Thank you for buying this ebook, published by NYU Press.

Sign up for our e-newsletters to receive information about forthcoming books, special discounts, and more!

Sign Up!

About NYU Press

A publisher of original scholarship since its founding in 1916, New York University Press Produces more than 100 new books each year, with a backlist of 3,000 titles in print. Working across the humanities and social sciences, NYU Press has award-winning lists in sociology, law, cultural and American studies, religion, American history, anthropology, politics, criminology, media and communication, literary studies, and psychology.

SLAVERYS EXILES

SLAVERYS EXILES

THE STORY OF THE AMERICAN MAROONS

Sylviane A. Diouf

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS

New York and London

www.nyupress.org

2014 by Sylviane A. Diouf

All rights reserved

Book designed and typeset by Charles B. Hames

References to Internet websites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing.

Neither the author nor New York University Press is responsible for URLs that

may have expired or changed since the manuscript was prepared.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Diouf, Sylviane A. (Sylviane Anna), 1952

Slaverys exiles : the story of the American Maroons / Sylviane A. Diouf.

pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8147-2437-8 (hardback)

1. MaroonsSouthern StatesHistory.

2. Fugitive slavesSouthern StatesHistory.

3. Southern StatesRace relationsHistory. I. Title.

E450.D56 2014

305.800975dc23 2013029821

New York University Press books are printed on acid-free paper, and their binding materials are chosen for strength and durability. We strive to use environmentally responsible suppliers and materials to the greatest extent possible in publishing our books.

Manufactured in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Also available as an ebook

To Sny and Maya

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Everything starts with research and the people I am particularly indebted to for the existence of this book are the numerous archivists who have contributed their knowledge of the materials I was looking for and those I did not know existed.

I got wonderful assistance at the North Carolina State Archives from a great, dedicated staff. My sincere thanks go in particular to Christopher Meekins who enthusiastically opened up a whole treasure trove of documents and even looked for others on his lunch break. I am also very grateful to Vann Evans for his gracious and generous help. The archivists at the Library of Virginia, the South Carolina Department of Archives and History, the Georgia Historical Society, the Georgia Department of Archives and History, the Hargrett Library at the University of Georgia, and the New Orleans Public Library have been splendid.

Many thanks go to Diana Lachatanere at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library; James D. Wilson, Jr., at the Center for Louisiana Studies of the University of Louisiana at Lafayette; and Melissa Stein at the Louisiana State Museum.

Debbie Gershenowitz, then senior editor at NYU Press, was an enthusiastic supporter from the start and I am so immensely grateful to her for her wonderful work on this book. My deepest appreciation goes to my editor, Clara Platter, who skillfully made this project a reality.

As always, my family has been actively supportive. My mother, Martine, Alain, and Mariam always my cheerleaders: they listened to me with patience, understanding, and encouraged me every step of the way. Maya, smart well beyond her years, has been pure joy. Last on this page, but always first on my mind, Sny has been my accomplice, my supporter-in-chief, and my confidante; always caring and thoughtful. He has enriched my life in so many ways; I am proud of his accomplishments and prouder yet of being his mother.

INTRODUCTION

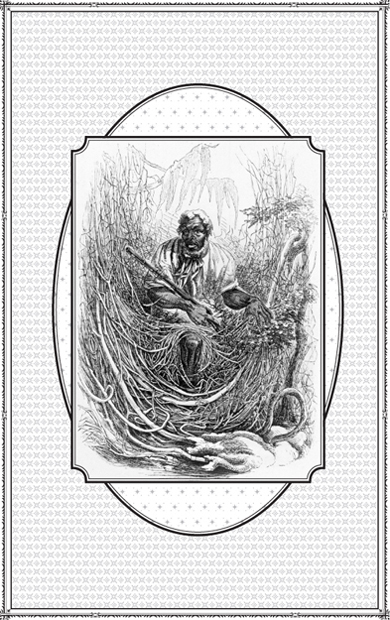

LORD, Lord! Yes indeed, plenty of slaves uster run away. Why dem woods was full o em chile, recalled Arthur Greene of Virginia. They were Africans two days off the slave ship and people who intimately knew the geographic and social environment, its constraints, and the way to navigate it. They were not truants who had absconded for a short while, to rest, avoid a beating or recover from one, take a break, or visit relatives and friends on neighboring plantations. They were not runaways making their way through the wilds to reach a Southern city or a free state or to cross international borders to find freedom under a foreign power. The people whose stories are the subject of this book went to the Southern woods to stay.

Although it is based on scores of cases, Slaverys Exiles neither attempts to relate all documented instances of marronage nor is it about all maroons. The individuals and groups studied here shared three key characteristics: they settled in the wilderness, lived there in secret, and were not under any form of direct control by outsiders.seem to encompass all maroons, do not. The well-known maroons of Spanish Florida, for example, are absent from these pages because they were officially recognized as freeeven if in a limited wayby Spain who offered sanctuary to runaways from the British colonies and later the United States. People who settled among American Indians in their territories are not covered either for the same reason. They lived in villages and towns and not the wilderness, where their hosts openly accepted them and controlled them to various degrees.

This book also excludes individuals and communities that some scholars define as maroons, based on a broad definition of marronage as the act of fleeing enslavement. In this vein historian Steven Hahn notes that black enclaves in the North, which attracted new runaways and gave rise to autonomous leadership, social structures, institutions, and cultural practices are historically specific variants of the broad phenomenon of maroons. But by lumping together divergent experiences, we run the risk of flattening each groups specificities and of obscuring the maroon experience (as defined here) in favor of better-known forms of resistance. Moreover, this approach hides key differences between maroons and runaways who lived in black enclaves. The latter refused enslavement but not the larger society, which they wanted to be a part of even if they knew it could only be at its periphery. Although they organized to challenge them, runaways and free blacks continued to live under the discriminatory laws of white society, still subservient and controlled.

The experience of the people hidden in the wildsthe maroons examined in this bookcould not have been more different. Autonomy was at the heart of their project and exile the means to realize it. The need for foolproof concealment, the exploitation of their natural environment, and their stealth raids on farms and plantations were at the very core of their lives. Secrecy and the particular ecology of their refuges forced them to devise specific ways to occupy the land and to hide within it. Negotiating and manipulating their landscape dictated the types of dwellings they could erect, when they could walk outside, or light a fire. They determined if, where, and how much land they could cultivate, what kinds of animals they could keep, how they got weapons and clothes, and what types of interaction they could have with the world they had left behind.