Praise for BLACK PEOPLE ARE MY BUSINESS

Lewis intervenes by re-establishing the boundaries and intergenerational building blocks of the Black Arts Movement by situating Bambara as a midwife for the creative legacy of the moment. He also reorients his readers to Bambaras role as foremother to some of the most acclaimed and well-read works by black women. This is essential for recognizing and placing Bambara within a more sustained discourse on the Black Arts Movement and Black womens evolution from that moment into their own creative renaissance. A necessary and overdue study.

Kameelah L. Martin, professor of African American studies and English, College of Charleston

Lewis captures the significance of one of the most important figures in black and womens liberation struggles of the 60s and 70s in the U.S. Though Bambara has been undervalued as a revolutionary writer/activist/theorist of the Black Arts Movement, Lewis articulates in new ways, through an examination of her short stories and novels, the nature of her Black nationalist/feminist commitments and her spiritual wholeness aesthetic. Lewis also underscores how Bambara practices nation building in her art in unapologetic, creative, and brilliant ways.

Beverly Guy-Sheftall is founding director of the Womens Research and Resource Center and Anna Julia Cooper Professor of Womens Studies at Spelman College

Lewis does a superb job of defending a unique and overdue analysis of Toni Cade Bambaras fiction. The technique of viewing Bambaras fiction through the lens of the spiritual wholeness aesthetic with its most frequent source in the Black Aesthetic Movement moves readers attention from the dominant paradigm of viewing Bambaras fiction from a heavily womanist perspective to an interrogation of how Bambaras spiritual, political aesthetic reflects an interweaving of self and ethnic identity, community engagement and responsibility, a balancing of black male and black female identity and of how self-awareness or lack of it influences interactions within and outside the black community.

Joyce A. Joyce, professor of English, Temple University

Black People Are My Business offers an insightful and empathetic analysis of Bambaras complete corpusher popular short stories, her novels, and her nonfiction prose. Thabiti Lewis is an astute reader who illuminates the many ways in which Bambara was and is an indispensable writer.

Cheryl A. Wall, Zora Neale Hurston Professor of English, Rutgers University

There cant be enough good books on Toni Cade Bambara, so Thabiti Lewiss Black People Are My Business is a real gift. His close readings of Bambaras fiction adds an important layer to the conversation about Bambara and, as importantly, about reading/writing as a practice of liberation in African American literary studies.

Dana Williams, professor of African American literature, Howard University

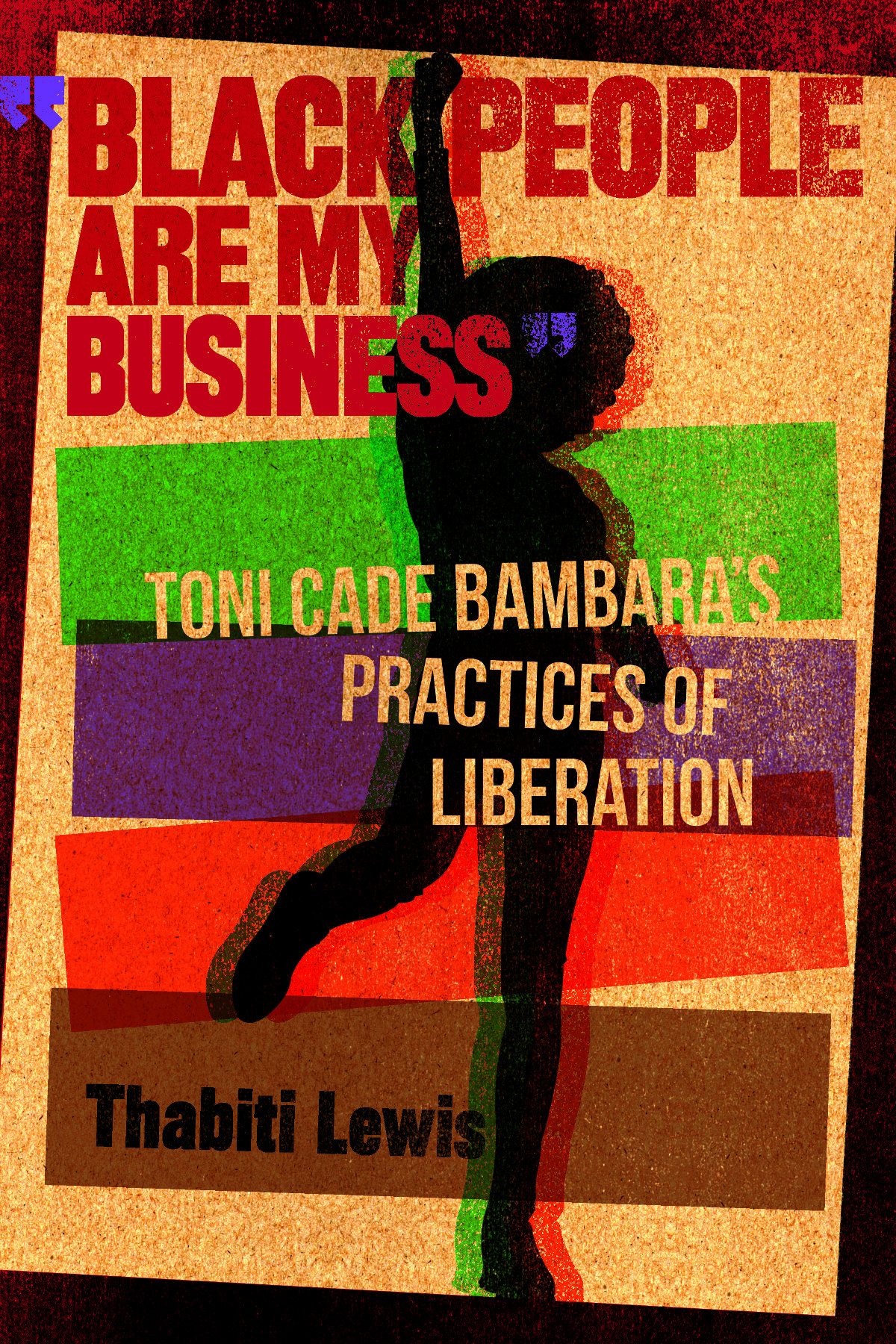

Black People Are My Business

African American Life Series

A complete listing of the books in this series can be found online at wsupress.wayne.edu

Series Editor

Melba Joyce Boyd

Department of Africana Studies, Wayne State University

Black People Are My Business

Toni Cade Bambaras Practices of Liberation

Thabiti Lewis

Wayne State University Press

Detroit

Copyright 2020 by Wayne State University Press, Detroit, Michigan 48201. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced without formal permission.

ISBN 978-0-8143-4429-3 (paperback); ISBN 978-0-8143-4607-5 (case); ISBN 978-0-8143-4431-6 (ebook)

Library of Congress Control Number: 2020935129

Published with support from the Arthur L. Johnson Fund for African American Studies.

Wayne State University Press

Leonard N. Simons Building

4809 Woodward Avenue

Detroit, Michigan 48201-1309

Visit us online at wsupress.wayne.edu

Contents

No book comes to fruition without the help, input, and support of many entities. This book is no different. Black People Are My Business has its genesis in my dissertation work at Saint Louis University under the direction and support of Joyce Uraizee, Don Matthews, and Stephen Casmier. It was an important topic then and remains important. They provided the encouragement and space to explore Bambara and Black culture, feminism, and nationalism in ways that led to the final product here before the reader. I also want to thank the many people who, at different points over the past four or five years, either gave me lodging in their home, challenged my conceptual framework, or helped to tease out ideas with mesome of them did all three things. It is only fitting that a study of Bambara would be published by Wayne State University Press, because she served on one of the early editorial boards of the African American Life Series. It is an honor, and I honor her spirit and intellectual legacy with this book.

Earlier I mentioned that many people provided support in multiple ways. Over the years I have traveled to Atlanta, where my brother, Lawrence Jackson, often opened his home to me when I visited the Spelman and Emory archives to work on the book. During those trips Larry often modeled for me discipline and commitment. Each morning, during a visit, he would cut short any conversation by 9 a.m. and tell me to have a productive workday, and at the end of the day we would meet back at his house to run and go to dinner. I am also grateful to my good friend Dana Williams who ventured out to the Pacific Northwest to discuss the project and also made space for me at her home and linked me up with Eleanor Traylor, who blessed me with insights into Bambara, her own genius, no-nonsense perspectives, and even gave me lodging.

My good friend and mentor Donald Matthews never left my side. Although we long ago finished the dissertation, he took me to the Las Vegas desert to reconstruct a couple of key chapters for the book and, for that, I am forever grateful. I am equally appreciative of John and Maria Jackson who offered the quiet of their home at one point. I would be remiss if I did not acknowledge my cousin who suggested the idea of writing about Bambara as a dissertation topic and Marie-Paule, Carolyn, and Stephanie who helped juggle childcare in the early days of parenting so I could write.

In addition, I am appreciative of the extensive intellectual community that helped shape this text, allowing me to share ideas at key moments. Among those who aided me in finding the right words to describe what it is I think Bambara is doing are people such as Dana and Don, Jerry Ward Jr., Davarian Baldwin (my brother from another and king of frameworks), Kalamu Ya Salaam, Linda Holmes, Kameelah Martin (African spirituality guru), Scot Brown, Pavithra Narayanan (who encouraged me to speed things up), Lisa Alexander, Beauty Bragg, Joyce Ann Joyce, Bakari Kitwana (thirty-three years and counting), Haki Madhubuti, Eugene Redmond, and Tony Bolden (who, without knowing it, pushed me in the right direction and gave me the idea for one of my chapters). I think Bambara would love the village that has supported the journey of this book, because she was known to open her home to folk or lodge with folk to work on projects.

I also want to thank other supporters such as the Washington State University ADVANCE Grant, the Timeul Black Fellowship, Black Metropolis Fellowship, the Washington State University English Department Buchanan Summer Grant, and the Emory University Marble library short-term fellowship. A very special thanks to Melba Boyd for her immense support of this project and for convincing me to bring the book to the African American Life Series. I want to thank Sandra Judd for her editorial assistance and also Annie Martin. Finally, I want to thank my biggest supporters: my daughters Safina Theard-Lewis and Ayodele Theard-Lewis and my wonderful wife, Angele Theard, all of whom have endured my fluctuating mood and uselessness at different points during the writing process.

Next page