First published in 2019 by

Berghahn Books

www.berghahnbooks.com

2019 Mikkel Bille

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purposes of criticism and review, no part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without written permission of the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A C.I.P. cataloging record is available from the Library of Congress

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 978-1-78920-120-8 hardback

ISBN 978-1-78920-121-5 ebook

Acknowledgements

Doing fieldwork among the Bedouin means meeting thousands of people. There are hence too many people to be thanked for space here to allow. Among all the people who have shaped the data and analysis, there are nonetheless those without whom this work would not have been the same or even possible, particularly the late Sheikh Salame Eid of the Hamid branch of the Ammarin tribe and all members of his family. The oldest son Mohammed is particularly thanked for his friendship and help. Likewise, thanks are due to the family of Hamad Abu Lafi from the Jumman branch, and the help and friendship from their second son Talal have been indispensable. His company and eager help are greatly missed. Mtia Umm Suleiman has been a great personal inspiration and source of information. I also owe Sheikh Ibrahim and mayor Eid Shtiyyan many thanks. Their generosity, hospitality and friendship will never be forgotten, and will serve as reminders of the privilege of doing fieldwork with the Ammarin.

In Wadi Mousa, I thank Waleed al-Hassanat, Suleiman Farajat, Saad Rawajfeh, Hani al-Falahat, Zeyad al-Salameen, Erin Addison, Ismael from the Wastewater plant, and Wendy from Petra Moon Tourism Services. From around Jordan, the late Sheikh Suleiman Abu Adef Ammarin, Aysar Akrawi from PNT, Ziad Hamze, Rami Sajdi, Nicholas Seeley, Department of Statistics in Jordan, and the Royal Geographical Institute have all been helpful at various stages. The staff at the Council of British Research in the Levant deserves special thanks, particularly Bill Finlayson and Nadia Qaisi who made my fieldwork easier and my time in Amman much more comfortable. At the German Institute, I thank Nadia Shuqair for interview transcriptions. Geraldine Chatelard from the French Institute has offered indispensable help in discussing UNESCO procedures.

Special thanks are due to Victor Buchli and Chris Tilley at UCL, and Esther Fihl, Lars Hjer, Miriam Zeitzen, Michael Ulfstjerne, Stine Puri and Regnar Kristensen from the Centre for Comparative Culture Studies at University of Copenhagen who have also offered much inspiration and critical reading. Also, my thanks go to Lynn Meskell, David Wengrow, Bo Dahl Hermansen, Stephen Lumsden, Rodney Reynolds, Anna Hoare, and in particular Andreas Bandak and Tim Flohr Srensen who have been central to my thinking about the issues raised in this book. Also acknowledged are the four reviewers of earlier versions of this manuscript. And finally, I offer my thanks for support from family and friends, with special thanks to my wife Sofie for her immense support, and for accepting the conditions of fieldwork which she took part in. The funding was provided by the Danish Research School of Cultural Heritage Studies, represented by Carl Gustav Johannsen, and the Danish Research Council. Elli and Peter Ove Christensens fund prompted my initial pursuit of an academic education at UCL.

Chapter 3 builds upon and extends M. Bille, 2012, Assembling Heritage: Investigating the UNESCO proclamation of Bedouin intangible heritage in Jordan, International Journal of Heritage Studies, 18(2), 107123. Chapters 4 and 5 were previously published in altered versions in M. Bille, 2013a, The Samer, the Saint and the Shaman: Ordering Bedouin Heritage in Jordan, in A. Bandak and M. Bille, (eds), Politics of Worship in Contemporary Middle East: Sainthood in Fragile States (Leiden: Brill Publishers), pp. 101126; and M. Bille, 2013b, Dealing with Dead Saints, in D.R. Christensen and R. Willerslev (eds), Taming Time, Timing Death: Social Technologies and Ritual (Surrey, UK: Ashgate), pp. 137155. Parts of chapters 6 and 7 were published in M. Bille, 2010, Seeking Providence Through Things: The Words of God versus Black Cumin, in M. Bille, F. Hastrup and T.F. Srensen (eds), An Anthropology of Absence: Materializations of Transcendence and Loss (New York: Springer Press), pp. 167184).

I have used the English spelling for common names, places and words. To the best of my knowledge, I have otherwise adhered to the Deutsche Morgenlndische Gesellschaft standard of Arabic transliteration while also seeking to recognise the varied local pronunciation. My thanks go to Naja Bjrnsson for her guidance on Arabic transliteration, while all mistakes, of course, remain my own.

Mikkel Bille, Copenhagen, Autumn 2015

Introduction

IN THE PRESENCE OF THINGS

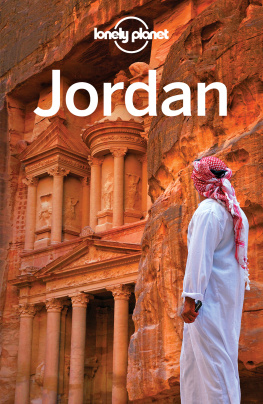

Ignorant, all of them ignorant (jhil, kulhum jhil). The judgment came without any hesitation from Husseins mouth, loaded with utter disgust. We were on our way to meet some friends in Taibeh, just south of the Petra in Jordan, when we passed the saint graves in the cemetery at Ayn Amn (figure 0.1). With an elaborate stone construction around the largest of the graves, pieces of torn cloth tied to sticks inserted into the grave, used candles, and burn marks from incense, it was evident that the graves were still used for saint intercession at least by some people.

Hussein is in his mid-twenties from the Ammarin tribe, defines himself as Bedouin, and works as a park ranger in the nearby national park of the ancient city of Petra. Unlike the older generations of Bedouin who once lived in tents and caves in the surrounding desert mountains, Hussein was born and raised in a small village, where he now lives in a house with his wife and children. His rejection should be seen in the context of religious scholars increasingly preaching a more purist, scriptural understanding of Islam in the village mosque since the late 1990s, as part of what has more generally been called the Islamic Revival (al-awa al-Islamiyya) spreading in various forms out of Saudi Arabia and Egypt. Consequences of this increasing religious awareness in the late twentieth and twenty-first century are the development of Islamic parties such as the Islamic Action Front in Jordan, discourses of a return to a true Caliphate, and a rhetoric of the existence of only one monolithic Islam and a worldwide

Contents

Contents Figures

Figures Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements

Introduction

Introduction