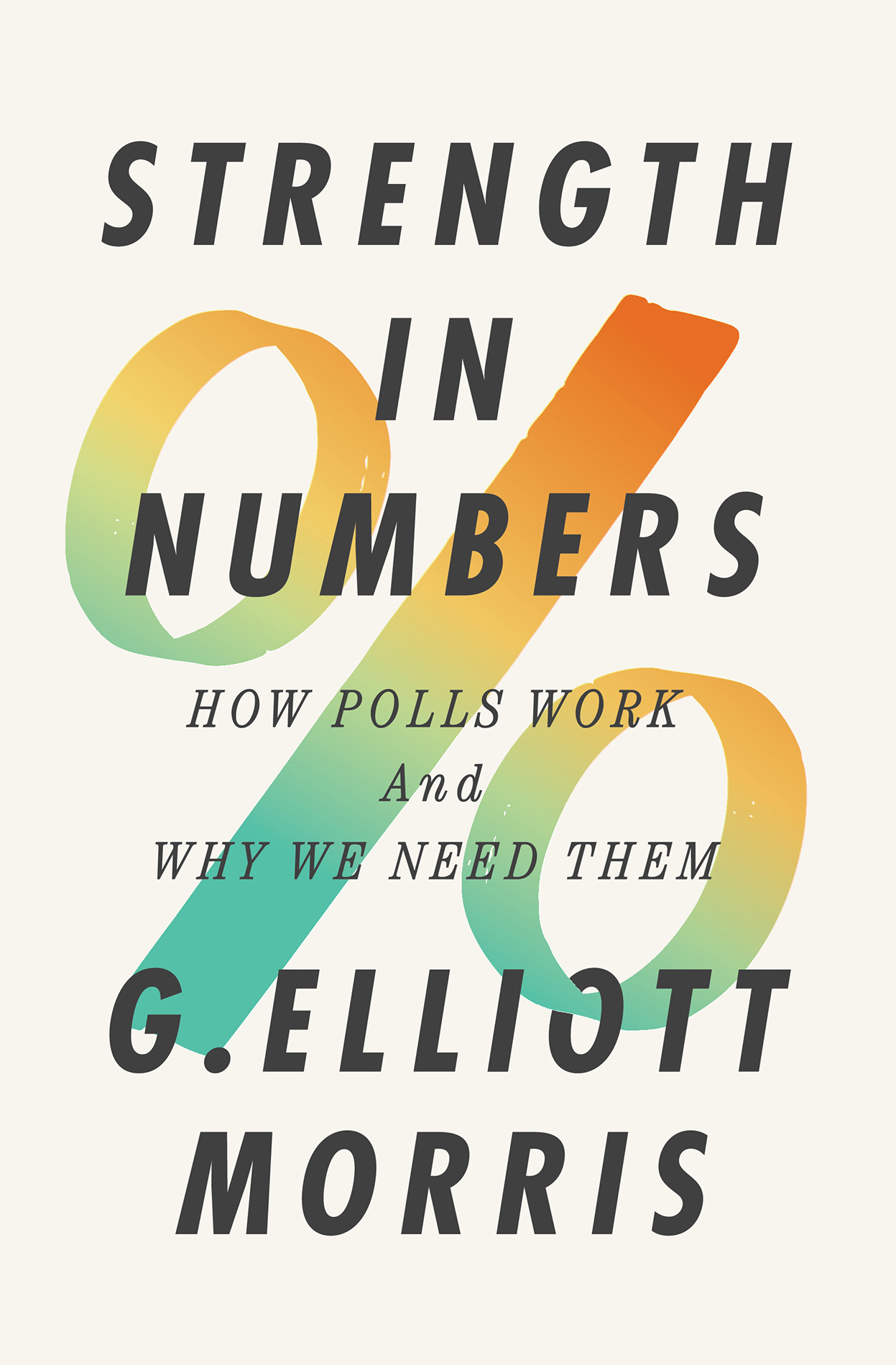

G. Elliott Morris - Strength in Numbers: How Polls Work and Why We Need Them

Here you can read online G. Elliott Morris - Strength in Numbers: How Polls Work and Why We Need Them full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2022, publisher: Norton, genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Strength in Numbers: How Polls Work and Why We Need Them

- Author:

- Publisher:Norton

- Genre:

- Year:2022

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Strength in Numbers: How Polls Work and Why We Need Them: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Strength in Numbers: How Polls Work and Why We Need Them" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Strength in Numbers: How Polls Work and Why We Need Them — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Strength in Numbers: How Polls Work and Why We Need Them" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

STRENGTH

IN NUMBERS

How Polls Work and

Why We Need Them

G. ELLIOTT MORRIS

W.W. NORTON & COMPANY

Independent Publishers Since 1923

Did you, too, O friend, suppose democracy was only for elections, for politics, and for a party name? I say democracy is only of use there that it may pass on and come to its flower and fruit in manners, in the highest forms of interaction between people, and their beliefsin religion, literature, colleges and schoolsdemocracy in all public and private life.

WALT WHITMAN, DEMOCRATIC VISTAS, 1871

I f you have heard anything about public opinion polling, it is probably about the industrys failures. The popular retellings of history hold that polls were wrong in their first major test in 1948, when George Gallup and other pollsters declared that incumbent president Harry Truman would lose to Thomas Dewey (in reality, Dewey didnt even come close), and that they have been wrong many times since. Take the results of the 2016 election. On average, polls predicted that Hillary Clinton would win the popular vote by three or four percentage points, and the Electoral College by over 100 votes. A new generation of data-driven polling experts gave forecasts with precise, mathematical confidence in her victory. But she lost in five key states where the polls consistently had her leading, and only wound up winning the popular vote by two points. The press and the public derided polls, and the pollsters, as inaccurate, misleading, and increasingly irrelevant.

The 2020 election was supposed to be the year that polls came back. Pollsters had learned from their mistakes and fixedor so some saidthe methodological problems that caused them to underestimate the number of Donald Trumps supporters in the electorate. Statistical forecasting models predicted a landslide victory for Joe Biden. Instead, the election was so razor-thin in several states, and ballot-counting so slow due to a surge in mail-in voting and other disruptions caused by the covid-19 pandemic, that the contest wasnt called by major media networks for four days. The official post-election analysis from the American Association for Public Opinion Research (AAPOR), the United States association of pollsters, said the miss constituted the industrys worst performance since 1980.

It looks like the polls, despite nearly a century of trial, error, scientific innovation, and constant promises of improvement, are just hopelessly broken. Right?

Perhaps not.

A PROBLEM OF POLLING, AND OF POLL-WATCHING

We are not just misreading the polls, but also missing their larger promise for our politics. On the first and more narrow count, the evidence shows us that public opinion surveys (which I use interchangeably with polls throughout this book to refer to questionnaires eliciting responses from a group of people) are not capable of providing laser-like predictions of election outcomes. Rather than suggesting a surefire loss for Donald Trump in 2016, the polling data, if analyzed properly, suggested that there was a much higher chance of his victory than most reporters and television news pundits thought. Instead of relying too heavily on these polls, the media may have erred by not relying on them enoughand by incorrectly interpreting the polling data when it did. More than anything, the media and public believed in polls too much and in the wrong ways. And many repeated these mistakes in 2020.

In fact, polls are only a tad worse on average than they have been historicallyand much better than the forecasts generated during the industrys infancy. At a conference at the University of Iowa in 1949, George Gallup, the founding figure in modern American polling, reported that the major pollsters had issued 446 forecasts of candidates vote shares in elections covering the preceding fourteen years. Those predictions missed each partys vote share by an average of four percentage pointseight points when expressed as the miss on the winning candidates margin, as it is commonly expressed todaya fact that Gallup said marveled him. Given the complexity of human behavior and the number of variables that can impact an election outcome, he said, it was quite impressive that polls could come so close. These days, national polls miss the winning partys vote share an average of just one or two points in most elections. Even in 2020, they were only off by two and a half. Few other indicators have such a record of accuracy in measuring public opinion.

In 2018, the political scientists Will Jennings and Christopher Wlezien performed a study similar to Gallups, but across a much broader range. They analyzed thousands of polls taken during 220 different elections across 32 countries from 1942 to 2017. Comparing the pre-election snapshots in these polls to the actual results of the election, they found that polls worldwide have not gotten less accurate over time. Rather, a longer view suggests that the recent blips experienced by the US polling industry are within the normal bounds of historical errors. If anything, Jennings and Wlezien write, polling errors are getting smaller on average.... [While] claims about the demise of pre-election polling have become common in recent times, we find little basis to support them. Though the polls in 2020 were more biased than at any point in the past twenty years, they were better than they were ninety years ago.

It turns out, then, that polling has gotten a whole lot better over time. Its just hard for readers and reporters to see how, and where.

First and foremost, polls suffer from the problem that most people expect too much of them. This is not their fault; most citizens have been misled into believing that surveys are more like an assured statistical calculation than a rough estimate, such as a weather forecast; told that theres a 40% chance of rain, no one should be shocked that theyre caught in a sudden downpour. Instead of calling winners and losers in a binary fashion (proclaiming that Clinton will win and Trump will lose in 2016, for example), polls calculate a range of possibilities for any given percentage (for example, saying that Clinton is favored to beat Trump, but she could just as easily win by five percentage points as lose by one).

Take a poll conducted by ABC News and the Washington Post in Wisconsin before the 2020 election. The survey suggested that Joe Biden, Donald Trumps Democratic rival, was 17 percentage points ahead of the incumbent president; 57% of the Wisconsin likely voters in their sample said they would support Biden, versus 40% for Trump. The news organizations reported that the margin of error for the poll was 4 percentage points for each candidates vote share, meaning Joe Biden could be up by as much as 25 or as little as 9 points. After all the votes were tallied, Biden beat Trump among Wisconsinites by less than a percentage point, making the ABC/Washington Post poll 16 points off in the enda result way outside the margin of error.

The margin of error is what pollsters call this range of possible outcomes. It provides critical information for consumers of political polls. It tells us how confident we can be in the polls finding; how far away its estimates could be from reality purely because of random flukes in the way it was conducted.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Strength in Numbers: How Polls Work and Why We Need Them»

Look at similar books to Strength in Numbers: How Polls Work and Why We Need Them. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Strength in Numbers: How Polls Work and Why We Need Them and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.