Acknowledgments

When I began work on this book in 1995, I expected to complete it in about a year. I had no idea that it would turn into one of the biggest challenges of my life and, in the end, take over five years to complete, with constant rethinking and revisions. The issues examined in the book are among the most knotty and perplexing in modern Japanese history and many of them had never been covered systematically It took an enormous amount of research and conceptualization to bring the story into focus, and I could never have done it without the help of my friends and colleagues.

It began with Merit Janow, with whom I first had the idea for the book, and who gave me constant support and advice.

My greatest thanks are reserved for Bodhi Fishman, whom I have credited chiefly with having researched the book but whose contribution was far greater than that. For five years, Bodhi hunted down thousands of clippings, books, interviews, and articles, reflecting the ever-shifting focus of my writing. In addition, he went over the manuscript countless times and sat with me over the years as we talked over and rethought difficult issues. Bodhi was my true collaborator, and I could not have written the book without him.

In addition, I would like to thank my friends and colleagues in Japan, with whom I have spent many hours discussing these subjects and who urged me to keep writing despite the difficulty of the work. The flower master Kawase Toshiro's and the Kabuki actor Bando Tamasaburo's views on traditional culture were guiding lights to me. Architects Shakuta Yoshiki and Kathryn Findlay filled in my knowledge of architecture, zoning, and city planning. The banker Matsuda Masashi gave me information about the banking crisis.

Karel van Wolferen was a fountain of ideas and advice about Japan's economy and its political dimension; R. Taggart Murphy offered me insights into the financial system; Gavan McCormack was a mother lode of information on the construction state. Donald Richie heard my analyses of Japan's cultural trauma and offered pithy comments concerning cinema. Mason Florence, guidebook author and my partner in a project to revitalize the remote Iya Valley in Shikoku, was a sounding board for issues about rural life and tourism. Gary DeCoker provided academic resources concerning the Japanese educational system. The painter Allan West shared his experiences as an artist and a cultural adviser. The garden designer Marc Keane counseled me on the ups and downs of Kyoto's preservation movement. David Boggett read the manuscript and made suggestions concerning education. Chris Shannon taught me about the Internet in Japan. The writer Brian Mertens brought a journalist's eye to the process, and was one of my most loyal listeners as well as a source of information on many subjects. The Malaysian artist and cultural manager Zul-kifli Mohamad helped me to think about Japan's issues from a wider, Asian point of view.

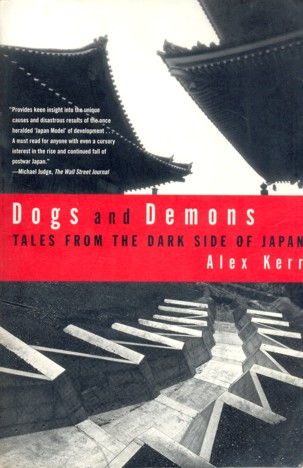

Some of my advisers did not live to see the completion of the book: the essayist and art critic Shirasu Masako told me the story of Dogs and Demons from which the book takes its titie; the writer and philosopher Shiba Ryotaro showed me how far modern Japan had wandered from its own ideals; William Gilkey, a longtime resident of Japan and China, was the source of many anecdotes of old times; the psychiatrist Miyamoto Masao brought conceptual power and humor to the subject of the Japanese bureaucracy; and Andy Kerr, my father, advised me concerning the book's overall tone.

With respect to the Japanese translation of the book, Kazue Chida, friend and former secretary, did the early work; Kihara Etsuko later translated the manuscript in its entirety. I used Kihara Etsuko's work as the basis for writing my own version in Japanese, which was corrected by Nishino Yoshitaka. Throughout this process-resulting in years of delay-my publishers at Kodansha showed unending patience and support.

Julian Bach, my agent in New York, guided the book from its inception; Alice Quinn at The New Yorker introduced me to Elisabeth Sifton at Hill and Wang, who became my stern but brilliant editor. The book benefited tremendously from her wisdom and professional rigor.

Many others offered advice and help while I was at work on this project: Dui Seid in New York, at whose apartment great stretches of the book were written; my secretary, Tanachanan Saa Petchsombat; and my partner Khajorn Khamkong.

As for typing the manuscript, I did that myself. The rest I owe to Bodhi, to my friends and advisers-and to the hundreds of Japanese whom I have never met but who have written or spoken publicly about these issues during the past few years and whose work I consulted. This book belongs to them.

Author s Note

All Japanese names are shown Japanese style: last name first.

The yen/dollar rate has fluctuated widely over the past decade, but for purposes of rough estimation, the rate is about 105 to $1 at the time of writing.

As of January 8, 2001, many ministries and agencies of the Japanese government are being merged and retitled. The names I give are those in use at the time of writing.

Prologue

What I am about to communicate to you is the most astonishing thing, the most surprising, the most marvellous, the most miraculous, most triumphant, most baffling, most unheard of, most singular, most extraordinary, most unbelievable, most unforeseen, biggest, tiniest, rarest, commonest, the most talked about, and the most secret up to this day.

Mme de Sevigne (1670)

The idea for this book came one day in Bangkok in 1996, as I sat on the terrace of the Oriental Hotel having coffee with my old friend Merit Janow. It was a colorful scene: teak rice boats plied the great river, along with every other type of craft from pleasure yachts to coal barges. At the next table, a group of German businessmen were discussing a new satellite system for Asia, next to them was a man reading an Italian paper, and across the way a group of young Thais and Americans were planning a trip to Vietnam. Merit and I had grown up together in Tokyo and Yokohama, and it struck us that the scene we were witnessing had no counterpart in the Japan we know today: very few foreigners visit, and even fewer live there; of those, only a handful are planning new businesses their effect on Japan is close to zero. It is hard to find a newspaper in English in many hotels, much less one in Italian.

The river, too, presented a sharp contrast to the drab sameness of Japanese cities, where we could think of no waterways with such vibrant life along their shores, but instead only visions of endless concrete embankments. Japan suddenly seemed very far away from the modern world-and the title for a book came to me: Irrelevant Japan. Japan kept the world out for so long, and so successfully, that in the end the world passed her by.

However, as I researched this book, it became clear that Japan's problems are much more severe than even I had guessed. Far from being irrelevant, Japan's troubles have serious relevance for both developing countries and advanced economies, for the simple reason that Japan fell into the pitfalls of both. So the title changed.

The key question is: Why should Japan have fallen into any pitfall, when the nation had everything? It reveled in one of the world's most beautiful natural environments, with lush mountains and clear-running streams pouring over emerald rocks; it preserved one of the richest cultural heritages on earth, receiving artistic treasure from all across East Asia, which the Japanese have refined over the centuries; it boasted one of the world's best educational systems and was famed for its high technology; its industrial expansion after World War II drew admiration everywhere, and the profits accumulated in the process made it perhaps the wealthiest nation in the world.