolina Press CHAPEL HILL

This book was published with the assistance of the Anniversary Fund of the University of North Carolina Press.

2019 The University of North Carolina Press

All rights reserved

Set in Merope Basic by Westchester Publishing Services

Manufactured in the United States of America

The University of North Carolina Press has been a member of the Green Press Initiative since 2003.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Speed, Shannon, 1964author.

Title: Incarcerated stories : indigenous women migrants and violence in the settler-capitalist state / Shannon Speed.

Other titles: Critical indigeneities.

Description: Chapel Hill : University of North Carolina Press, [2019] | Series: Critical indigeneities | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019008164| ISBN 9781469653112 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781469653129 (pbk : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781469653136 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: WomenEffect of imprisonment onUnited States. | MexicansEffect of imprisonment onUnited States. | Central AmericansEffect of imprisonment onUnited States. | WomenUnited StatesSocial conditions21st century. | MexicansUnited StatesSocial Conditions21st century. | Central AmericansUnited StatesSocial Conditions21st century. | WomenUnited StatesEconomic Conditions21st century. | MexicansUnited StatesEconomic Conditions21st century. | Central AmericansUnited StatesEconomic Conditions21st century.

Classification: LCC HV8738 .S63 2019 | DDC 362.83/9814092397073dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019008164

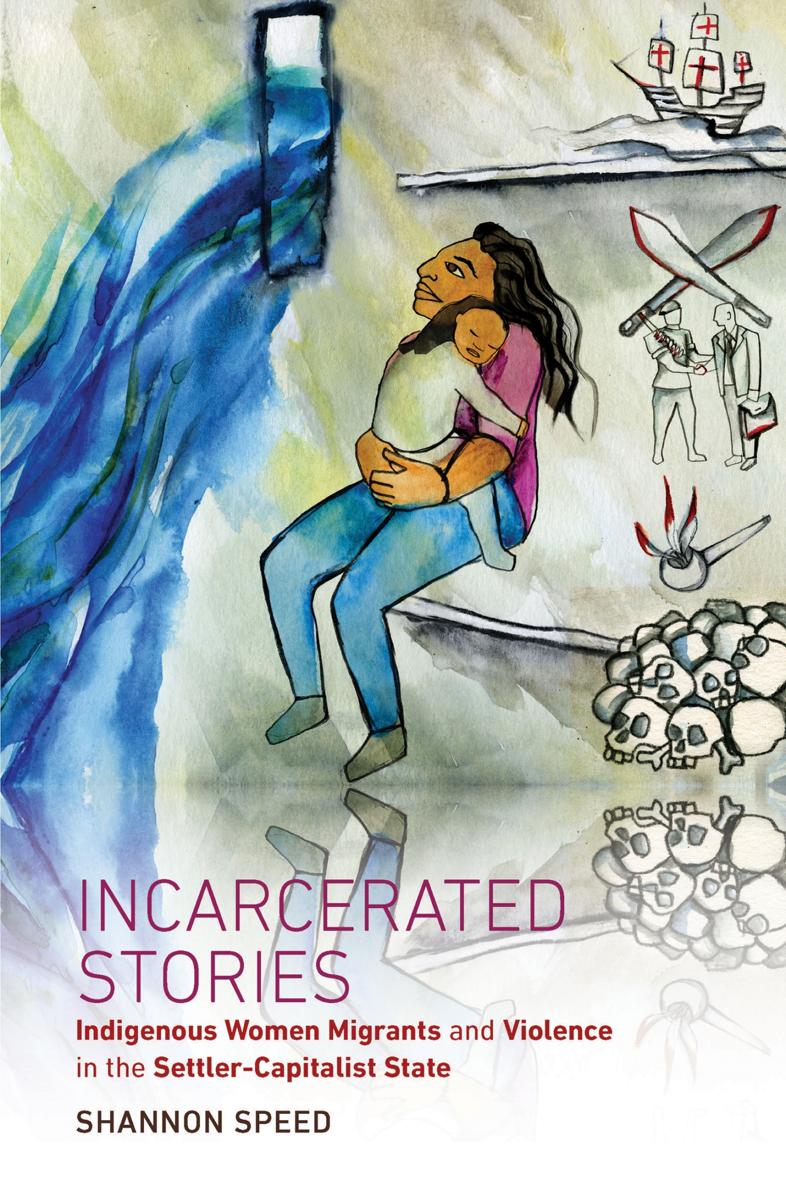

Cover illustration: Art by Micah Bazant. Originally commissioned by CultureStrike for the Visions from the Inside (2015) exhibition. Courtesy of the artist.

For my mother, Iris Speed

For all the brave women who confront the structures of power daily in pursuit of a life free of violence

Contents

Figures

Incarcerated Stories

CHAPTER ONE

Power and Vulnerability through Indigenous Womens Stories

Ysinia,a Maya Mam woman from near Quetzaltenango, Guatemala, left home, fleeing a husband who beat her repeatedly and threatened to kill her. When his last beating nearly succeeded in realizing that threat, she made the difficult decision to leave, devastated to part with her family but in fear for her life. The trip north was not easy. She was detained by Mexican immigration agents who mocked her and questioned her about why an Indita would venture to leave her communitydidnt she know it was dangerous? Farther north, in Reynosa, she was abducted by armed men and held in a house for ransom. There she witnessed another woman, who spoke a different Mayan language and very little Spanish, being brutally beaten by their captors for failing to get the required money. After Ysinias ransom was paid, she was released and made her way to the border. However, after a very harrowing but ultimately successful crossing into the United States, the two men who she and others had paid to bring them across separated her from the group and tried to rape her. She fought back and her screams got the attention of others who came to her aid. Unfortunately, the ruckus created by the incident drew the attention of the border patrol and Ysinia was apprehended. When I met her, she was being held at the T. Don Hutto immigration detention facility in Taylor, Texas. Inside Hutto, she spoke of the unbearable tedium of the days that led her again and again to thoughts of all that has happened to her, the bitter sorrow of being separated from her children, and her struggle to fight off paralyzing fear and depression as she awaited her fate as an asylum seeker in the United States.

Indigenous women in the Americas are subject to extraordinary and systematically unseen levels of violence. This is true from the northern reaches of Canada and Alaska to the tip of Tierra del Fuego. Indigenous women migrants are emblematic of this social reality; their liminality as they move through social space renders them both vulnerable and invisible in a multiplicity of ways. The myriad forms of violence they suffer are neither random nor products of chance. Rather, they reflect the structural brutality of inequalities of gender, race, class, and nationality, linked to neoliberal logics in which market forces define social relations. Indigenous women migrants stories thus have much to tell us not only about violence but also about how state power is working in the current moment.

In this book, I depart from the oral histories of Indigenous women migrants from Mexico and Central America to provide an analysis of settler state power. Their stories are invariably compelling, reflecting both tremendous violence that shocks the conscience and human strength that boggles the mind. These women have suffered human rights violations at every step of their journey. Many experience domestic violence serious enough to compel them to leave home, community, and family, and to undertake a dangerous journey with an unknown outcome. Others undertake that precarious journey in an attempt to flee gang violence or cartel threats. Authorities in their home countries are unwilling or unable to protect them from this violence or to hold accountable those who perpetrate it. Their journey inevitably takes them through Mexico, where they may experience violence at the hands of human traffickers, petty criminals, gangs, and cartels, as well as the military, police, and immigration authorities. Once they enter the United States as immigrants, they face potential incarceration under draconian immigration laws and policies ostensibly designed to impede terrorism. Those who avoid detention but remain undocumented often face new vulnerability to violence at the hands of strangers or family members because of a fear of reporting. Indeed, violence so thoroughly marks the lives of Indigenous women migrants that it is hard for many to imagine a life in which they are not vulnerable to it.

That vulnerability is not a condition of the women themselves, but rather a structural condition. As I will show in the pages that follow, this condition was consciously created through the settler-colonial process, and, though functioning differently across space and time, consistently deploys racial and gender ideologies to manage the ongoing business of settler occupation. I use the terms vulnerable and vulnerability purposefully in this work. I am sympathetic to critiques of scholars like Sherene Razack who have signaled the potential consequences of using the term, which could include interpreting vulnerability as an existential condition and might then even imply blaming women for the violence they experience (this happened because they were vulnerable); underestimating womens agency (the womens lives are simply a product of structural forces); or taking the focus off the perpetrators (particularly the settler state) (see Razack 2016). However, I want to use the term here to do precisely the opposite, to reveal the multiple ways in which Indigenous women are rendered vulnerable to a range of perpetrators through structures of settler capitalist power, and act to resist by surviving. Vulnerability as I discuss it here is not an inherent characteristic, but rather one imposed in multiple, intersecting ways as power is deployed in the world. In Spanish, this difference would be expressed by saying that, rather than being