THE

DORR

WAR

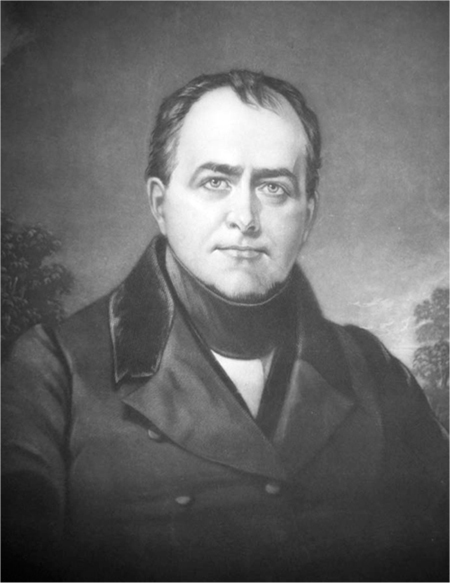

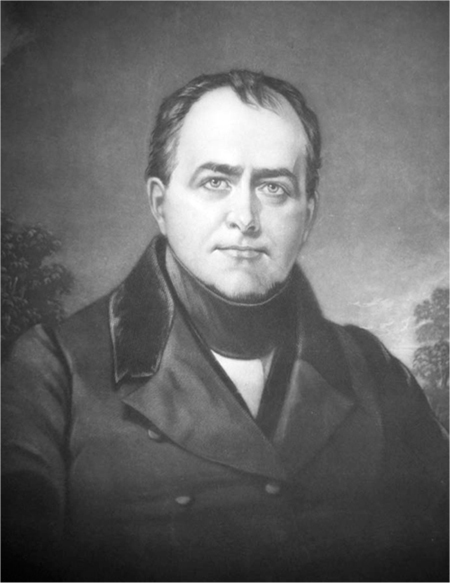

Thomas Wilson Dorr (18041854), the peoples governor. Courtesy of Larry De Petrillo.

THE

DORR

WAR

T REASON ,

R EBELLION

&

THE F IGHT

FOR R EFORM IN

R HODE I SLAND

R ORY R AVEN

Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC 29403

www.historypress.net

Copyright 2010 by Rory Raven

All rights reserved

Cover images courtesy of Russ Desimone and Brown University.

First published 2010

e-book edition 2011

ISBN 978.1.61423.104.2

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Raven, Rory.

The Dorr War : treason, rebellion and the fight for reform in Rhode Island / Rory Raven.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

print edition ISBN 978-1-59629-959-7

1. Dorr Rebellion, 1842. 2. Dorr, Thomas Wilson, 1805-1854. 3. Rhode Island--Politics and government--1775-1865. 4. Suffrage--Rhode Island--History--19th century. I. Title.

F83.4.R38 2010

974.503--dc22

2010039224

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

Dedicated to the memory of

Thomas Wilson Dorr

A forgotten hero and

a man ahead of his time

Whoever writes the history of these things, if he has an impartial temper, a quick eye for the ludicrous, and the power to see the cause of things in the things themselves, will furnish a most amusing and instructive chapter in the history of the times.

Abraham Payne, December 27, 1854

C ONTENTS

A CKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Nobody writes a book on his own. The following people were helpful in either tangible or ineffable ways. Many thanks to:

My wife, Judith, who puts up with a lot; Alison Bundy of the John Hay Library at Brown University, for her patience with endless Oh, just one more thing requests; the lovely Hannah Cassilly, my handler at The History Press; Erik J. Chaput, for discovering Dorrs Massachusetts arrest warrant; Dan Ciora, for untangling legal questions; Cirkestra, Emperor Nortons Stationary Marching Band, Jesca Hoop, Steve Martin and Carrie Rodriguez for supplying the writing soundtrack; Russ DeSimone, collector and expert on the Dorr War, who could have written this little book with one hand tied behind his back; the ever-supportive Larry De Petrillo, who has a picture of everything; Paul DiFilippo, for his enthusiasm from early on in the project; Dixie, for occasionally shutting up and letting me think; Jill Jann, behind me every step of the way; Edna Kent, for her time and information; John McNiff, for his expertise in antique ordnance; various members of the Providence Public Librarys reference department, who displayed conspicuous valor, patience and general splendidness; Will Schaff, for help once again beating images into submission and continuing to be a good friend; Elizabeth Wayland-Seal, for kind encouragement when I needed it; Wilkie and Bellamy, because I havent thanked them yet; Amara Willey, who long ago advised me to take on things I thought were slightly over my head so I could work up to them; and you, for being someone who reads thank-yous.

1

T HE C HARTER

A band of armed men marched cautiously through the dark streets of Providence on a hot summer night. They wore no uniforms but the workaday clothes of laborers, millworkers and mechanicsmen who worked with their hands and their backs. They seemed to be armed with whatever came to hand; some had rifles or pistols, but others carried improvised clubs or nothing at all. Some men at the rear laboriously towed a pair of antique cannon. The little army, about three hundred strong, was led by a portly man who limped along, sword in hand, urging his men forward. Calling them a ragtag band would almost have been a compliment.

They made their way through the streets of a residential neighborhood, houses looming up on either side of them. This was a good neighborhood, and these were houses almost none of these men could afford. At length, they reached their destination, an area of several acres worth of open, grassy ground. Their target, an arsenal and the weapons stockpiled within, stood out in the humid fog a short distance away. The men fanned out and took up their positions, and the cannon were wheeled into place, loaded and aimed.

With a nod from their leader, one man dashed across the open ground to bang on the buildings stout iron door, demanding the garrisons surrender in the name of the governor. A moment later, he ran back across to the attackers, shaking his head as he went. They had their answer.

Barking final orders as his men scrambled chaotically, their leaderGovernor Thomas Wilson Dorr, a Harvard-educated lawyer and member of one of the states oldest patrician familiesmust have wondered how it had come to this, how he had found himself leading a dead-of-night attack on an arsenal.

He turned to the cannon crew and gave the order to fire.

The battle lines in what came to be known as the Dorr War had been drawn almost two centuries before and an ocean away. On July 8, 1663, King Charles II, newly ascended to the English throne, granted the colony of Rhode Island a royal charter.

Roger Williams, a Puritan radical and the Rhode Island colonys founder, had previously traveled to England to obtain a royal patent for his fledgling colony in the 1640s. Arriving during the chaos of the English Civil War, he was unable to meet with King Charles I, who was too busy losing to Oliver Cromwell, but he did manage to see the powerful Parliamentary commissioners for plantations. Williamss friendships with such Puritan luminaries as John Milton and even Cromwell himself probably opened some doors that might have otherwise remained closed. The patent the commissioners granted served as official recognition of Providence Plantation as an English colony, guaranteeing colonists full power and authority to rule themselves and such others as shall hereafter inhabit within part of the said tract of land, by such form of civil government as by voluntary consent of all or the greater part of them. The king himself may not have issued the patent, but it was the next best thing.

Cromwell died in 1658. His Protectorate government collapsed, and the monarchy was restored when King Charles II took the throne on May 29, 1660, his thirtieth birthday. He and his new Cavalier Parliament quickly annulled the actions of the previous parliament, ordered the deaths of some of those who had deposed and executed his father, Charles I, and had Cromwells body exhumed, drawn and quartered just for good measure.

This caused some concern across the sea in Rhode Island. With Charles II backdating official documents to show he had been crowned in 1649, directly succeeding his father and ignoring a decade of history, it was uncertain whether the new king would recognize the validity of a colonial patent issued before that time. And even if no one in the colony was running around punishing corpses, there was enough strife to go around. Unfortunately, the patent had not clearly delineated the colonys borders, leading to disputes with neighboring Massachusetts and Connecticut, both greedily eyeing the little colonys territory. It seemed wise to acquire a new document from Charles II, definitively establishing Rhode Islands status.

Next page