When Is Free Speech Hate Speech?

Other Books in the At Issue Series

Are Graphic Music Lyrics Harmful?

Banned Books

Bilingual Education

Caffeine

Campus Sexual Violence

Can Diets Be Harmful?

Childhood Obesity

Civil Disobedience

Corporate Corruption

Domestic Terrorism

Environmental Racism

Gender Politics

Guns: Conceal and Carry

The Right to a Living Wage

Trial by Internet

When Is Free Speech Hate Speech?

Martin Gitlin, Book Editor

Published in 2018 by Greenhaven Publishing, LLC

353 3rd Avenue, Suite 255, New York, NY 10010

Copyright 2018 by Greenhaven Publishing, LLC

First Edition

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer.

Articles in Greenhaven Publishing anthologies are often edited for length to meet page requirements. In addition, original titles of these works are changed to clearly present the main thesis and to explicitly indicate the authors opinion. Every effort is made to ensure that Greenhaven Publishing accurately reflects the original intent of the authors. Every effort has been made to trace the owners of the copyrighted material.

Cover image: Ivan Kotliar/Shutterstock.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Gitlin, Marty, editor.

Title: When is free speech hate speech? / Martin Gitlin, book editor.

Description: New York : Greenhaven Publishing, 2018. | Series: At issue | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Audience: Grades 9-12.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017009086| ISBN 9781534500785 (pbk.) | ISBN 9781534500778 (library bound)

Subjects: LCSH: Hate speech--Law and legislation--United States--Juvenile literature. | Freedom of speech--United States--Juvenile literature. | Hate speech--Law and legislation--Juvenile literature.

Classification: LCC KF9345 .W44 2017 | DDC 323.44/30973--dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017009086

Manufactured in the United States of America

Website: http://greenhavenpublishing.com

Contents

Introduction

Where Does Free Speech End and Hate Speech Begin?

Joyce Arthur

Hate Speech and Free Speech Are Not Relatives

Twigg

Harmless Hate? Theres No Such Thing

Jeremy Waldron

Hate Speech Is Risky Business

Devin Foley

Free Speech Seems to Be Selective

Raouf Halaby

Education Depends on Free Speech, Even Hate Speech

Greg Lukianoff

Hate Speech Is Unfitting in a Democracy

Zack Beauchamp

What If Hate Speech Were Criminalized?

Hadewina Snijders and Ruth Shoemaker Wood

Regulating Hate Speech Is Not Productive

Kenan Malik

It Can Be Difficult to Distinguish Fighting Words

David L. Hudson Jr.

There Is No Hate Speech Exception to the First Amendment

Eugene Volokh

Hate Speech Is Harmful, but It Shouldnt Be Legislated

Joyce Arthur and Peter Tatchell

Free Speech Is Essential on College Campuses

Greg Lukianoff

In Defense of Uncomfortable Learning

Alex Morey and Adam Steinbaugh

Censoring Hate Speech Makes Sense

Sean McElwee

Hatred for Hate Speech Is Misplaced

BlackCatte

Lets Make the Punishment Fit the Crime

Michael Lieberman

Organizations to Contact

Bibliography

Index

Introduction

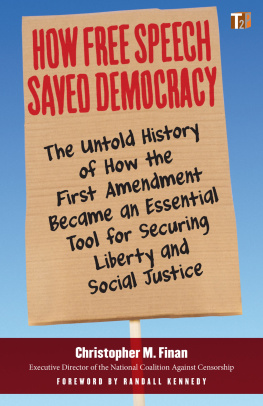

T he First Amendment to the United States Constitution was intended to provide clarity in regard to freedom of speech. The ink-to-paper tenets set forth in 1789 established an unalienable right for all Americans. And it has been embraced ever since as a beacon and one of the guiding principles on which the country was founded.

But thirteen years before the Constitution was written, the Declaration of Independence featured a phrase that had destroyed the possibility of absolutism. It has been proven that unhindered freedom of speech can spur events that prevent others from attaining life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. When freedom of speech is interpreted as freedom to express hate, it is the duty of lawmakers and courts to decide if it infringes upon the ability of an individual or group to indeed live up to the ideals as stated in 1776. The blurring between free speech and hate speech has been debated for more than a century.

Hate speech is defined as words that offend, threaten, or insult based on race, religion, national origin, sexual orientation, disability or other traits that most Americans accept make their country wonderfully diverse. The huge majority of public speeches given even by the most polarizing liberal or conservative in American society are rarely construed as espousing hate. Such utterances are generally reserved by right-wing or religious extremists, many of whom believe in white supremacy or embrace a perverted view of God as hating groups such as Muslims or gays. But where does hate speech end and fighting words begin? And should extremists be allowed to express their views openly in the first place?

The gray area has never been transformed to black or white. Libertarians that claim free speech includes hate speech believe that placing restrictions on one person weakens the rights of all. They might recognize that fighting words a phrase used by the Supreme Court in 1942 to establish a limitation to free speech promotes violence to such a degree that it is a sufficient reason to rein in that right. But they also feel strongly that hate speech should not be restricted by the government unless it directly causes a threat to peace.

An opposite view is embraced by communitarians. They believe that free speech takes a back seat to the security of a community and all its citizens. They reacted with dismay, for instance, when the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) fought for the right of neo-Nazis to march in a predominantly Jewish neighborhood of Skokie, Illinois, in 1977. Their view is that hate speech should not be allowed when it is being spewed by those who seek to prevent individuals or groups from being treated with dignity and respect. Libertarians claim that such restrictions would severely limit free speech and be subject to interpretations of intent that would be impossible to be agreed upon.

The controversy intensified after Donald Trump began his presidential campaign in 2016. His rhetoric and stated views about closing the doors to Muslim refugees, sending illegal immigrants back to Mexico and building a wall to prevent others from entering the country motivated extremists such as white nationalists to rally by his side. It can be argued that Trump had no intention to legitimize those who hate, but the result was an awakening of the free speech/hate speech debate through their words.

History provides arguments on both sides. The wide-open Weimar Republic in Germany of the 1920s and early 1930s promoted unlimited free speech. The result, particularly after World War I and during the depression, was the rise of extremist views that were openly expressed. The most effective speaker during that era was Nazi Party leader Adolf Hitler, who made no secret of his hatred of Jews and Communists, whom he linked together. His hate speeches drove supporters to violently attack perceived enemies of Germany. Hitler, however, banned free speech after taking power in 1933. One could argue that hate speeches that could be perceived as threatening against Hitler and his Fascist followers would have saved the world from the Holocaust and a war that killed at least fifty million people.