I have been working on this book for a rather long time, and Im grateful to many people for their generous help. Thanks go in particular to Ed Miliband, Patrick Legals, Olivier Borraz, Chris Howell, Alan Finlayson, Magnus Ryner, Geoff Eley, Peter Hall, Andrew Martin, Jonas Pontusson, Andrew Scott, Mary Hilson, Victor Perez Diaz, Bo Rothstein, and Joakim Palme. I would also like to thank the Swedish Institute for Futures Studies and my colleagues for their interest in this book. As I write the last words, my thoughts go to two wonderful people in a beautiful house in Somerville, Massachusetts, who gave me a home during my stay at Harvard: Ann Gallagher and Frank Roselli.

Introduction

In recent years, much attention has been devoted to the repositioning of social democracy known as the Third Way, particularly in its Anglo-Saxon form, but far less to its place in the history of social democracy. The first wave of studies of the Third Way saw it as neoliberal, as a continuation of significant elements of Thatcherism as regards the economy, industrial relations, and social justice. Rather, I suggest, the Third Way draws on fundamental continuities in the social democratic project, continuities that are, however, not unproblematic. In particular, this book explores the Third Ways relationship to the knowledge economy and the way in which the Third Ways understanding of the knowledge economy leads to a reinterpretation of fundamental postulates of social democracy around capitalism.

The knowledge economy has been a central element of the Third Way, almost to the point of being its raison dtre. Just as earlier processes of social democratic revisionism took place around processes of industrial transformation, so the Third Way can be understood as the rearticulation of a set of ideological postulates in relationship to its conception of a new economic and social order. Similar to the way in which Social Democrats in the 1950s and 1960s tried to provide ideological coherence to the industrial economy and the social and cultural changes it brought with it, the Third Way is an ideological project that attempts to establish coherent articulations of the knowledge economy. Some of its articulations are indeed strikingly similar to social democracys discourses on the need for adaptation to the industrial economy during the Wilson era in the United Kingdom and the Erlander years in Sweden. Since the mid-1990s, the notion of the knowledge economy has occupied a similar function in social democratic discourse, as the cornerstone of a modernization narrative around information technology, education and lifelong learning, innovation, and entrepreneurship. Where Social Democrats in the postwar period saw the industrial economy as the promise of an affluence that would lead away from class conflict and poverty, the Third Way saw the knowledge economy as a new stage of capitalism that promised prosperity for all. Moreover, the knowledge economy provided a new progressive narrative around questions of social justicebecause social exclusion and the unequal distribution of opportunity are understood as problems for the development of the human capital that is at a premium in the new economy. The knowledge economy seemed to give a new role to the social democratic state for the creation of value, by investing in learning, education, and information technologythe drivers of prosperity in the new economy. Thus it was seen, by a nascent new center Left, as offering a way out of the neoliberal there is no such thing as society while also providing a reason for breaking with the legacies of Fordism and the mechanistic notions of change of the old Left.

The knowledge economy concerns core issues in social democracys understanding of contemporary capitalismthe creation of value and its distribution, the role of markets and the balance between public and private, the balance between labor and capital, the nature of need and want, the role of social justice, the dream of equality. Indeed, the knowledge economy has new implications for age-old social democratic questions of class, exploitation, and emancipation. To the British, then Chancellor of the Exchequer Gordon Brown, in texts from the mid-1990s when New Labour was taking shape, the knowledge economy was an opportunity economics, a new economic egalitarianism that was truly dependent on exploiting the potential of all. Peoples potential was the driving force of the modern economy, and it was the capacity to enhance the value of labor through education and learning that made a modern economy succeed or fail. The challenge to social democratic politics, then, was to ensure labour can use capital to the benefit of all, rather than let capital exploit labor for the benefit of the few. To Brown, this was the point of departure for a new relationship between capital and labour. The knowledge economy signified the final reversal of Marxs power relationship between labor and capital as the skills revolution made capital a mere commodity and put labor in control of the production of value. Hence, the knowledge economy was the promise of socialism.

The important conclusion that we reach is that the Lefts century-old casethat we must enhance the value of labor as the key to economic prosperityis now realizable in the modern economy. If this analysis is right, socialist analysis fits the economic facts of the 1990s more closely than those of the 1890s.

This analysis of a new balance of power between labor and capital stemmed from the idea, inspired by endogenous growth theory, that because knowledge is a kind of capital located within the worker, it also makes workers the owners of their capital and no longer subject to other logics of capital. This is a mindboggling suggestion to socialist thinking. If capital is within us, then how can it exploit us? And if, as Brown suggested, capital is no longer an exploiting force but a force that, in the hands of a Labour government, works for the emancipation of labor, then what is capitalism?

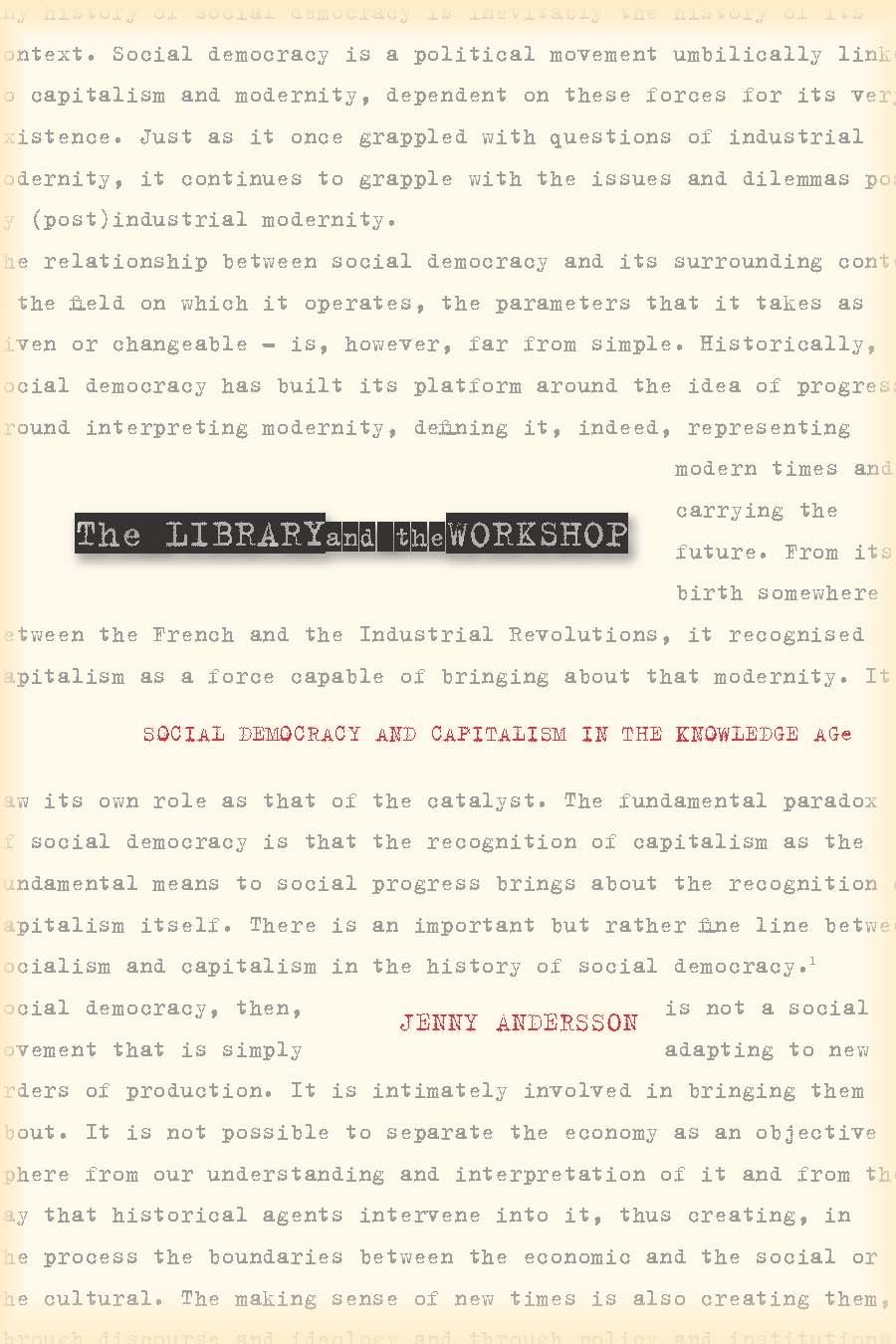

This book explores the way that social democracy makes sense of a new economic and social order based on knowledge. In particular, it points to the different interpretations of the knowledge economy and the knowledge society that exist within Third Way discourse, through an analysis of the different interpretations of a knowledge age of New Labour and the Swedish Social Democratic Party, SAP ( socialdemokraterna ). These differences, the book argues, can be brought back to different definitions of what kind of good knowledge is, how knowledge acts as an economic and social resource, and what that means in terms of economy and society, individuals and politics. To the SAP, knowledge is a democratic, public good that should be created and redistributed on the basis of universalism. Its discourse on the knowledge economy is highly egalitarian, drawing on ideological legacies from the universal welfare state and the partys historic project, the Peoples Home. To quote the Swedish slogan, knowledge grows the more we share it. Key metaphors used in party rhetoric to describe the knowledge economy have been the library or the study circle, both of which draw on the idea of knowledge as produced and distributed on the basis of solidarity and also allude to central elements in party historythe public libraries and study circles that laid the foundation for worker education in the nineteenth century. New Labour, in contrast, spoke in the 1990s of the knowledge economy as the chance for Britain to rise again, as the electronic workshop of the world. To New Labour, knowledge is a competitive commodity and an individual good, to be bartered and sold on the markets of the knowledge economy.