Copyright 2021 by Abbe R. Gluck and Charles S. Fuchs

Cover design by Pete Garceau

Cover copyright 2021 by Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

PublicAffairs

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104

www.publicaffairsbooks.com

@Public_Affairs

First Edition: November 2021

Published by PublicAffairs, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The PublicAffairs name and logo is a trademark of the Hachette Book Group.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events.

To find out more, go to www.hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

Editorial production by Christine Marra, Marrathon Production Services. www.marrathoneditorial.org

Set in 12-point Adobe Caslon

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data has been applied for.

ISBNs: 978-1-5417-0061-1 (hardcover), 978-1-5417-0062-8 (e-book)

E3-20211009-JV-NF-ORI

For my wife, Joanna Fuchs, a proud cancer survivor who inspires me and gives me strength every day.

C. S. F.

For my extraordinary mother, Ruth Rubin Gluck, who lost her war far too young, in 1999, but remains with me always.

A. R. G.

When President Richard Nixon entered the White House state dining room just before noon on December 23, 1971, he was greeted by some 137 assembled guests hailing from the most powerful precincts of government, science, industry, and advocacy. They were there to witness the signing of the landmark National Cancer Actthe product of feverish debate and political jockeying extending over decades of committed advocacy. While what would later be called the War on Cancer Act was not the parlance of the day, Nixon set forth a national commitment for the conquest of cancer and reflected that we may look back on this day and this action as being the most significant action taken during this administration.

According to a report submitted to Congress in 1970 by a group of experts tasked with studying the issue, cancer was the number

Looking back today on the fiftieth anniversary of the War, its achievements are clear in the enormous strides that have been made. Although the cancer death rate in the US continued to rise in the twenty years that followed passage of the bill, cancer mortality rates have declined 29 percent since 1991, translating into an estimated 2.9 million fewer cancer deaths than would have occurred if peak rates had persisted. Efforts in cancer prevention, most notably reduction in the use of tobacco products, account for much of the mortality reductions, though recent advances in cancer therapeutics are now also contributing.

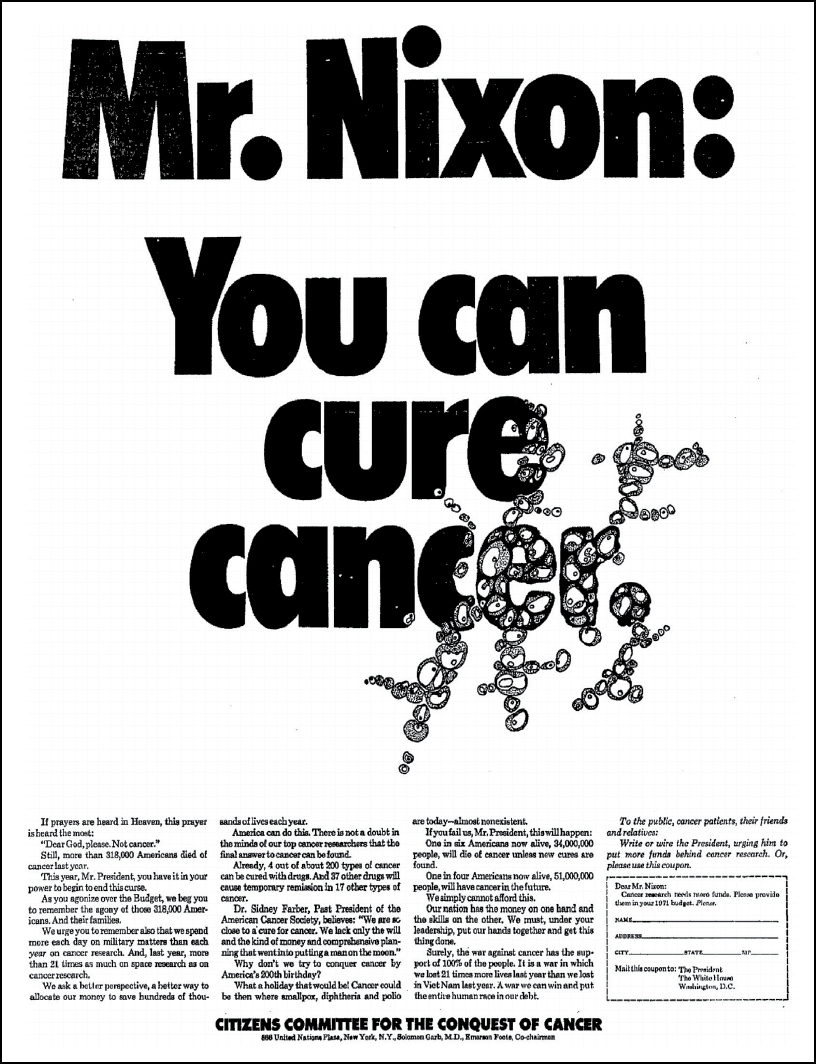

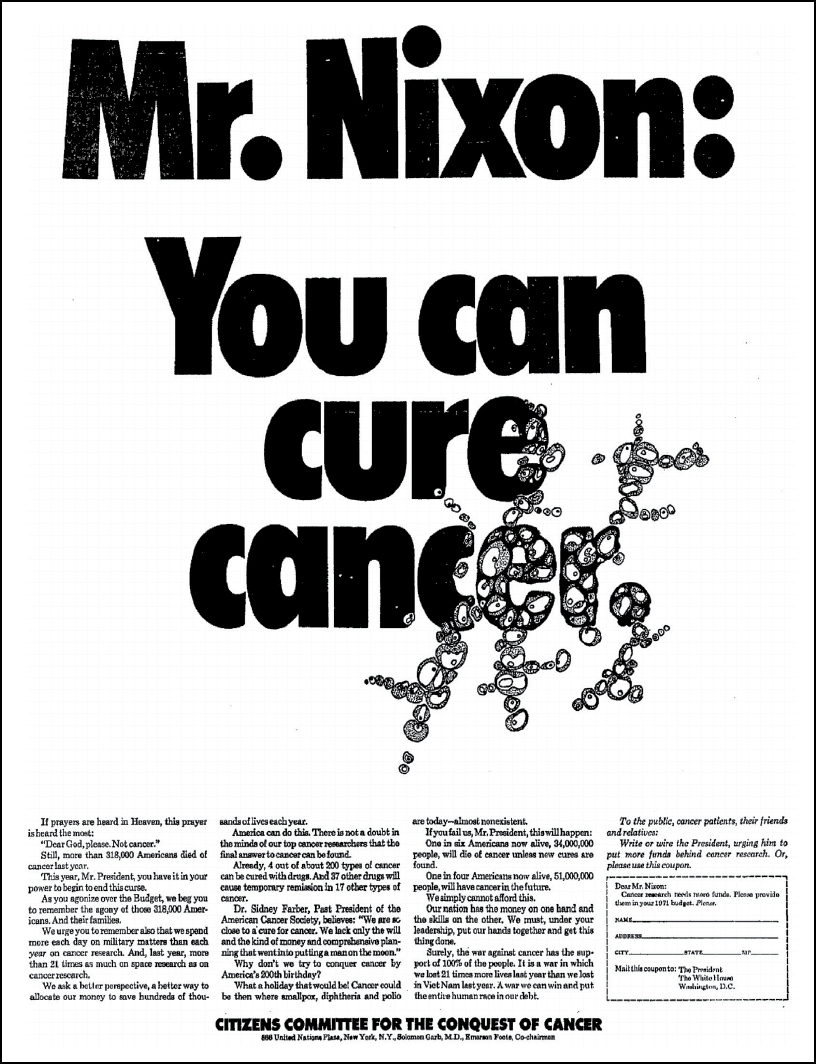

While we celebrate these achievements, we must also recognize the shortfalls. Cancer was not cured by 1976. The mission statement was too simple. And the 1971 law did not go far enough. Senator Ted Kennedy, standing mere feet from Nixon during the signing ceremony, was the chief sponsor of a more ambitious bill that would have created a National Cancer Authorityan independent agency responsible for cancer researchalongside a major expansion in federal funding for research itself. Championed and in many ways crafted by famed cancer advocate Mary Lasker, Kennedys Conquest of Cancer was inspired by the Apollo 11 moon landing. The renowned December 1969 New York Times full-page adMr. Nixon: You Can Cure Cancerquoted Harvards Sidney Farber as saying: We lack only the will and the kind of money and comprehensive planning that went into putting a man on the moon Why dont we try to conquer cancer by Americas 200th birthday? The vision was for cancer to have its own NASAthe first cancer moonshot had arrived, at least as an idea.

But that idea fell short in the House, which forced the compromise legislation enacted in 1971 that expanded the authority of the National Cancer Institute (NCI) but left it under the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The final version of the act was still intended to meet a towering five-year goal, which of course was not met: curing cancer by the nations bicentennial in 1976.

But the War on Cancer might also have gotten ahead of itself. Experts worried at the time that the science of cancer was not sufficiently well understood to even come close to the goals set by the Nixon administration. As Sol Spiegelman, director of Columbia Universitys Institute of Cancer Research, pointedly noted, An all-out effort at this time would be like trying to land a man on the moon without knowing Newtons laws of gravity.

Today, we recognize that cancer is not a single illness to be conquered, but hundreds of different, complex diseases requiring a deep understanding of each entitys unique biology, genetics, clinical characteristics, susceptibility to treatment, and ability to rapidly develop therapeutic resistance. Additionally, the notion of a truly comprehensive nationally run strategy for cancer was never fully realized. The 1971 act envisioned a key role for the federal government: one in which it had to play a centralperhaps the centralrole in confronting cancer in America. This would require not just the power of the pursethrough funding and appropriationsbut all the might of the federal government, bringing to bear public organization, agency action, and presidential leadership.

But subsequent decades of slow, albeit persistent, progress and fragmented policies underscore a simple truth: we still do not have a clear and unified federal governmentled approach that fully harnesses and focuses the vast talent and resources of this nation to tackle the panoply of challenges and steps needed to eliminate cancerthat is, a program that truly lands a man on the moon.

The mission as conceived was not ambitious enough while also being too narrow in critical ways. The idea that a scientific cure was the only goalthe only barrier to eradicating the scourge of the diseasedid not predict the enormous range of cancer as an institution, as Siddhartha Mukherjee so aptly puts it in these pages, and the obligation of any government response to think about the world cancer inhabits more broadly so as to properly address it. The War was not against a single enemy but countless adversariesand not just in the vast number of unique cancer subtypes we understand to exist today. On the battlefield are also the business and economics of cancer, the fragmented and often costly and inefficient regulatory landscape, intolerable problems of health justice and equity, crushing pressures on the everyday practice of cancer medicine, and lack of prevention and attention to public healthall alongside enduring questions about the proper role of our state and federal governments.

This book aims to tackle those issues and open a broader lens onto the War on Cancer. We seek to shift the metaphorto advance a New Deal for Cancer that places the federal government at the center of a whole-of-nation response that recognizes the need to make progress not just on the science of cures but also with respect to the people and institutions that make up the system.