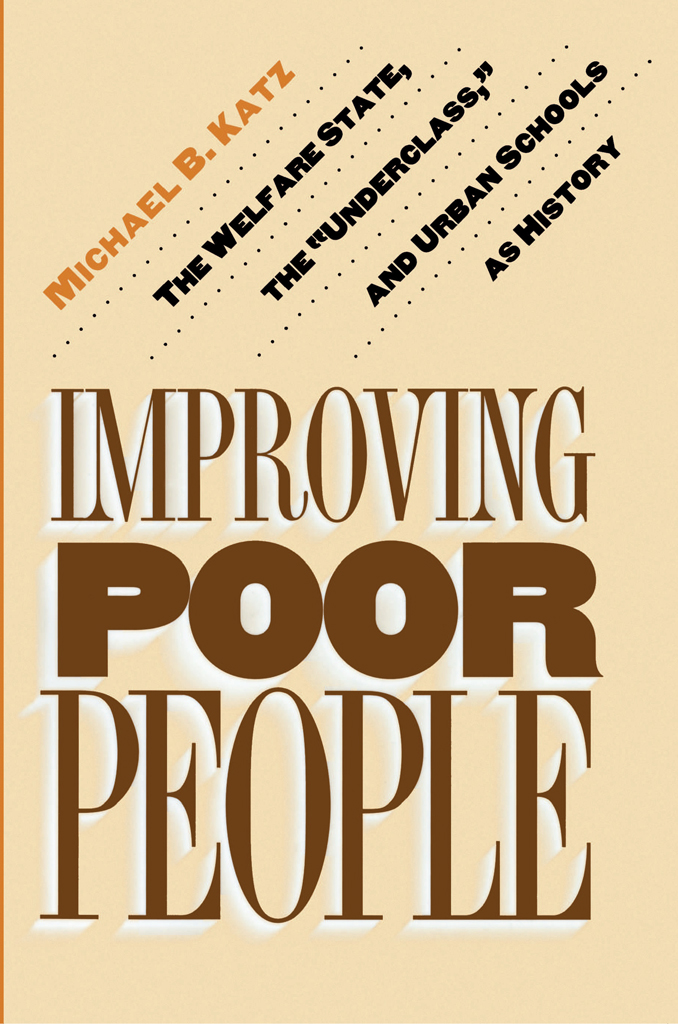

Michael B. Katz - Improving Poor People

Here you can read online Michael B. Katz - Improving Poor People full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2022, publisher: Princeton UP, genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Improving Poor People

- Author:

- Publisher:Princeton UP

- Genre:

- Year:2022

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Improving Poor People: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Improving Poor People" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Improving Poor People — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Improving Poor People" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Improving Poor People

Improving Poor People

THE WELFARE STATE, THE "UNDERCLASS," AND URBAN SCHOOLS AS HISTORY

Michael B. Katz

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON, NEW JERSEY

Copyright 1995 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street,

Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, Chichester, West Sussex

All Rights Reserved

Katz, Michael B., 1939

Improving poor people : the welfare state, the "underclass," and urban schools as history / Michael B. Katz

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-691-02994-6

ISBN 0-691- 01605-4 (pbk.)

1. Public welfareUnited StatesHistory. 2. Urban poorUnited StatesHistory. 3. Urban schools United StatesHistory. 4. Social history. 5. Social policy. I. Title.

HV91.K348 1995

362.5'0973dc20 94-31111

eISBN: 978-1-400-82170-9

R0

For my graduate students

PAST AND PRESENT

Acknowledgments

THIS BOOK draws on almost thirty years of work. In that time I have acquired many intellectual and personal debts. Here, I will acknowledge only some of the proximate ones immediately relevant to this book.

draws on my earlier work on the history of welfare. A somewhat different version was written for a series of conferences on comparative welfare history held at the Werner Reimers Stiftung in Bad Homburg, Germany, which provided generous support, and will be published in a book that I have coedited with Christoph Sachsse, The Mixed Economy of Welfare: Private/Public Relations in England, Germany, and the United States from the 1870s to the 1930s. I want to thank both the Stiftung and the participants in the conference for their helpful comments.

An early version of , which draws on my work on the intellectual history of responses to poverty, was written for the centennial of the Henry Street Settlement in New York. I appreciate the honor conferred by the invitation to lecture at the centennial celebration of an institution with such a rich legacy. My work on poverty was immeasurably enriched by my participation as project archivist in the work of the Social Science Research Council's Committee for Research on the Urban Underclass, and I especially want to thank the committee's excellent staffMartha Gephart, Robert Pearson, Raquel Ovryn Rivera, Alice O'Connorfor their courtesy and for the education they provided.

A portion of was published in Teachers College Record (fall 1992) as "Chicago School Reform as History" and is used with the permission of the journal. The chapter also includes adaptations of earlier essays on the origins of public education. My work on Chicago school reform has been conducted in collaboration with two marvelous and creative colleagues, Michelle Fine and Elaine Simon, and my ideas on the subject derive in large part from our work together and from conversations with them. A portion of the chapter adapts some of our article in Catalyst, the journal of Chicago school reform. Our work started during my year as a Visiting Fellow at the Russell Sage Foundation, which provided the time, encouragement, and stimulation to launch the project. The project has been supported generously by the Spencer Foundation. In Chicago, many people have shown us great courtesy, answering our endless questions, providing background material, giving us precious time. Entering the educational reform community there has been one of the unexpected and great joys of the project.

began as a working paper for the Russell Sage Foundation. My debt to the Foundation, especially its president, Eric Wanner, is very great. A somewhat different version was published in Arnold R. Hirsch and Raymond A. Mohl, eds., Urban Policy in Twentieth-Century America (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 1993) and is used with the permission of the press. A grant from the Research Foundation of the University of Pennsylvania made possible the microfilming of the case records on which the discussion is based.

Three people read the introduction to this book and offered detailed, constructive advice when I was floundering with its organization and content. My gratitude toward them is great. They are Michael Frisch, Viviana Zelizer, and Mike Rose. Mike Rose's wonderful book, Lives on the Boundary, gave me the inspiration and courage to try to mix a bit of autobiography with more conventional writing about history. I also want to thank the two readers of this manuscript for Princeton University Press for their constructive, insightful comments. The editorial staff of Princeton University Press once again has been a joy to work with. My thanks go especially to Lauren Osborne and Beth Gianfagna. Cindy Crumrine has again proved a model copy editor.

During nearly thirty years of teaching, I have had the extraordinary fortune to work with a succession of exceptional graduate students. They have been stimulating and enjoyable intellectual companions, and I always have learned from them. Some of them have become my good friends. This book has a subtext directed to them and, I hope, their successors.

The idea for this book occurred to me in the serenity of Clioquossia in Oquossoc, Maine, where I did most of the work of revising the essays that compose it and writing the introduction. As always, I appreciate the support of friends and neighbors there as well as of my family, especially my wife, Edda, and youngest daughter, Sarah, on whom the preoccupation that accompanies writing takes the greatest toll.

Improving Poor People

Introduction

THERE ARE places where history feels irrelevant, and America's inner cities are among them. Those historians engaged with the problems of their time live, always, with an unresolved tension between activism and scholarship; they are forced on the defense by practitioners of contemporary social science and policy research, whose relentless pres-entism views historians as of little use other than as entertainment. Instead of advancing social reform, do historians, in fact, distract attention from children killing each other, jobless men, homeless families, failing institutions, and crumbling infrastructure? Perhaps historians who care about the future of American cities and their people should throw away their note cards, leave their libraries and archives, and work for a frontline social agency or in community economic development. Would historians committed to social reconstruction give more to the causes they champion with degrees in social work or public policy or as public interest lawyers?

Since the early 1960s, I have lived with these questions and with the tension between activism and scholarship, which I have tried to mediate with research on a number of questions about American social institutions, public policy, and reform. Why have American governments proved unable to redesign a welfare system that satisfies anyone? Why has public policy proved unable to eradicate poverty and prevent the deterioration of major cities? What strategies have helped poor people survive the poverty endemic to urban history? How did urban schools become unresponsive bureaucracies that fail to educate most of their students? Are there fresh, constructive ways to think about welfare, poverty, and public education? Do any hopeful examples exist?

Because they traced extreme poverty to drink, laziness, and other forms of bad behavior, many nineteenth-century reformers tried to use public policy and philanthropy to improve the character of poor people rather than to attack the material sources of their misery. Reformers emphasized individual regeneration through evangelical religion, temperance legislation, punitive conditions for relief, family breakup, and institutionalization. Of course, as a reform strategy, improving poor people did not end with the nineteenth or early-twentieth centuries, as almost any contemporary discussion of "welfare reform" reveals. Indeed, in the 1990s, discussions of inner-city poverty invoke an "underclass," defined primarily by bad behavior, not by poverty, and deemed to be more in need of improvement than cash.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Improving Poor People»

Look at similar books to Improving Poor People. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Improving Poor People and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.