Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC 29403

www.historypress.net

Copyright 2014 by Kerry Walters

All rights reserved

Cover: Postcard of the National Hotel, 1907. Courtesy of John DeFerrari.

First published 2014

e-book edition 2014

ISBN 978.1.62585.171.0

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Walters, Kerry S.

Outbreak in Washington, D.C. : the 1857 mystery of the National Hotel disease / Kerry Walters.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

print edition ISBN 978-1-62619-638-4 (paperback)

1. Epidemics--Washington (D.C.)--History--19th century. 2. Curiosities and wonders-Washington (D.C.)--History--19th century. 3. National Hotel (Washington, D.C.)--History--19th century. 4. Buchanan, James, 1791-1868. 5. Public health--Washington (D.C.)--History--19th century. 6. Panic--Washington (D.C.)--History--19th century. 7. Conspiracies--Washington (D.C.)--History--19th century. 8. Washington (D.C.)--History--19th century. 9. Washington (D.C.)--Social conditions--19th century. I. Title. II. Title: Outbreak in Washington, DC.

RA650.5.W35 2014

614.4975309034--dc23

2014033893

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

For Michael Brown, MD

Dedicated physician & enthusiastic history buff

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Many thanks to Kim and Jonah, to Robin Jarrell for her help with the illustrations, to Gettysburg College for the sabbatical that allowed me to write the book, to Hannah Cassillys commissioning it as well as running down a few hard-to-locate images and to Project Editor Katie Stitelys expert guidance. Finally, thanks to Dr. Michael Brown, a physician who always livens up office visits with fascinating conversation about American history. I dedicate this little book to him.

INTRODUCTION

PANIC IN WASHINGTON

It is now believed that not less than seven hundred persons have been seriously and dangerously affected by the National Hotel poison at Washington; and some twenty or thirty deaths have occurred in consequence.

the Pennsylvanian, May 27, 1857

Beginning in early spring and continuing regularly through the summer of 1857, frightening rumors swept through the nations capital and then, thanks to the still-newfangled telegraph, across the entire nation. It seemed that a mysterious malady had erupted in the National Hotel, one of the citys premier lodging establishments, not once but twice. This wouldnt have been especially newsworthy except for the fact that Presidentelect James Buchanan lodged at the hotel on both occasions, and that he and other dignitaries in his entourage were stricken. Buchanan was ill for months afterward, and four of his companionsa nephew, two members of Congress from Buchanans own state of Pennsylvania and a states rights fire-eating ex-governor from Mississippiperished.

The presidential election of 1856, in which Buchanan bested two opponents, had been a particularly nasty one. The nation had been wrangling in an increasingly heated way over the issue of human bondage for years, but things had taken a dangerous turn, in 1854, with the passage of federal legislation that opened the westward territories to the expansion of slavery. The Kansas-Nebraska Act, as it came to be called, galvanized slaverys opponents as no other congressional act had, and within months, they put together a new political coalition whose members christened themselves Republicans. A lanky lawyer from Illinois named Abraham Lincoln soon cast his lot with the coalition and vigorously campaigned for John C. Frmont, the partys first presidential candidate. Buchanan was the nominee of the Democrat Party, whose members generally favored the expansion of slavery into the territories. One of their own, Illinois senator Stephen Douglas, had actually written the Kansas-Nebraska Act. The third candidate in that 1856 race was ex-president Millard Fillmore, who ran on the American Party or Know-Nothing ticket.

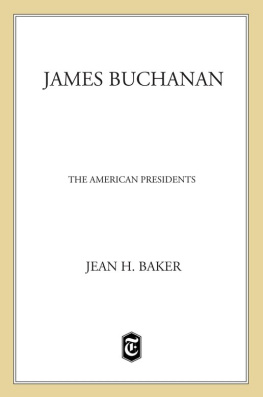

James Buchanan, the drab career politician who became the fifteenth United States president and the most famous victim of the National Hotel disease. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

The campaign rhetoric that election year boiled over with recriminations, accusations and dark insinuations that perfectly matched the angry national frame of mind. After the votes were counted and the winner decided, tempers continued to run hot. So when the news broke that President-elect Buchanan had fallen ill during his stay at the National Hotel, it was easy, given the distrustful post-election climate, for many to wonder if he had been poisoned by political enemies. That possibility alone was enough to strike horror in the hearts of some and glee in the hearts of others. Once introduced, the rumors of foul play persisted for months and, indeed, for years afterward, in some quarters. But as spring turned into summer, the poison theory gave way in most peoples minds to the alternative hypothesis that a frightening disease of unknown origin had hit the National and that it could be lying in wait for the rest of Washingtons citizens. The citys mayor, backed by a handful of medical authorities, did everything he could to scotch the rising panic. But for a few weeks, residents of the capital city, many of whom remembered a terrible cholera outbreak less than a decade earlier, were in a state of panic. Things only got back to normal when it became clear that the malady was limited to the National Hotel and caused, so most of the scientific experts at the time agreed, by noxious vapors or miasma from backed-up sewage.

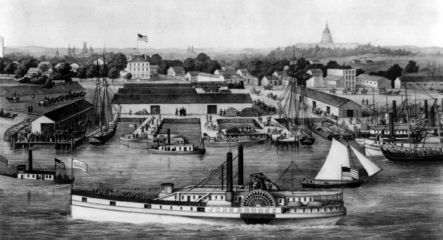

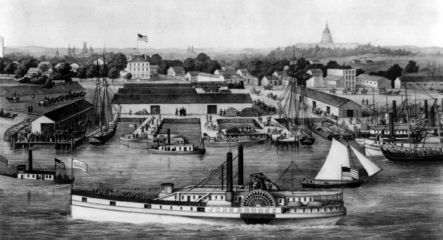

This 1863 lithographic view of Washington from the Sixth Street Wharf is pretty much how the city looked when Buchanan was president. The unfinished Washington Monument is on the left and the Capitol dome, under construction during Buchanans administration, is on the right. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Today, the National Hotel disease, as it came to be known, is all but forgotten. The building is long gone, torn down in 1942, its old site on Pennsylvania Avenue currently home to the Newseum. The outbreak usually gets a passing nod from academic historians of this period of the nations history, but it rarely shows up in popular histories and has never been fully explored by anyone. This is a shame for at least four separate reasons.

In the first place, the public response to the malady is a good case study of how easy it is for panic to spread. Its also yet another example of how eager people are to embrace rumors of conspiracy, often hanging on to suspicions of foul play long after it becomes clear that such suspicions simply arent supported by the facts. Fueled by rumor, innuendo, half-truths, partisanship and incendiary journalism, distress over the origins and scope of the National Hotel disease awakened both panic and cloak-and-dagger excitement that, for a while, terrified and titillated the American public. As such, it belongs to the same lineage as the AIDS scare of the 1980s, when the origin of the disease was still undiscovered and rumors abounded that CIA-employed biologists conspired to manufacture the virus in order to target specific populations.

Next page