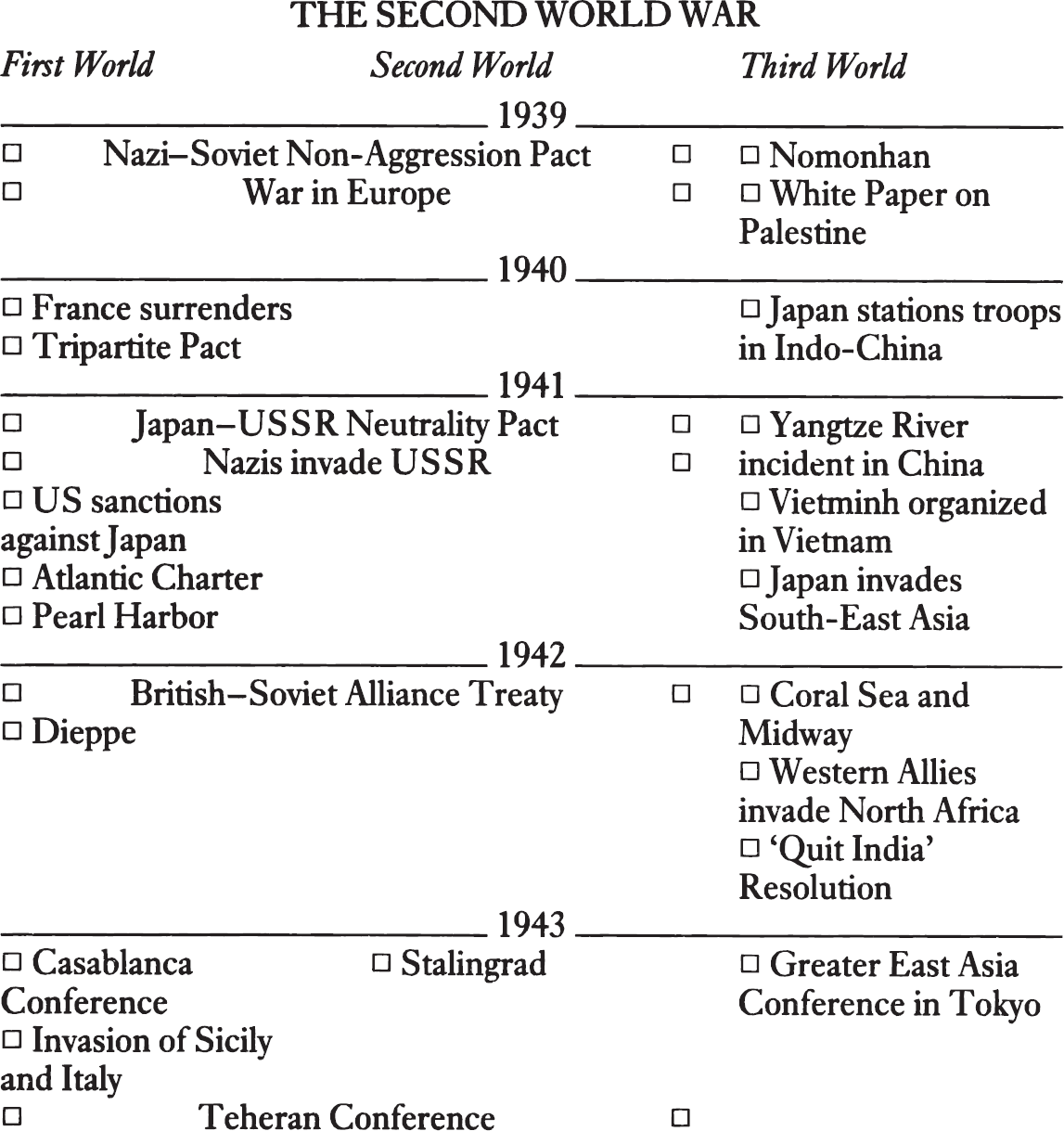

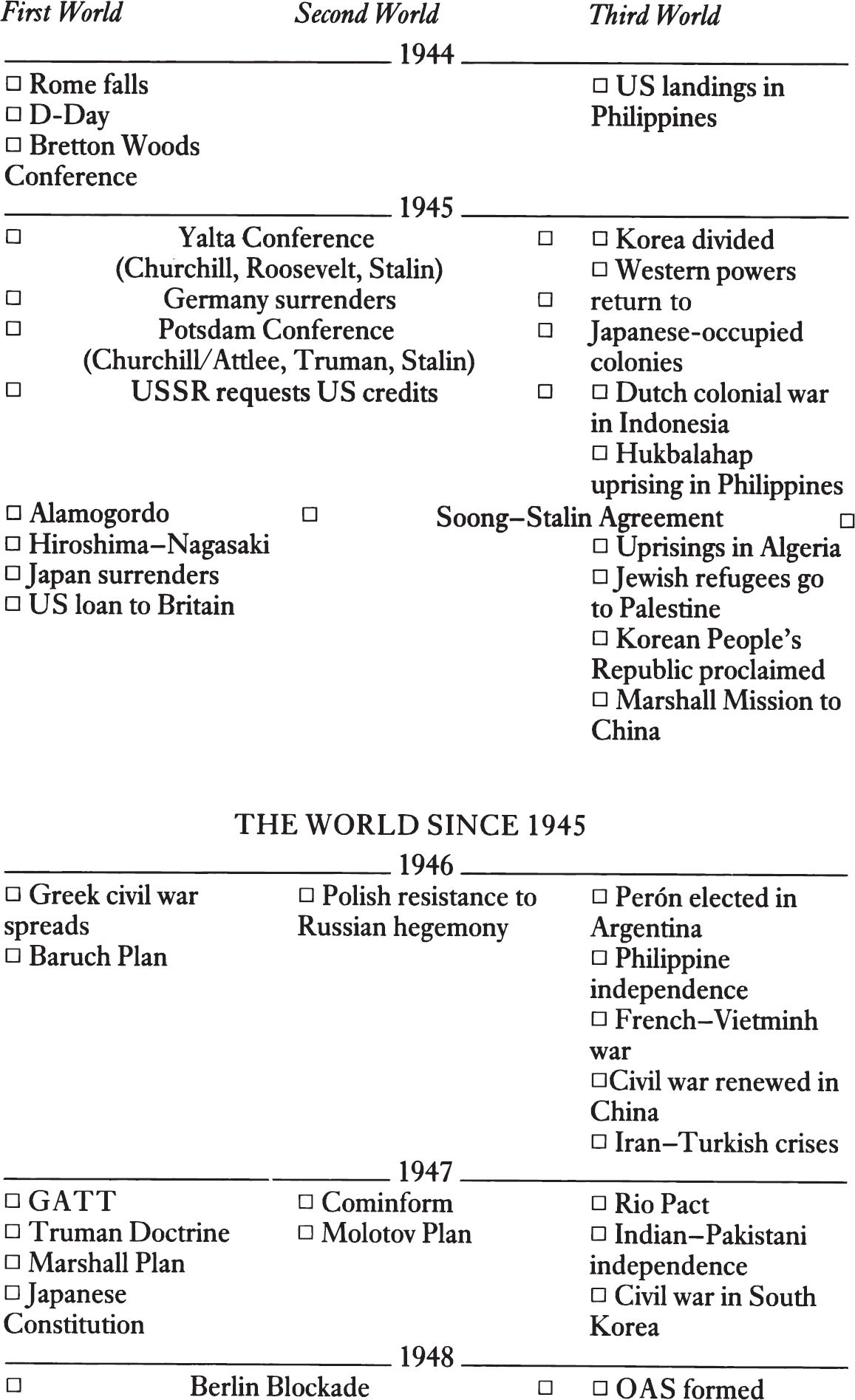

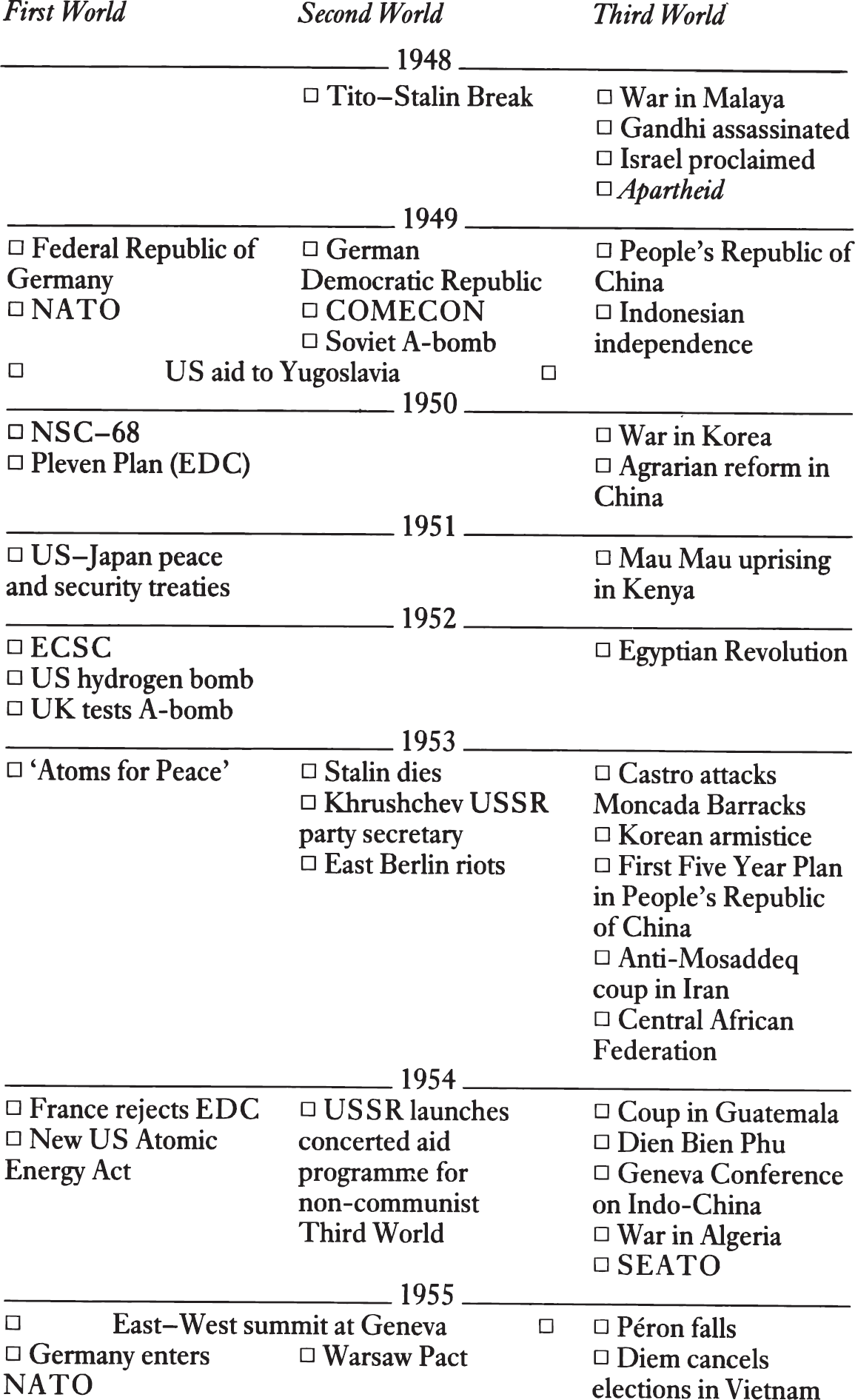

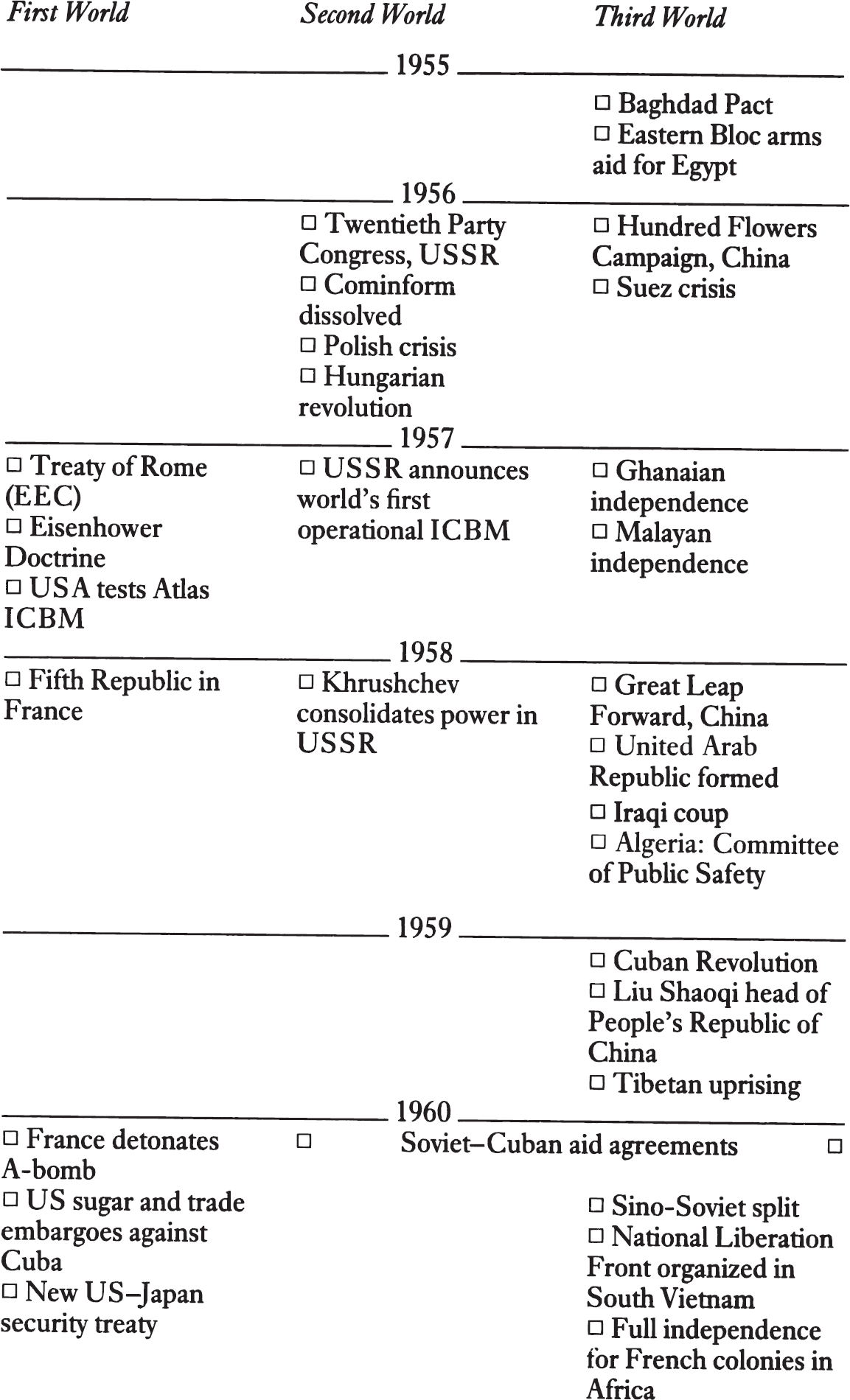

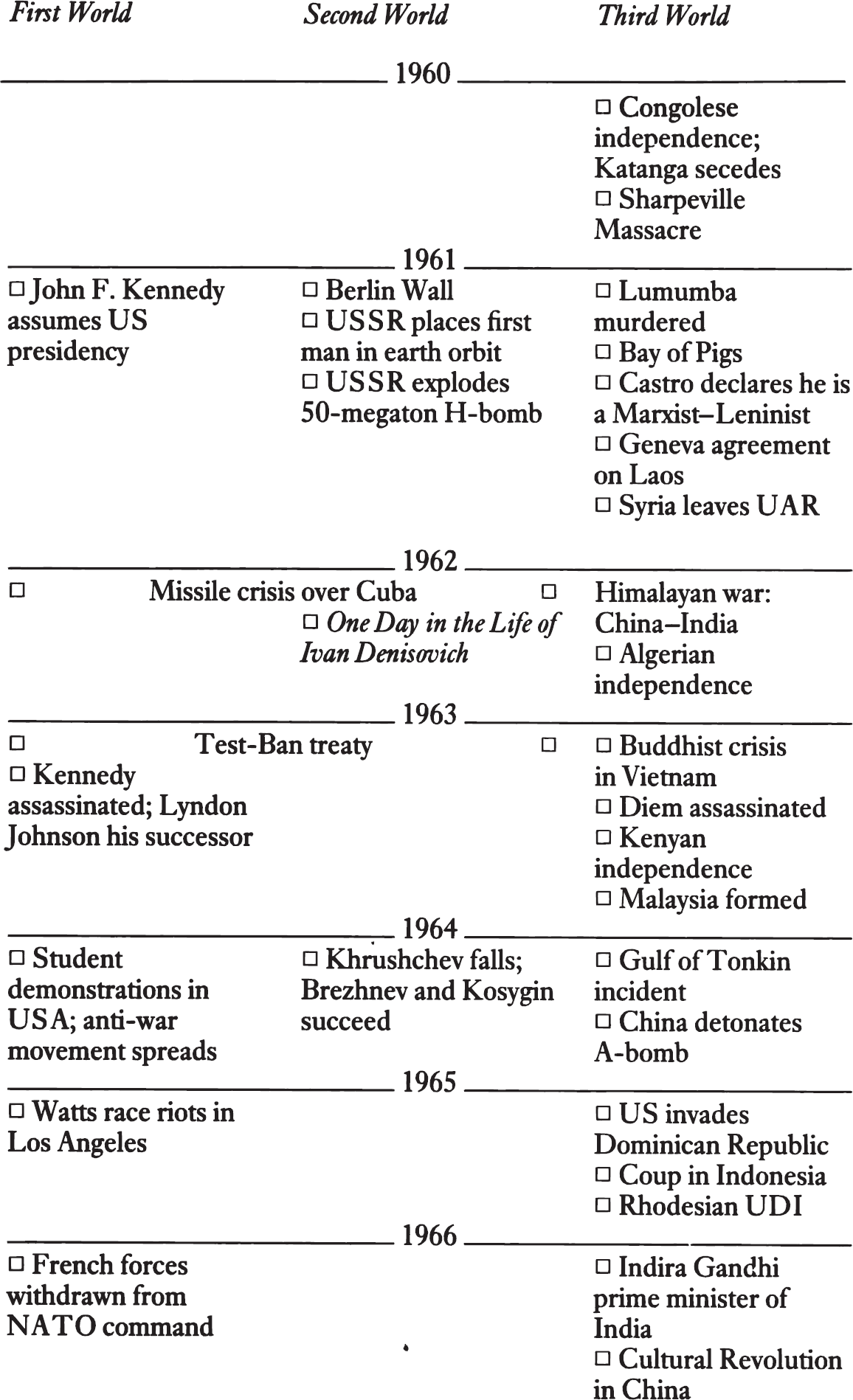

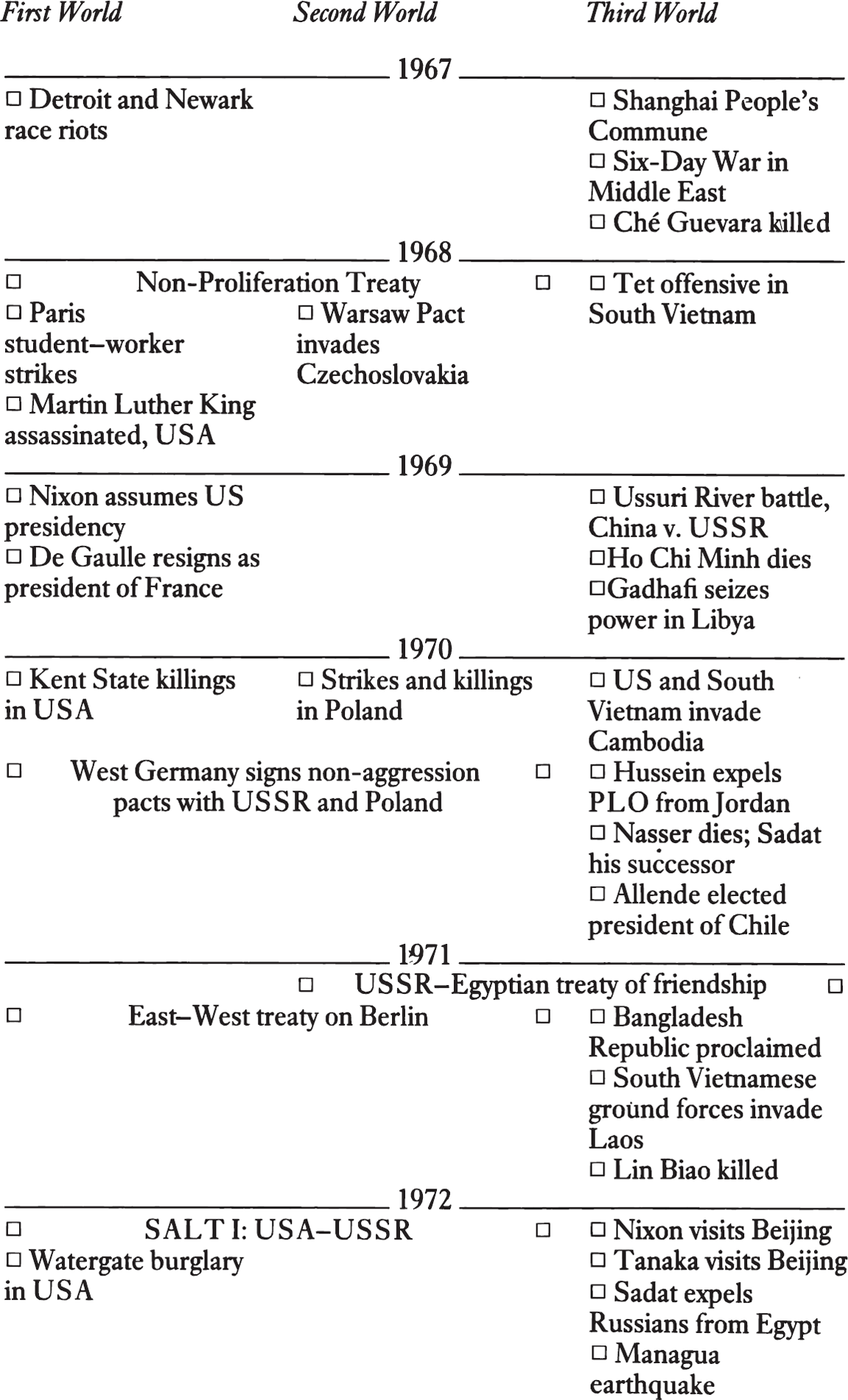

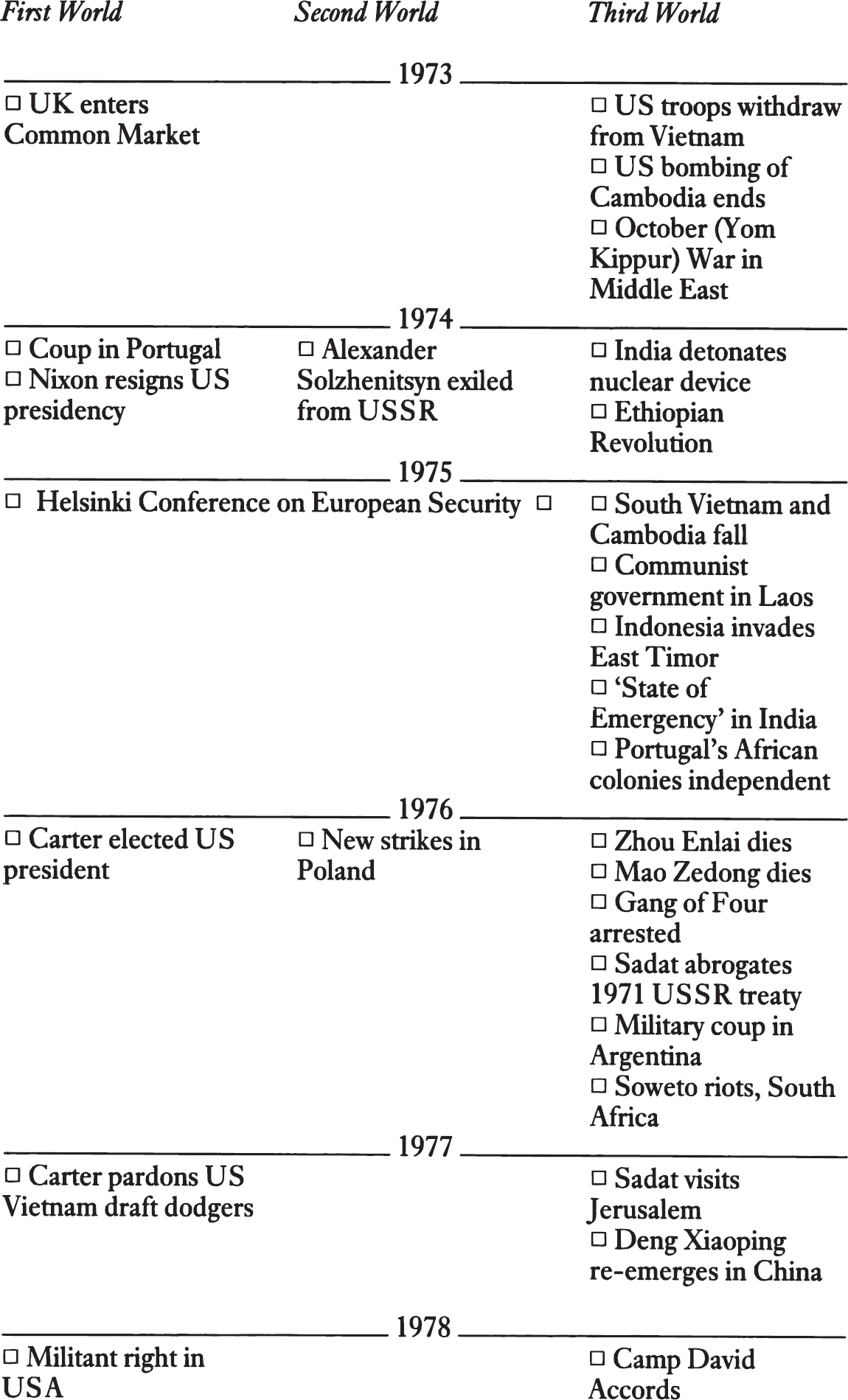

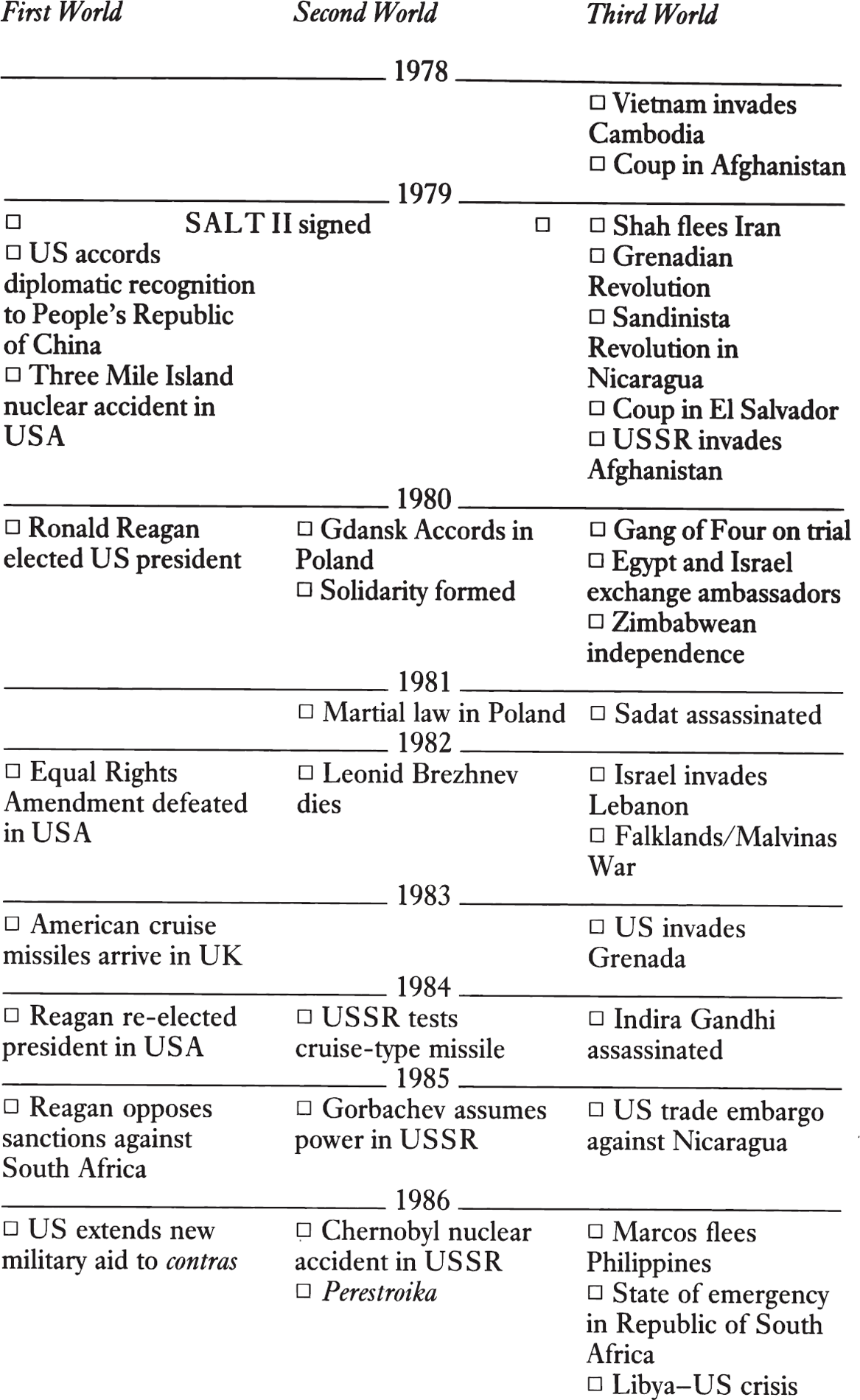

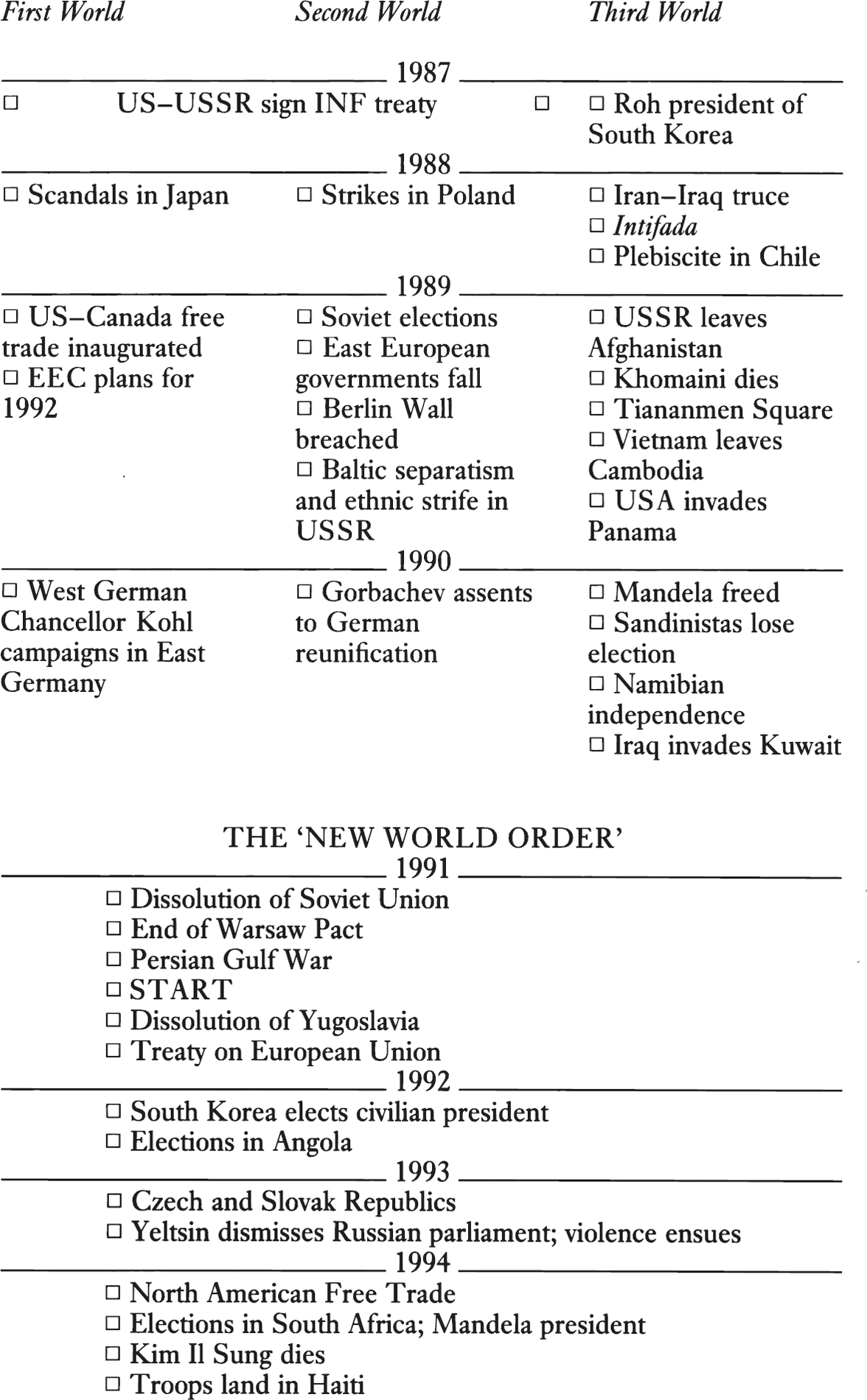

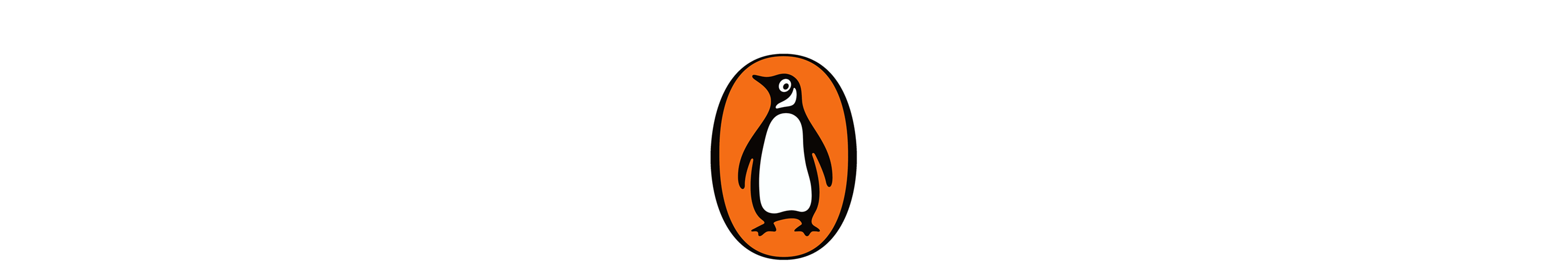

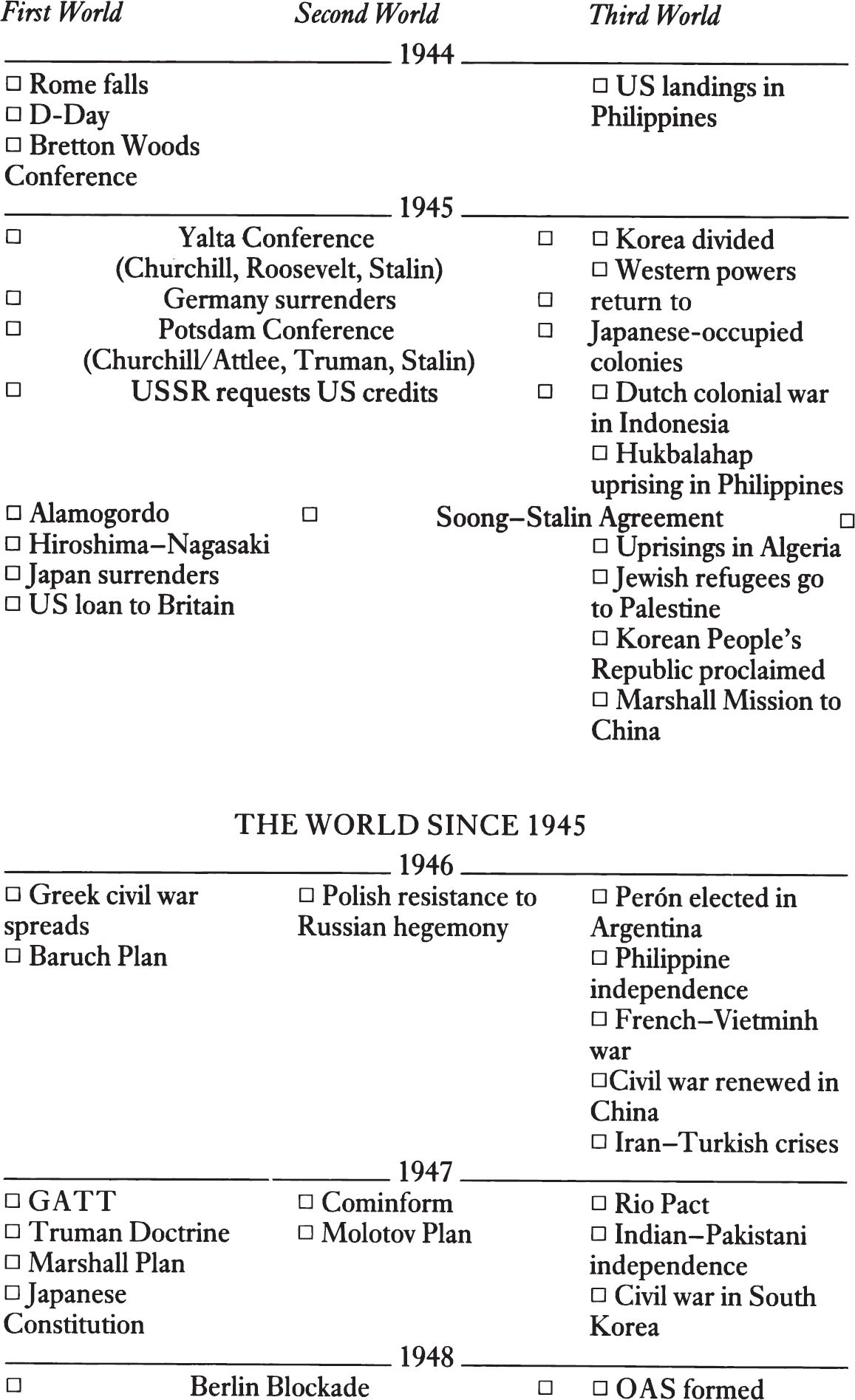

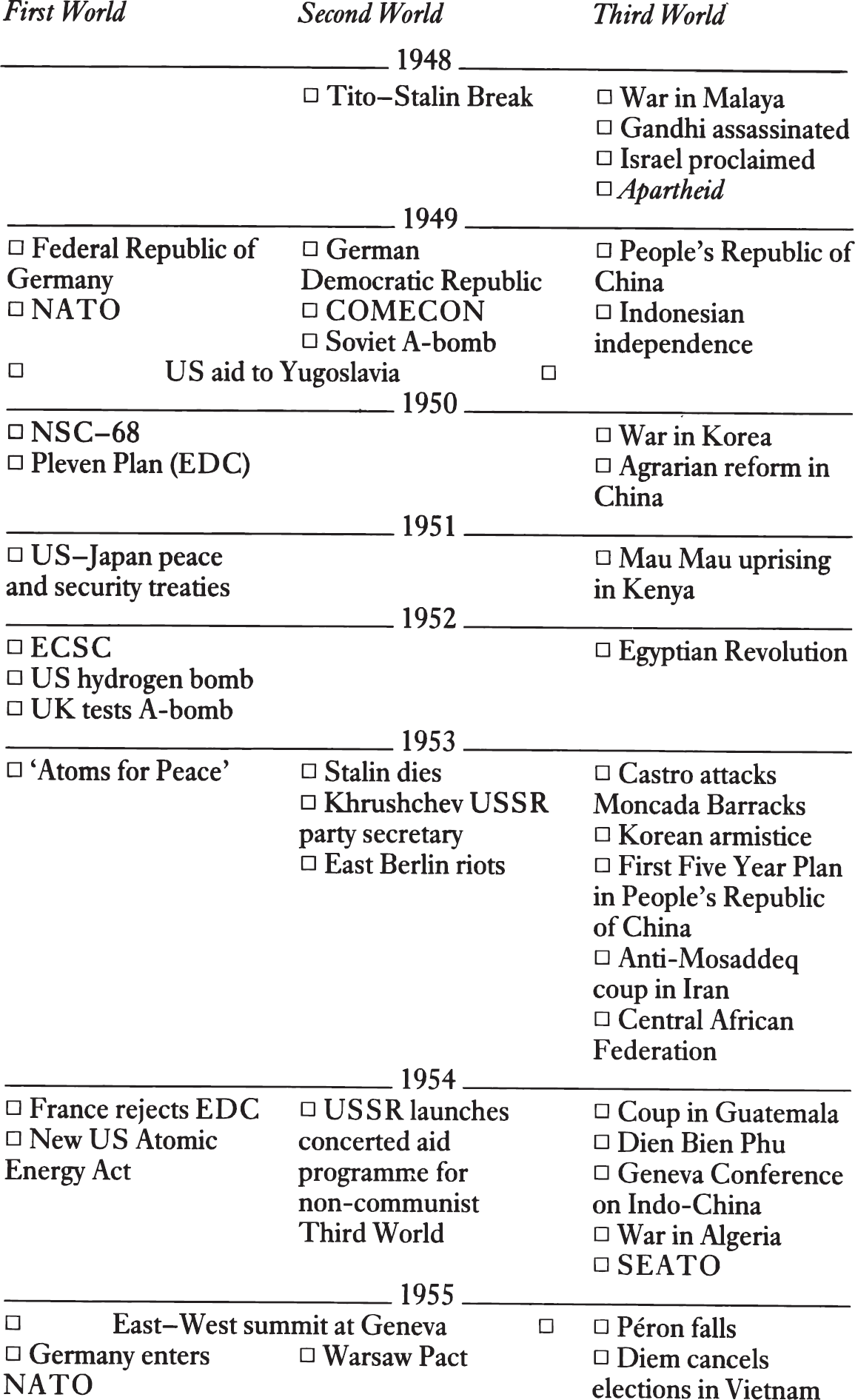

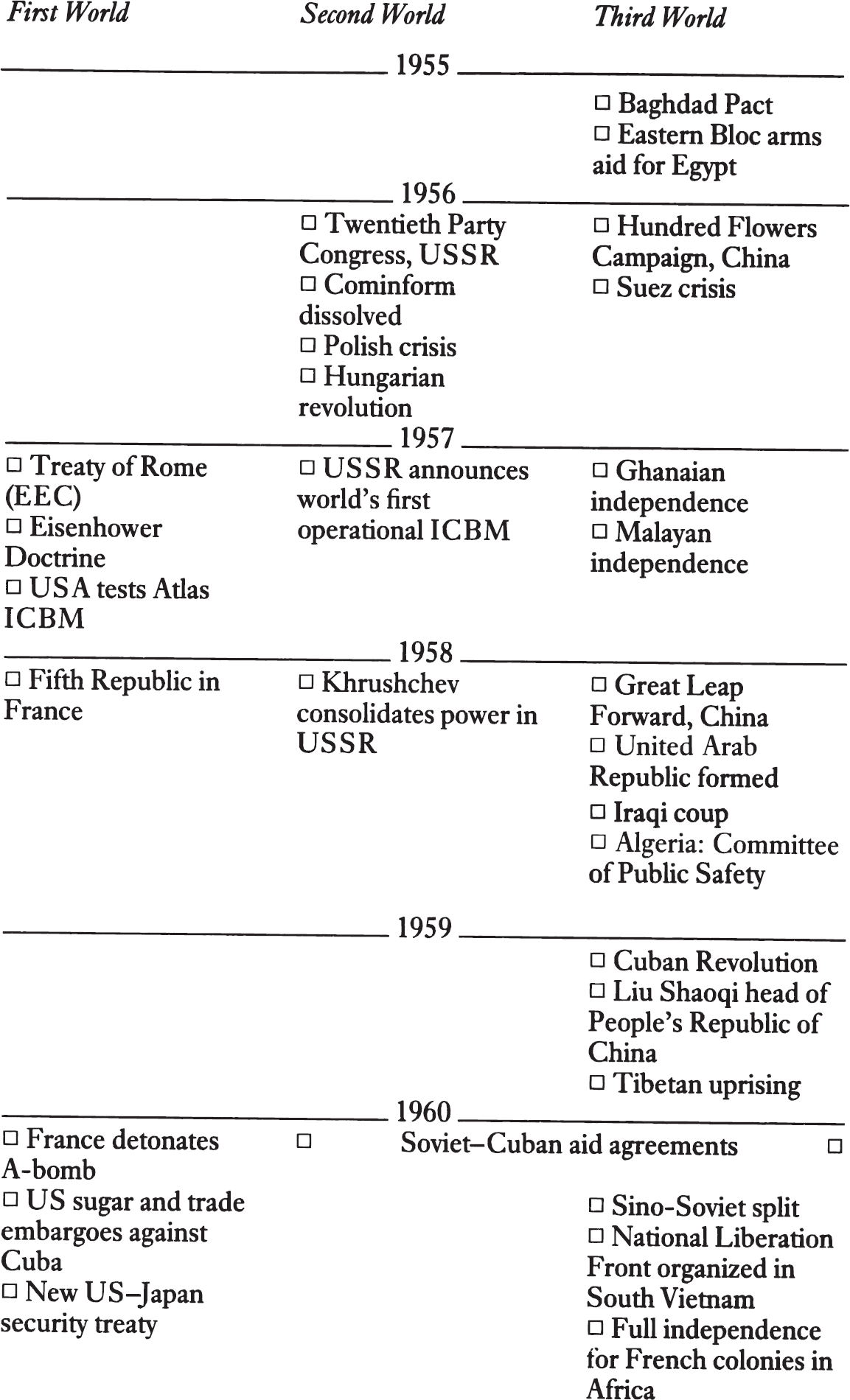

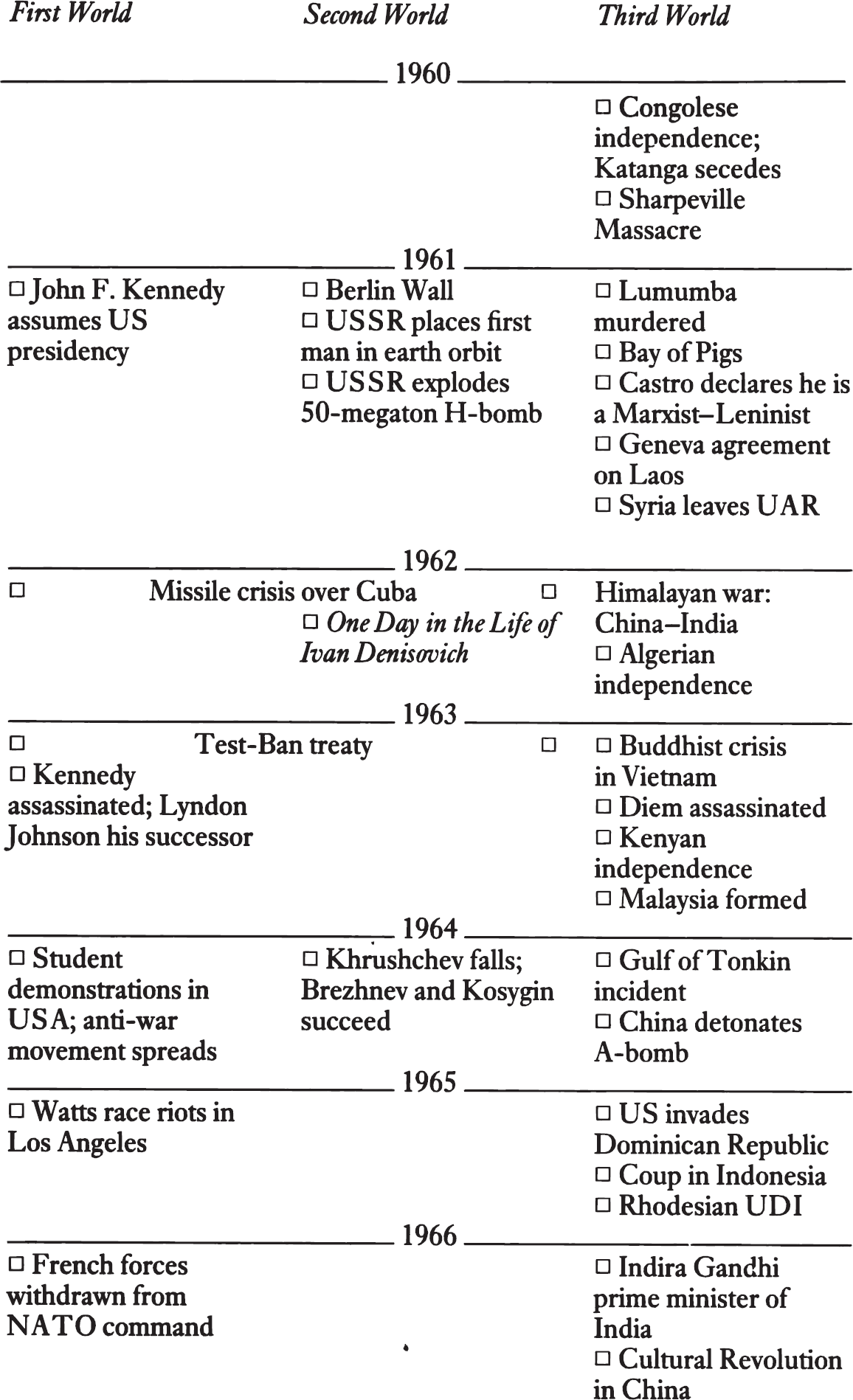

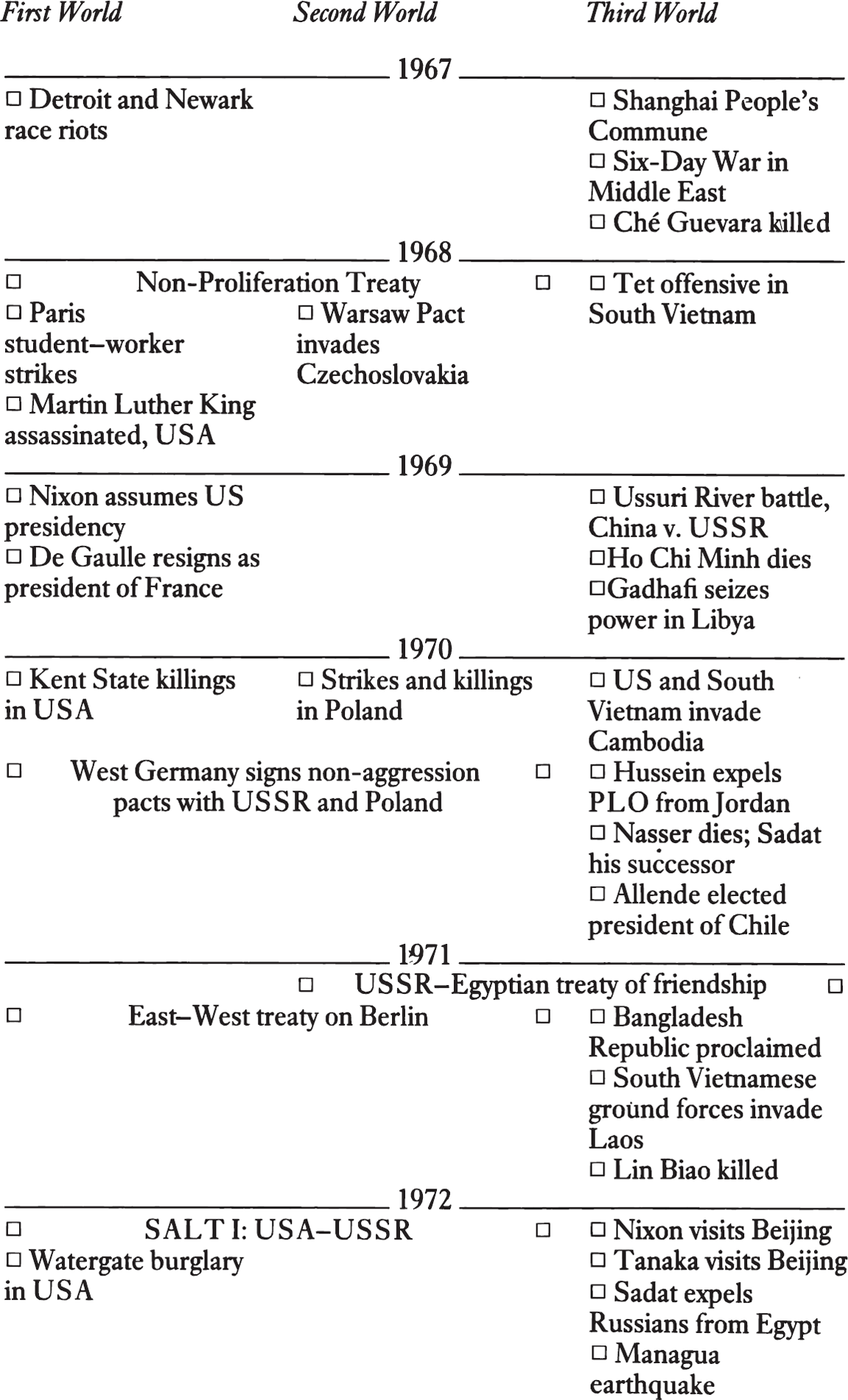

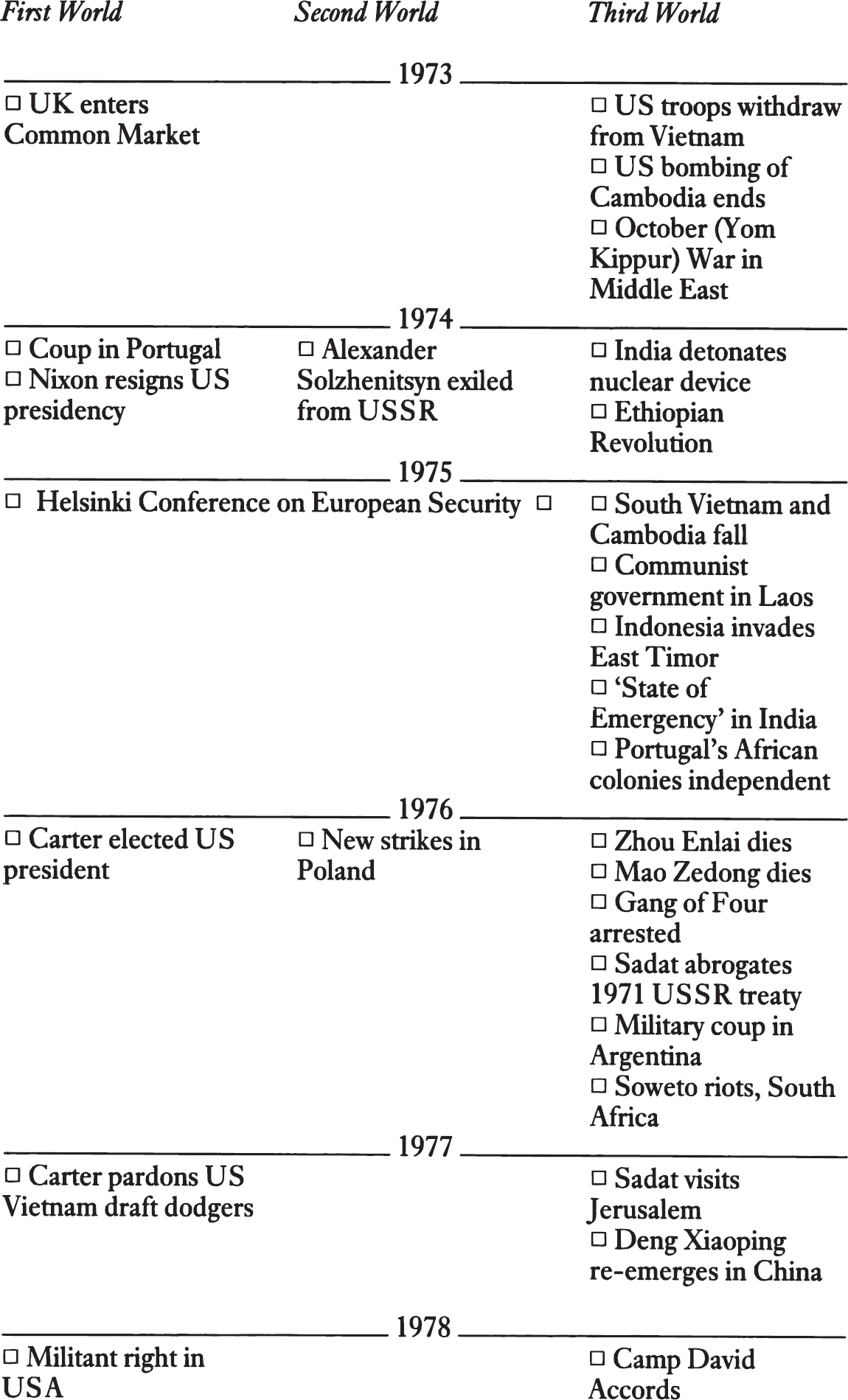

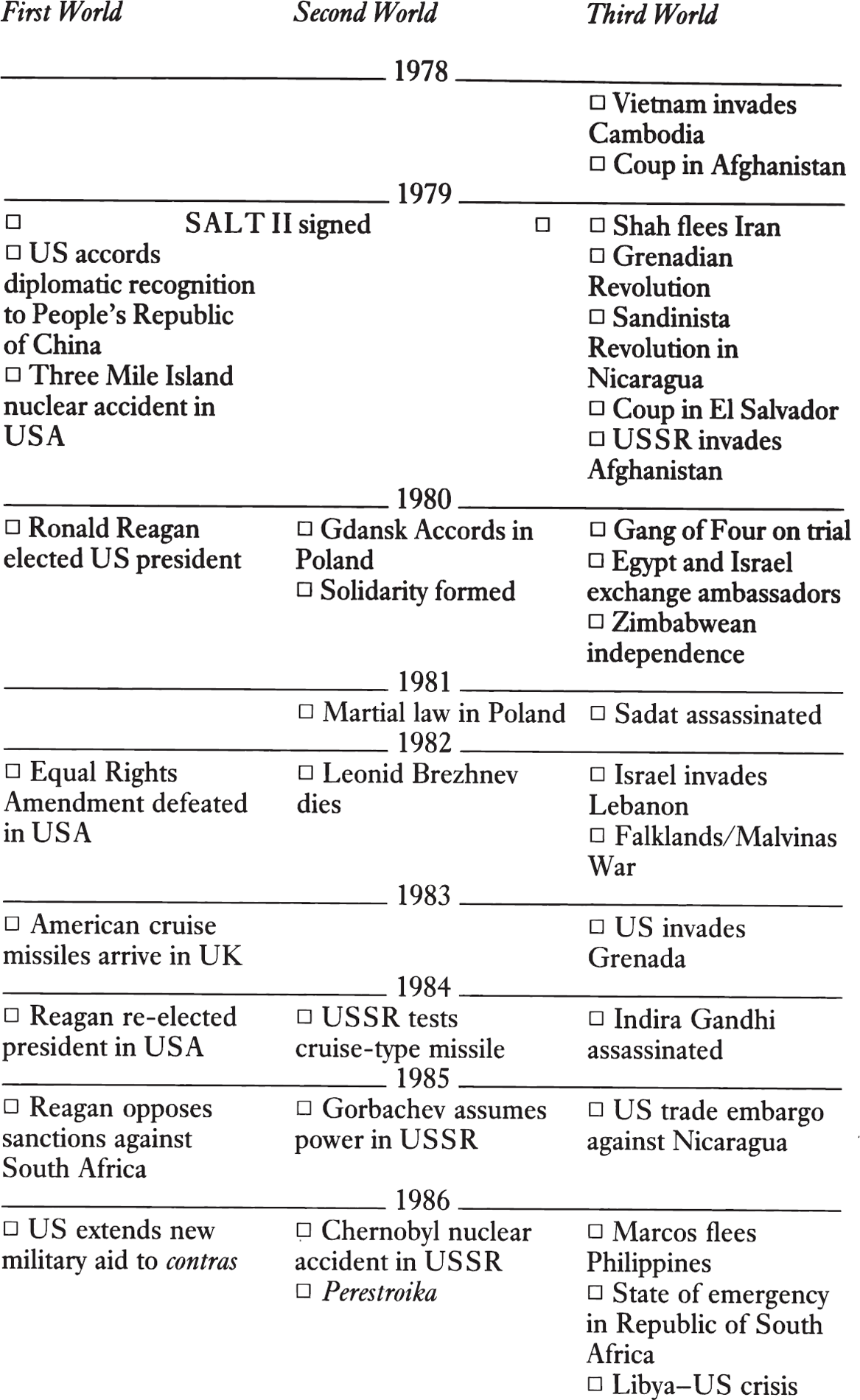

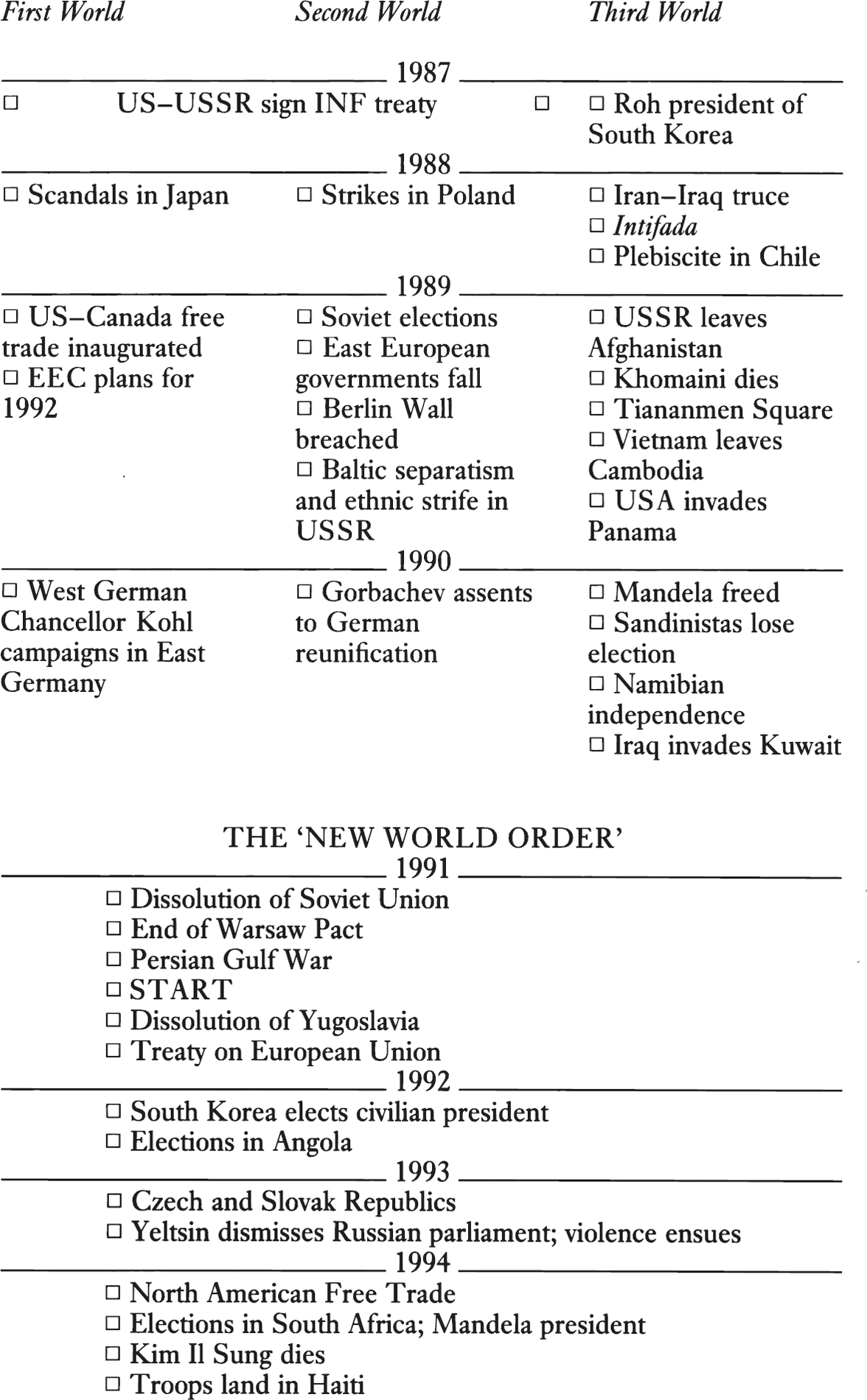

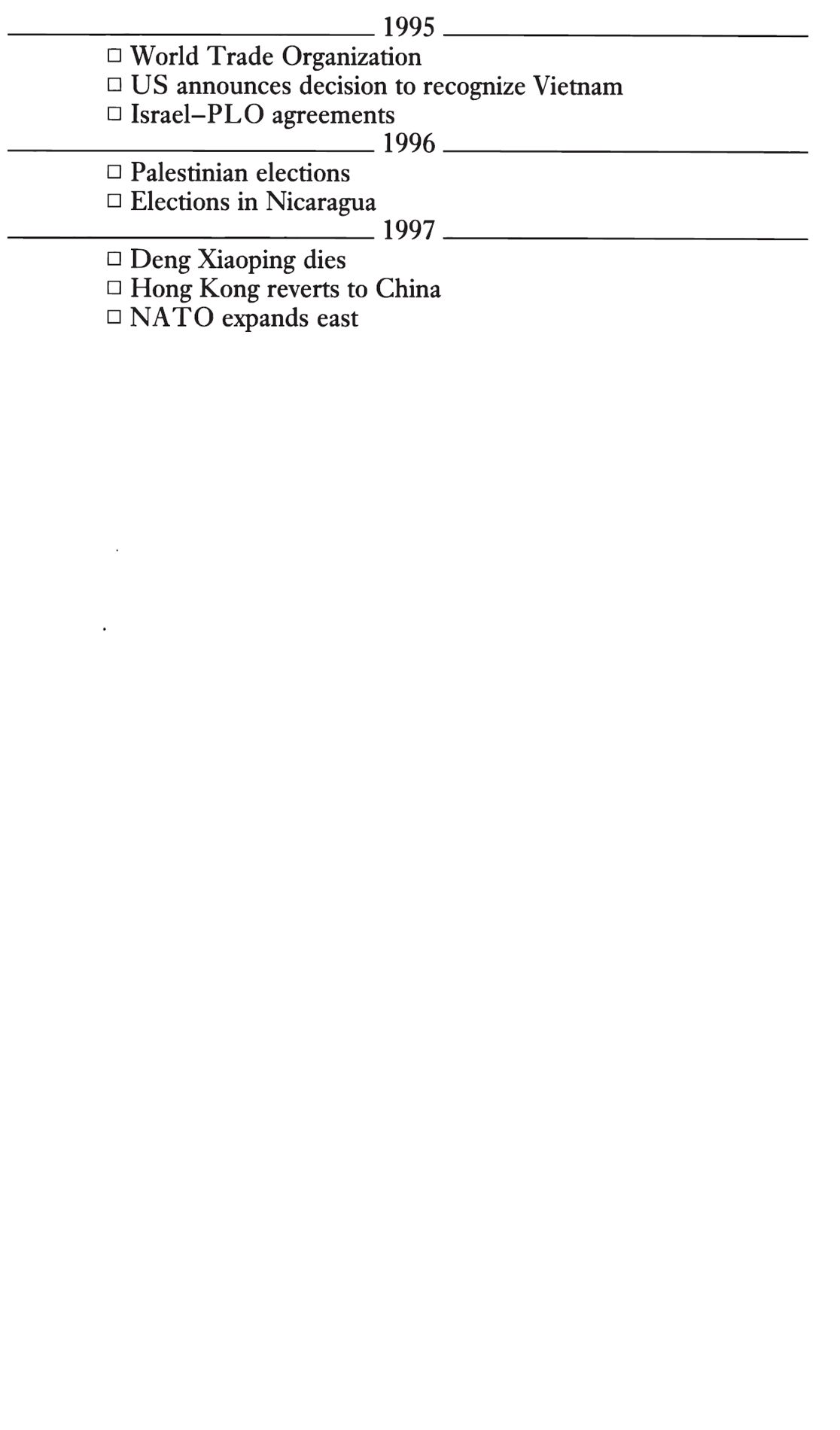

Chronological Table

See the definitions of First, Second and Third Worlds in .

About the Author

T. E. Vadney was born in 1939 and is Professor of History at the University of Manitoba in Canada. He received his BA (Hons.) in Modern History from the University of Toronto and his MA and Ph.D. in United States History from the University of Wisconsin at Madison, where he was a Woodrow Wilson Fellow. His publications include a biography of the American labour lawyer and New Deal politician Donald Richberg, The Wayward Liberal, as well as essays on diverse subjects. At Manitoba he organized the programme in contemporary world history, and he continues to teach and write on US and global affairs.

T. E. Vadney

THE WORLD SINCE 1945

Third Edition

PENGUIN BOOKS

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia

New Zealand | India | South Africa

Penguin Books is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

First published in Pelican Books 1987

Reprinted in Penguin Books 1990

Second edition 1992

Third edition 1998

Copyright T. E. Vadney, 1987, 1992, 1998

ISBN: 978-0-141-93779-3

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorized distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

Preface

This book is a survey of recent global history, although it makes no claim to cover literally everything that has ever happened since the Second World War. To try and do so within the confines of a single volume would result in a mere list of names and dates, and leave little room for explanation. Accordingly the strategy has been to select particular cases as examples of more general trends, and to explore them in some detail. Readers may or may not agree with the choices presented here, and there are certainly many issues and regions which do not receive the attention they deserve. Yet the book examines a broad spectrum of regional and international developments, emphasizing the role of the superpowers and particularly their relations with the Third World, so that we shall have more than enough to contend with. The narrative highlights political events, and thus provides a foundation for more specialized reading in social and economic history.

Readers will note that I have allotted more space to the Western Bloc than to the former Eastern Bloc. At the beginning of the 1980s there were no more than thirty countries (out of approximately 170 in all) which claimed to be Marxist in some respect (counting several in the Third World), while at the end of the decade the Soviet Union and the Warsaw Pact were on the brink of dissolution and moving towards market reform and political upheaval. As we shall see, Western influences have dominated the history of the post-1945 period, and I have struck a balance accordingly. I have also given a large amount of space to developments in the Third World, because it is home to three-quarters of the worlds population. Moreover, at least 30 million people have lost their lives in wars and other conflicts in Asia, the Middle East, Africa and Latin America since 1945. The history of the Third World is thus central to any study which purports to be global in scope. In addition I frequently reach further into the past and examine events well before the Second World War, in order to provide necessary background. The strength of the historical approach is that it introduces whatever evidence is needed for understanding the issues at hand, whether it is from the same or from an earlier time. There are, of course, other ways of interpreting events besides the views in these pages, but my goal has been to emphasize the specific historical contingencies prevailing in each situation, and thus to explain a variety of different outcomes.

The chapters which follow are a venture in what is called contemporary history that is, the history which blends into our own times and directly affects outcomes today. Many readers will have witnessed some of the developments reviewed here or know of them at least via the media and will hold various opinions about their meaning. Yet even the witness needs to undertake formal study, so as to correct lapses of memory, to acquire new information unavailable at the time and to discover other points of view and thus gain a broader perspective on events.

It is important to remind readers, however, that historians even contemporary historians are not capable of going beyond the present to achieve some kind of predictive power. If anything, history illustrates the hazards of such an undertaking, whether attempted by academics, media seers or others. The revolutionary events of 1989 in Eastern Europe may serve as a warning to those who believe that previous trends can be projected into the years ahead, or that even the near future is readily discernible.

Moreover, the historian must concede that chance events and individual personalities can affect deeply rooted trends, which is another reason for abjuring the role of prophet. For example, as we shall learn, the 1972 Managua earthquake had an important impact on the politics of Nicaragua, exacerbating economic hardship in both city and country and hastening the formation of an effective opposition against the Somoza dictatorship. Seismologists do not have the power to foretell earthquakes, however, and so historians could hardly anticipate that a natural disaster would alter the course of Central American politics. Similarly, accident or fate can remove a leader of apparent importance, with incalculable consequences, the assassination of American president John Kennedy serving as a possible example. The importance of the individual is evident in many other cases as well. Certainly it made a considerable difference that in Iran it was the Ayatollah who succeeded the Shah in 1979 rather than a secular leader, or that in the Soviet Union Mikhail Gorbachev assumed power in 1985 rather than someone cut from the same cloth as a Leonid Brezhnev.