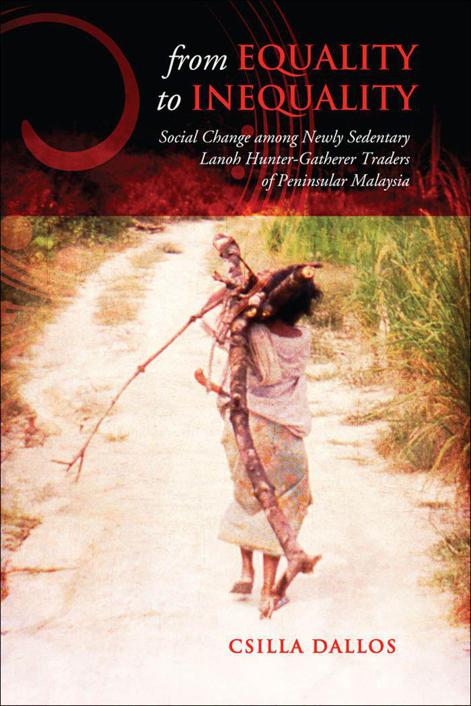

FROM EQUALITY TO INEQUALITY

Social Change among Newly Sedentary Lanoh

Hunter-Gatherer Traders of Peninsular Malaysia

How does inequality emerge in previously egalitarian societies? This question has occupied generations of anthropologists since the nineteenth century. In spite of the various theories explaining processes leading to inequality and the development of social complexity, we still have a limited understanding of the problem. This is partly because research has focused primarily on exogamous factors, and partly because the process of emerging inequality has been notoriously difficult to study empirically.

In this book, Csilla Dallos presents the results of ethnographic fieldwork among the hunter-gatherers in Peninsular Malaysia that addresses these issues. It provides rich empirical data on the effects of internal processes deemed significant in developing inequality, such as sedentism, integration, leadership competition, self-aggrandizement, marginalization, and feuding of kinship groups. By studying and interpreting social change in this previously egalitarian community of Lanoh forager-collectors, Dallos argues that, to understand emerging inequality, and to integrate anthropological models of equality and inequality, scholars need to review the conception of politics in small-scale egalitarian societies. Based on her findings, the author proposes a new model of developing inequality, one that is congruent with the principles of complexity theory.

(Anthropological Horizons)

CSILLA DALLOS is an associate professor in the Department of Anthropology at St Thomas University.

ANTHROPOLOGICAL HORIZONS

Editor: Michael Lambek, University of Toronto

This series, begun in 1991, focuses on theoretically informed ethnographic works addressing issues of mind and body, knowledge and power, equality and inequality, the individual and the collective. Interdisciplinary in its perspective, the series makes a unique contribution in several other academic disciplines: womens studies, history, philosophy, psychology, political science, and sociology.

For a list of the book published in this series see .

From Equality to Inequality

Social Change among Newly

Sedentary Lanoh Hunter-Gatherer

Traders of Peninsular Malaysia

CSILLA DALLOS

University of Toronto Press Incorporated 2011

Toronto Buffalo London

www.utppublishing.com

Printed in Canada

ISBN 978-1-4426-4222-5 (cloth)

ISBN 978-1-4426-1122-1 (paper)

Printed on acid-free, 100% post-consumer recycled paper with vegetable-based inks.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Dallos, Csilla, 1963

From equality to inequality : social change among newly sedentary

Lanoh hunter-gatherer traders of Peninsular Malaysia / Csilla Dallos.

(Anthropological horizons)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-4426-4222-5 (bound). ISBN 978-1-4426-1122-1 (pbk.)

1. Indigenous peoples Malaysia Social conditions. I. Title. II. Series: Anthropological horizons

GN635.M4D34 2011 305.89928 C2010-907616-8

This book has been published with the help of a grant from the Canadian Federation for the Humanities and Social Sciences, through the Aid to Scholarly Publications Program, using funds provided by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

University of Toronto Press acknowledges the financial assistance to its publishing program of the Canada Council for the Arts and the Ontario Arts Council.

University of Toronto Press acknowledges the financial support of the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund for its publishing activities.

ContentsMaps and FiguresMaps

Figures

TablesPreface and AcknowledgmentsThese days, I teach, and as I consider how this book took shape, I think of my students, novice researchers struggling with their material at different phases of project completion. This book came together eventually, but, as anyone who has ever worked with ethnographic material can attest, there were times when its realization was far from obvious.

This book is the outcome of nearly fifteen years of thinking and it has benefited from the help of numerous individuals and institutions. It began at the University of Toronto, when I approached my Masters supervisor, Professor Shuichi Nagata, for advice on my final research project. He handed me two articles, James Woodburns Egalitarian Society and a paper by Robert Dentan on Senoi Semai, asking if I would be interested in tackling the issues raised by these authors. I was, and this marked the beginning of my connection with the Orang Asli, the indigenous people of Peninsular Malaysia, as well as my relationship with Shuichi Nagata, who has remained my mentor over the years and to whom I feel more gratitude than I can ever express.

Or did this project start even earlier, when I signed up for my first course in cultural anthropology as an undergraduate at the University of Toronto with Richard B. Lee, whose lectures were steeped in his captivating work with the !Kung. It is to him that I owe my fascination with hunter-gatherers and their role in anthropological theory. I carried these interests with me when I transferred to McGill University, where I enrolled in a doctoral program. I owe a great deal to my thesis supervisor, Jrme Rousseau, who initiated me into the problematic of social inequality, and to the legendary archaeologist Bruce Trigger, who engaged me in discussions on social evolution. During these years, my conversations with Jrme about complexity theory turned to ways in which it could address postmodern criticisms of evolutionary thinking and thereby rescue social evolutionism from obsolescence.

When, after this conceptual preparation, it came time to decide where I would conduct my dissertation research, I had little doubt in my mind that it would be among the Orang Asli of Peninsular Malaysia. I was still uncertain, however, of exactly where and with whom I would be working. To narrow my choices, I travelled to Malaysia for a short visit, where Geoffrey Benjamin was kind enough to discuss with me potential research sites. It was Cornelia van der Sluys, however, who literally grabbed me from a hotel in Kuala Lumpur and took me to Upper Perak, where she introduced me to the Lanoh of Tawai and Air Bah. I cannot begin to describe how important this gesture was for the success of my project. It was an introduction by a trusted friend, guaranteeing that I would receive a warm welcome into the community when I returned a year later.

The dissertation (Dallos 2003) resulting from this fieldwork was put aside for some years while I grappled with the challenges of teaching. While my doctoral thesis contained the core of the argument outlined in this book, it took many further months to shape it into its present form. Though this book is based on ethnographic work, it is not framed as ethnography in the sense that its primary goal is not to present a picture of a group of people (Wolcott 2008: 44, 66). Instead, it builds on ethnographic data to develop a theoretical argument about hunter-gatherers, social change, egalitarian societies, and their role in social and human evolution. This, I believe, is where its main utility lies, both for students and professional anthropologists.