This Land Is My Land

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

Oxford University Press 2020

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Skillen, James R., author.

Title: This land is my land : rebellion in the West / James R. Skillen.

Description: New York, NY : Oxford University Press, [2020] |

Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020006687 | ISBN 9780197500699 (hardback) |

ISBN 9780197500712 (epub) | ISBN 9780197500729 (online)

Subjects: LCSH: Public landsWest (U.S.) |

Land useGovernment policyWest (U.S.) | Civil religionWest (U.S.) |

Government, Resistance toWest (U.S.) | United StatesPolitics and government.

Classification: LCC HD243.W38 S553 2020 | DDC 333.1097809/045dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020006687

For Dave Willis

A defender of wild places who tells this story in a different voice

Contents

This project took three years to complete, and I am grateful for generous support during that time for both research and writing. First and foremost, I am grateful to countless public servants in the Bureau of Land Management, the Forest Service, and the Park Service who provided information about and reflections on their work. I have enormous respect for them and the challenges they face in stewarding the publics land. I am also grateful to the staff at E&E News, the Forest History Society, High Country News, Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility, and the Public Lands Foundation, who all provided essential research materials. And I am grateful for the meticulous work of three research assistants at Calvin University: Olivia den Dulk, Kelly Looman, and Noah Schumerth.

For financial support, I am grateful to Calvin University, which provided a sabbatical leave in the fall of 2017 and an additional research fellowship in the 20182019 academic year. Calvins Sustainability Major Initiative and the Henry Institute for the Study of Christianity and Politics both provided funding for research assistance, and the Calvin Center for Christian Scholarship supported my work in a writing co-op during the summer of 2019.

Finally, I am grateful to a variety of colleagues who discussed the project and provided feedback on parts of the manuscript. Thank you first to Leisl Carr-Childers and James W. Skillen. I am also deeply grateful for discussions at various states of this project with the late John Freemuth and the late John Nagle. Both had a profound influence on federal land stewardship, both shaped my scholarship, and both are missed beyond measure.

The federal government, naturally, had a different view of the situation, since Bundy had been grazing his cattle on federal lands without authorization for twenty years, and a federal court had authorized the cattle roundup. During the week-long standoff, guns were drawn, but no one was killed.

In January 2016, one of Cliven Bundys sons, Ammon, stood in the Safeway parking lot in Burns, Oregon, and shouted to protesters gathered there, Im asking you to follow me and go to the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge, and were gonna make a hard stand.

The media struggled to understand what was going on in Nevada and Oregon. During the Nevada standoff, one British reporter from New York City asked me this: The first question that I and my editor have... Is this really happening? I appreciated his mock incredulity, since the images made it look like a sheriffs posse was still running the West. Other reporters and media personalities expressed shock as well, but for different reasons. Sean Hannity of Fox News and Alex Jones of InfoWars expressed their disbelief that the federal government would send officers to the Bundy ranch in full tactical gear. How could it be, they asked rhetorically, that the United States had devolved into something like Nazi Germany?

How do we make sense of the 2014 standoff in Nevada and the 2016 occupation in Oregon? Did Americans really need to make an armed stand against the federal government? Were the courts, legislatures, and law enforcement agencies so corrupt that they couldnt provide justice? And were the Bundys and their supporters engaged in legitimate political protest and civil disobedience, as Cliven Bundy claimed by comparing himself with Rosa Parks, or were their actions genuine threats to the basic rule of law?

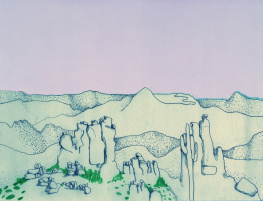

The first step toward understanding what happened is to see these events within the context of a longer story of conflict over federal lands in the American West, particularly conflict between the federal agencies managing roughly half of all land in the eleven western states, as depicted in , and the people who depend on those lands for their livelihood, lifestyle, and culture. The federal government is the de facto land use planner in this region and, as a result, has mediated profound economic and social changes. The Bundys stand in a tradition of conservative westerners struggling to stop or roll back those changes.

Figure 0.1 Federal Land in the West. The federal government owns roughly half of all land in the eleven contiguous western states. Map created by Olivia den Dulk.

Challenges to federal land ownership have a long history in the American West going back to the terms of statehood, from California in 1850 to Alaska in 1959. Historian William Graf describes some of the most significant early rebellions. The first focused on the adequacy of land grant authorities and the need for irrigation, and it ended with the General Revision Act of 1891. The second dealt with forested lands, particularly after presidents in the 1890s and 1900s reserved millions of acres of what we now call national forests in the West, and it ended around the time of the Weeks Act of 1911. The third focused on grazing land and mineral rights, and it calmed considerably after the Taylor Grazing Act of 1934.

The earlier rebellions took place before the federal government developed a comprehensive commitment to environmental protection (e.g., the National Environmental Policy Act of 1969, the Clean Water Act of 1972, the Endangered Species Act of 1973, etc.) and before Congress had defined multiple use management and wilderness preservation (e.g., Multiple Use Sustained Yield Act of 1960, the Wilderness Act of 1964, the Federal Land Policy and Management Act of 1976, the National Forest Management Act of 1976, etc.). Since the landmark environmental legislation of the 1960s and 1970s, there have been three additional periods of conservative rebellion against federal land and resource authority, and the standoff in Nevada and the occupation in Oregon can be understood as their evolutionary product. The first period of rebellion was the . It was waged by westerners, both Democrats and Republicans, with material interests in federal lands who challenged federal authority in response to specific changes in federal land law and federal administration by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM). The Sagebrush Rebellion was waged in the era of print media and nightly news, and it largely involved the tools of state legislation, political organizing, and limited civil disobedience.