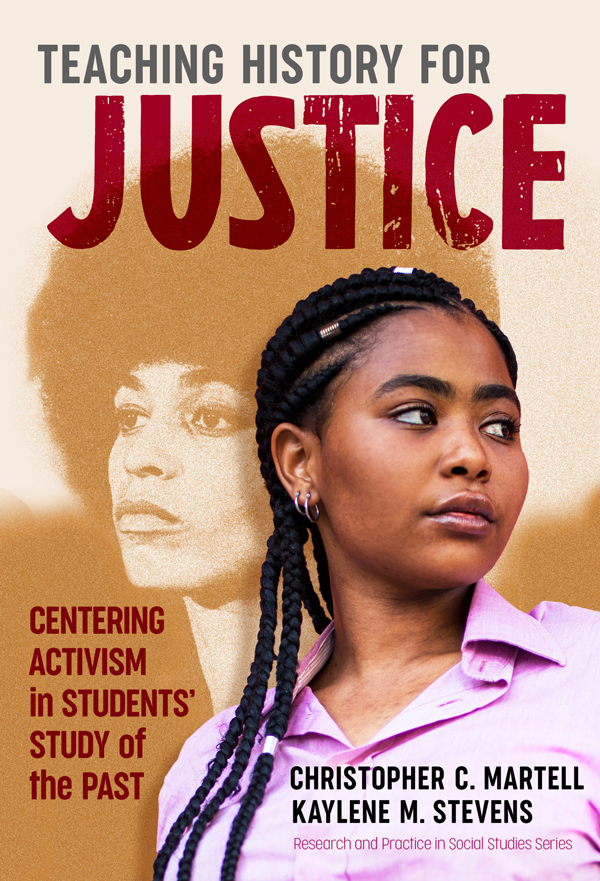

Christopher C. Martell

Kaylene M. Stevens

Front cover images: Student by MStudioImages / iStock by Getty Images; Angela Davis courtesy of the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the publisher. For reprint permission and other subsidiary rights requests, please contact Teachers College Press, Rights Dept.:

We dedicate this book to all the students we have taught and all the educators we have worked with. May they work for justice and be activists for change.

CHAPTER 1

Centering Justice in Students Study of the Past

Oppression is interwoven into our histories. In the United States and globally, race, gender, class, sexual orientation, religion, and other social identities have long been used to create systems of advantage and to help certain groups maintain their power. In recent decades, this has been made more complex by the rise of populist nationalism and counterreactions to movements that seek equity for oppressed groups. In the United States alone, numerous recent historical events have highlighted persistent (and, in many cases, growing) social inequity: the Los Angeles Riots; the murder of Matthew Shepard and many other hate crimes targeting lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) people; the treatment of Muslim Americans after September 11; the lack of care for Black and low-income people during and after Hurricane Katrina; the killing of numerous unarmed Black and Brown people, including Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown, Sandra Bland, Breonna Taylor, and George Floyd; the recent media exposure of the persistent gender discrimination and sexual abuse that women have faced in their workplaces and elsewhere; and the executive branchs targeting of Latinx immigrants and poor treatment of migrant families at the Mexican border. In response, several justice movements continue to organize and push for equity, including Occupy Wall Street, Black Lives Matter, and the Womens March.

Yet social systems have been designed on foundations of racism, sexism, classism, and other forms of supremacy, which make them almost invisible to those people with privilege. Despite the fact that recent illuminating events and powerful movements have captured the publics attention, most Americans who are in positions of power willingly or unwillingly choose to ignore our current social divisions. For instance, only 37% of White Americans feel that the country must go further in providing equal rights for people of color (Horowitz et al., 2019), only 42% of American men feel that more progress is needed in gender equality (Horowitz et al., 2017), and only 37% of middle-and upper-class Americans believe that advantages in life are the main factor in personal wealth (Dunn, 2018). Not surprisingly, in those same polls, the majorities of people of color, women, and people with lower incomes respond oppositely. Racism, sexism, classism, and other forms of oppression are maintained by the complicit, and often silent, benefiters of the system.

With this in mind, understanding the concept of inequity, how it functioned in the past (and has led to the present), and how movements of people have organized to create a more equitable society should be a main purpose of not only history education, but also education more broadly. Ultimately, education must be for liberation (Freire, 1970/2000; Lakey, 2004). We can rebuild our history classrooms to help students understand how citizens have formed movements to improve our society. We must give them the tools to understand how activists have done their work across history. In this book, we argue that classrooms should focus on teaching history for justice. In this chapter, we make the case for why it is needed, where it comes from, and what it looks like in practice.

WHY DO WE NEED TO TEACH HISTORY FOR JUSTICE?

A Need for Justice in Education

To prepare citizens to work against these persistent inequities built into every aspect of our society at the local, national, and global levels, our education system needs to center on justice. Schools, and especially history classrooms, should be places where students consider events, eras, and issues related to justice. While there are many different conceptions of social justice education, we work from a definition supplied by Ayers and colleagues (2009) that rests on three pillars:

- Equity: The principle of fairness, which demands that what the most privileged are able to provide to their children (and receive for themselves) must be the standard for all, and that there must be a redressing and repairing of historical and embedded injustices.

- Activism: The principle of agency, which involves a full participation, preparing students to see, understand, and, when necessary, change all before them.

- Social Literacy: The principle of relevance, which involves resisting the effects of materialism and consumerism, as well as resisting the power of social evils rooted in forms of supremacy (i.e., White supremacy, patriarchy, homophobia), and nourishing our awareness of our own identities and our connections with others, and how our lives are negotiated within preestablished power relationships.

Ayers and colleagues argued that social justice education ultimately embraces the three Rs of relevant, rigorous, and revolutionary. It involves a curriculum connected to the lives and cultures of the students. It involves setting high academic standards for all students with embedded support and care to help them reach those standards. It involves a positive transformation of students lives and their communities, but also a rethinking of the larger social order.

Ladson-Billings (2015) recently argued that we must replace the term social justice with just justice to describe our collective work in making the world fairer. She argues that the difference is not only a semantic one, but also a fundamental rethinking of our task as human beings. The term social justice is not expansive enough to help us confront the injustice that permeates all aspects of our society. Ladson-Billings built her reasoning on four main contentions: (1) Social justice has become oversimplified into a buzzword; it may be used due to its fashionableness and without a deeper understanding of inequity and how it works (and how it can be undone). (2) Social justice has become part of a discourse of cant or a deficit view of students, especially students of color or poor students. (3) Social justice has become a political target, especially for those on the far right, labeling it purely as ideological and lacking any substance. (4) Social justice is too narrow, and we lose sight of the big picture and the injustice that prevails across the country and around the world. For these reasons, we also choose to be more intentional in our language, and throughout this book we use the word justice, just justice, to describe what we hope students and teachers will focus on in their work.