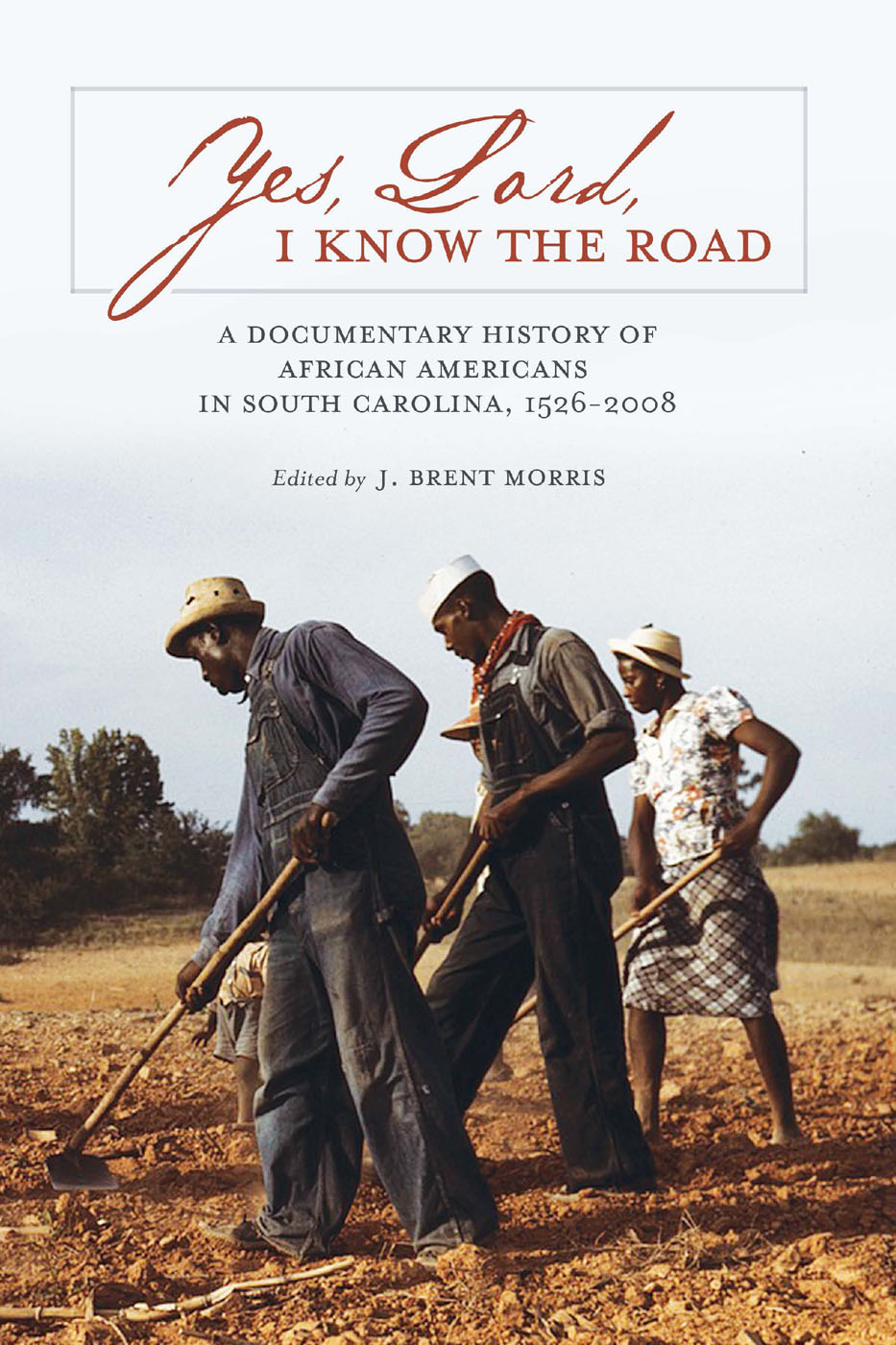

YES, LORD, I KNOW THE ROAD

Yes, Lord ,

I KNOW THE ROAD

A DOCUMENTARY HISTORY OF

AFRICAN AMERICANS IN

SOUTH CAROLINA

15262008

Edited by J. BRENT MORRIS

THE UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH CAROLINA PRESS

2017 University of South Carolina

Published by the University of South Carolina Press

Columbia, South Carolina 29208

www.sc.edu/uscpress

26 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Morris, J. Brent, editor.

Title: Yes, Lord, I know the road : a documentary history of African Americans in South Carolina, 15262008 / edited by J. Brent Morris.

Description: Columbia, South Carolina : University of South Carolina Press, [2017] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016047778 (print) | LCCN 2016049459 (ebook) | ISBN 9781611177305 (hardcover : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781611177312 (pbk. : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781611177329 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: African AmericansSouth CarolinaHistorySources. Classification: LCC E185.93.S7 Y47 2017 (print) | LCC E185.93.S7 (ebook) | DDC 975.7/00496073dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016047778

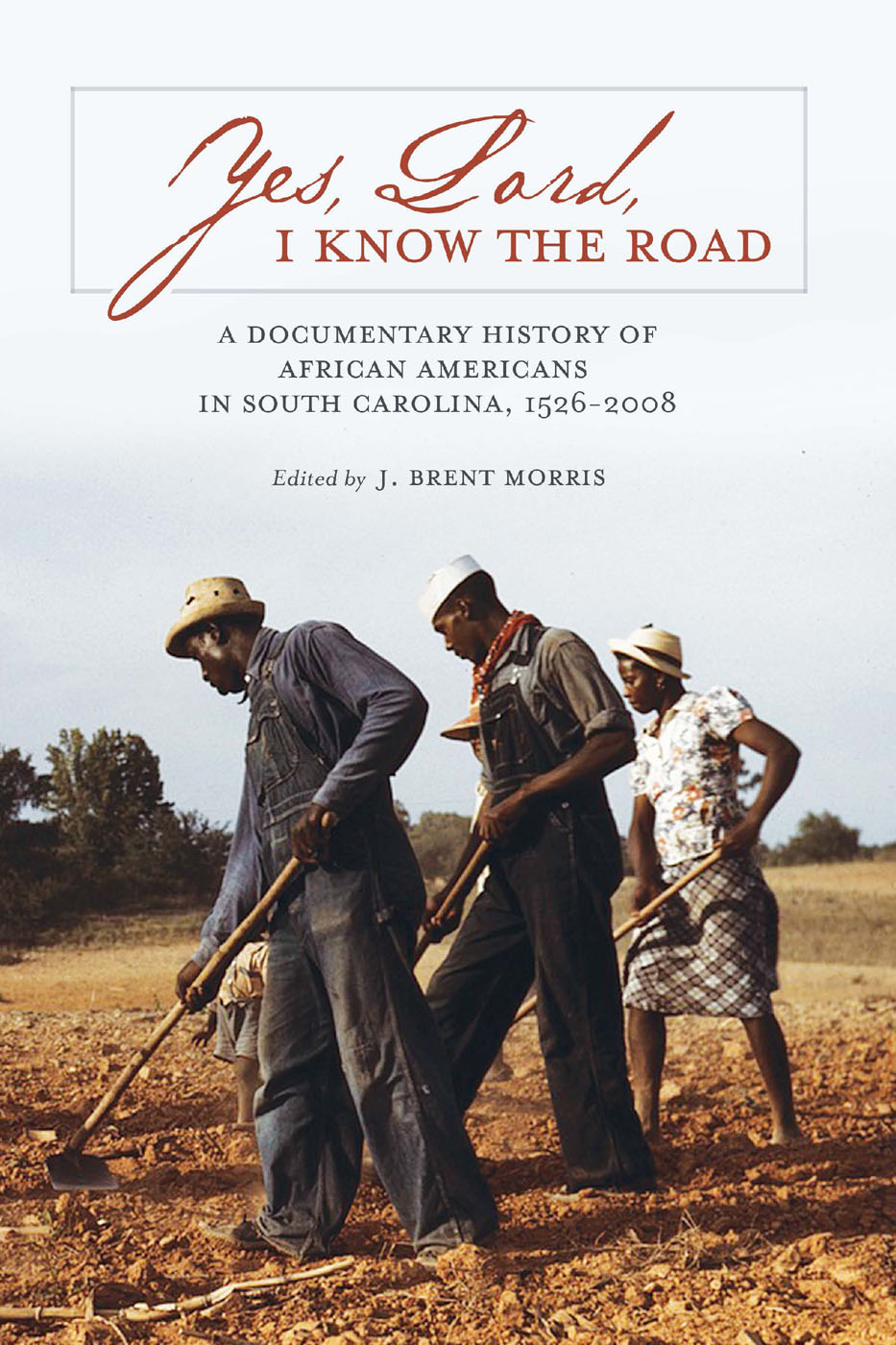

Front cover photograph courtesy of the Library of Congress

Sheep, sheep, do you know the road?

Yes, Lord, I know the road.

Sheep, sheep, do you know the road?

Yes my Lord, I know the road

Sea Islands spiritual

CONTENTS

Daniel C. Littlefield

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

Marching On!The Fifty-fifth Massachusetts

Colored Regiment singing John Browns March in the streets of Charleston

FOREWORD

This documentary narrative of African Americans in South Carolina covers the broad sweep of the states history from early Spanish explorations to the modern political and social activities of people of African descent. It promises to be a boon for students, teachers, and the general public interested in the unique background of a small, complex, and fascinating region. The documents are extraordinary and well chosen. They reveal, for example, that less than thirty-five years after Christopher Columbuss first voyage, Spanish explorers incited here perhaps the earliest rebellion of enslaved Africans on the North American coast and one of the earliest anywhere in the New World. They contradict any notion that armed resistance was practically unknown among peoples brought unwillingly to labor for Europeans in North America (in contrast to what is conceded for enslaved Africans elsewhere in America) or that the northern mainland was in any way exempt from the prevailing cultural, political, and social currents that affected the meeting of black and white people everywhere during their settlement in America and during and after the development of plantation economies. There was cooperation and conflict, personal affection and abiding antagonism. No other time or place offers better examples of these commonalities than South Carolina, particularly during the colonial period. Here captive south-central Africans staged the largest slave rebellion in Englands continental colonies, featuring a prominent ethnic dimension, and here planters evinced a more open toleration for interracial dalliance than is often acknowledged for the English main. But the intriguing features of this province did not end when it rejected British hegemony. Whether in religion or revolution, this small state offers extraordinary illustrations of African American agency (to evoke a convenient term too easily used) that discredits the idea that African peoples lacked intelligence or initiative and leads to the suggestion that those in South Carolina may have had a disproportionate influence on American society and culture in relationship to the size of the region where they lived. The state was distinctive in the dimension of its African population and in the nature of its African-influenced culture. Moreover, these features extended beyond the colonial period and continue to affect Carolina culture and society in the modern age. There are examples here of the context within which African Americans operated as well as the communities they formed and the activities they adopted to overcome their obstacles.

Professor Morris provides a solid introduction that puts these documents into perspective. Whether considering abortive Spanish settlements, English colonial developments, the Lowcountrys differentiated labor system, the various staples cultivated, or the tragedy of war and the shortcomings of Reconstruction, he judiciously fills gaps between the documents. One advantage of his outlook is that he does not treat this story in a vacuum but situates the state and the African Americans who inhabit it within a larger Atlantic world and the national scene. He notes the regime of white supremacy and its collapse, the civil rights movement, the ways in which South Carolina handled desegregation and the reasons behind that policy, the return of African Americans to political influence, and events in the twenty-first century during the Age of Obama. Indeed, his essay is an admirable recounting in capsule form of African Americans in South Carolinas history and is a useful short reference. Students as well as the public will find here a handy tool for their edification.

DANIEL C. LITTLEFIELD

PREFACE AND EDITORIAL NOTES

African Americans were among the first pioneers in the land that eventually became South Carolina, and for most of the nearly five centuries that followed their arrival, men, women, and children of African descent have been a majority of the population there. Until relatively recently, however, their historytheir vital role in the development of the colony, state, and nationhas either been misrepresented or neglected entirely. Fortunately, historians writing during and after the civil rights movement of the mid-twentieth century have devoted considerable attention to the dynamic story of black South Carolinians. Copious and often brilliant scholarship has highlighted African American history and culture in the state from the sixteenth through the twenty-first centuries in local, regional, national, and global contexts.

Still, this flurry of scholarly activity has not produced a comprehensive synthetic history of African Americans and South Carolina. This work is not intended to satisfy that need, although it is the first substantial overview of that story. Nor does it endeavor to evaluate the diverse historiography of the past few decades. Rather, Yes, Lord, I Know the Road offers, within the limits of approximately 100,000 words, a synopsis of five centuries of rich history to guide scholars until someone takes on the monumental challenge of producing that long-awaited monograph. In the introduction, details are sacrificed for the sake of concision, and much that truly deserves extended analysis is by necessity wrapped into broad generalizations. However, this books most valuable section, the eighty edited documents and images that constitute the bulk of the work, are the true substance of the story. They are, as Herbert Aptheker wrote in the introduction to one of his many documentary readers, the words of participants, of eye-witnesses. These are the words of the very great and the very obscure; these are the words of the mass. This is how they felt; this is what they saw; this is what they wanted.

This book invites readers to work with these component pieces of history and consider how they inform the bigger story. Reading narrative alongside the sources black Carolinians left behind brings life and relevancy to the past. We more fully empathize with the enslaved woman working in the muck of a rice field as the summer sun beats down on her back and mosquitoes swarm about her head. We appreciate the determination of a maroon, defiant and diligent, setting up his camp deep in a swamp. We hear the cadence of a Gullah sermon, the percussive echo of clapping, and the counter-clockwise shuffling of feet. We feel the bright spotlights front and center at a national political convention. Many of these source documents are previously unpublished; many others have been long out of print. It is my hope that the collection will spark new conversations, inspire fresh questions, and point new ways for historians to pursue innovative scholarly work.

Next page