Complementary Studies on Trust and Cooperation in Social Settings: An Introduction

Vincent Buskens

Rense Corten

Chris Snijders

Rigorous sociologists should develop sound theoretical predictions to be tested with high-quality empirical research rather than produce teutonischer Tiefsinn devoid of empirical content.

Werner Raub

1.1 Background

The issue of cooperation has been a core topic in the social sciences for a long time, and for good reasons. Many societal matters share that everyone involved knows what they would prefer to see happening, but the incentives are such that this is hard or even impossible to achieve. Examples are abundant, and play at different levels of granularity. At the societal level, one could think of (trying to prevent) the depletion of collective resources or transitioning to a more sustainable society. At the level of organizations, one could think of trying to overcome the impulse to benefit in a business relation at the expense of the other party, or of the tendency for businesses to use legal constructs to evade taxes. Regardless of the grandiosity of these cooperation problems, similar arguments play a role in the provision of collective goods in neighborhoods or households, and even within a single person there can be friction between the current and the future self.

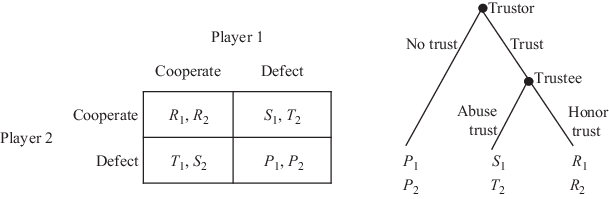

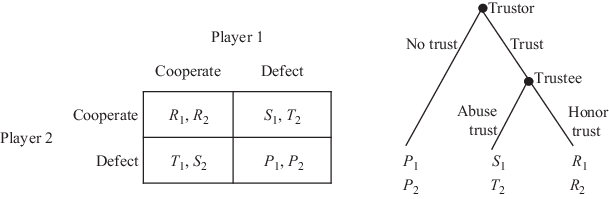

The academic literature has coined the term social dilemmas for these kinds of interactions in which sensible decisions by individual actors lead to an outcome that is inferior for all (see Raub, Corten, and Buskens 2015 for a more technical definition). For those unacquainted with the general topic, this sounds hard to imagine. How can it be that we end up in a situation where everybody agrees that an alternative outcome was possible that is better for everybody? Nevertheless, many well-known cooperation problems share this feature. The canonical example of such a problem is the famous Prisoners Dilemma (Luce and Raiffa 1957: 9495; Axelrod 1984). In this game for two actors, the two actors simultaneously choose between two actions, Cooperate or Defect, and the four outcomes that can result from these choices have benefits for both actors as in the left panel of Figure 1.1. Both actors, considering the potential choices of the other player, will conclude that to defect benefits them more than to cooperate, irrespective of what the other actor does, and hence to defect is the rational course of action for each of them. Two actors who think this way will end up with the payoffs that go with mutual defection, even though mutual cooperation would have yielded a better outcome to both.

Figure 1.1: Prisoners Dilemma (left) and Trust Game (right) (Si < Pi < Ri < Ti, i = 1,2).

Another type of exchange that differs from the Prisoners Dilemma in important aspects but nevertheless shares its social dilemma nature is the Trust Game (Dasgupta 1988), illustrated in the right panel of Figure 1.1. In this game, the moves are sequential rather than simultaneous. In the first move, the trustor chooses whether or not to place trust in the trustee. If the trustor indeed decides to place trust, the trustee decides whether to honor or abuse it. The outcomes of the Trust Game are such that after trust is placed, abusing trust is more beneficial for the trustee than honoring trust. The trustor, anticipating that the trustee will abuse trust if it is placed, will reasonably decide not to trust the trustee. As in the Prisoners Dilemma, both actors end up in a situation that is suboptimal as mutual cooperation (the trustor placing trust and the trustee honoring trust) would be a better outcome for both.

The explanation of these, already very well-known, abstract interactions immediately suggests both how theoretical arguments about cooperation problems can take shape and how scholars have tried to tackle the analysis of cooperation and trust problems. For one, these games make clear that not all social dilemmas are equal. Some fit better with the Prisoners Dilemma, where choice is simultaneous, whereas others resemble a Trust Game, where choice is sequential. Other types of games are often natural extensions of these archetypical ones. It can be sensible to assume more than two actors, more than just two behavioral choices, different kinds of payoffs, uncertainty about choices or payoffs or the type of other players, to assume repetition of interactions, embeddedness of the interactions in a larger setting, or different rules about behavior or outcomes.

Theoretical social scientists have covered a variety of such models, trying to identify the conditions under which cooperation may emerge. Such explanations may take place at several levels (cf. Kollock 1998). At an individual level, alternative psychological assumptions on preferences or rationality may be introduced to explain why individuals cooperate (see Gchter 2013). Another approach is to maintain the standard assumptions that actors are rational and selfish, and instead look for features of social conditions that make the emergence of cooperation possible (see Buskens and Raub 2013). This is the approach typically taken by sociologists, following Colemans (1987) suggestion that sociological theory ought to keep assumptions on individual behavior as simple as possible, in order to be able to study complex mechanisms on the social level in more detail. Nevertheless, also theoretical work that is primarily interested in social mechanisms often requires careful consideration of micro-level assumptions. Several well-known conditions that can facilitate cooperation included individual actors being involved in repeated interactions (Axelrod 1984), actors organized in social networks (Raub and Weesie 1990), and institutional arrangements that facilitate trust or cooperation (Greif 2006). Many authors in this volume build on one of these lines of research for explaining cooperative behavior in social dilemmas.

Part I of this book collects advancements in theoretical work in this area. In this part, some authors focus more on the essence of the trust or cooperation problems, while others concentrate more on the psychological assumptions and social conditions that can foster trust and cooperation. In addition to and in synergy with this theoretical work, researchers have invited people to the social science laboratory and have had them actually play these and similar kinds of games, trying to figure out whether or not the predictions that theoretical social science has come up with, fit with the behavior of people under strict laboratory conditions. We showcase work that fits this tradition in Part II. Finally, some research ventures outside the lab and confronts the predictions of cooperation theory, especially the ones that seem to hold under controlled conditions, with the empirical reality of everyday life. We show this kind of work in Part III.