LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

e-ISBN: 978-1-4766-1963-7

2014 Novotny Lawrence. All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

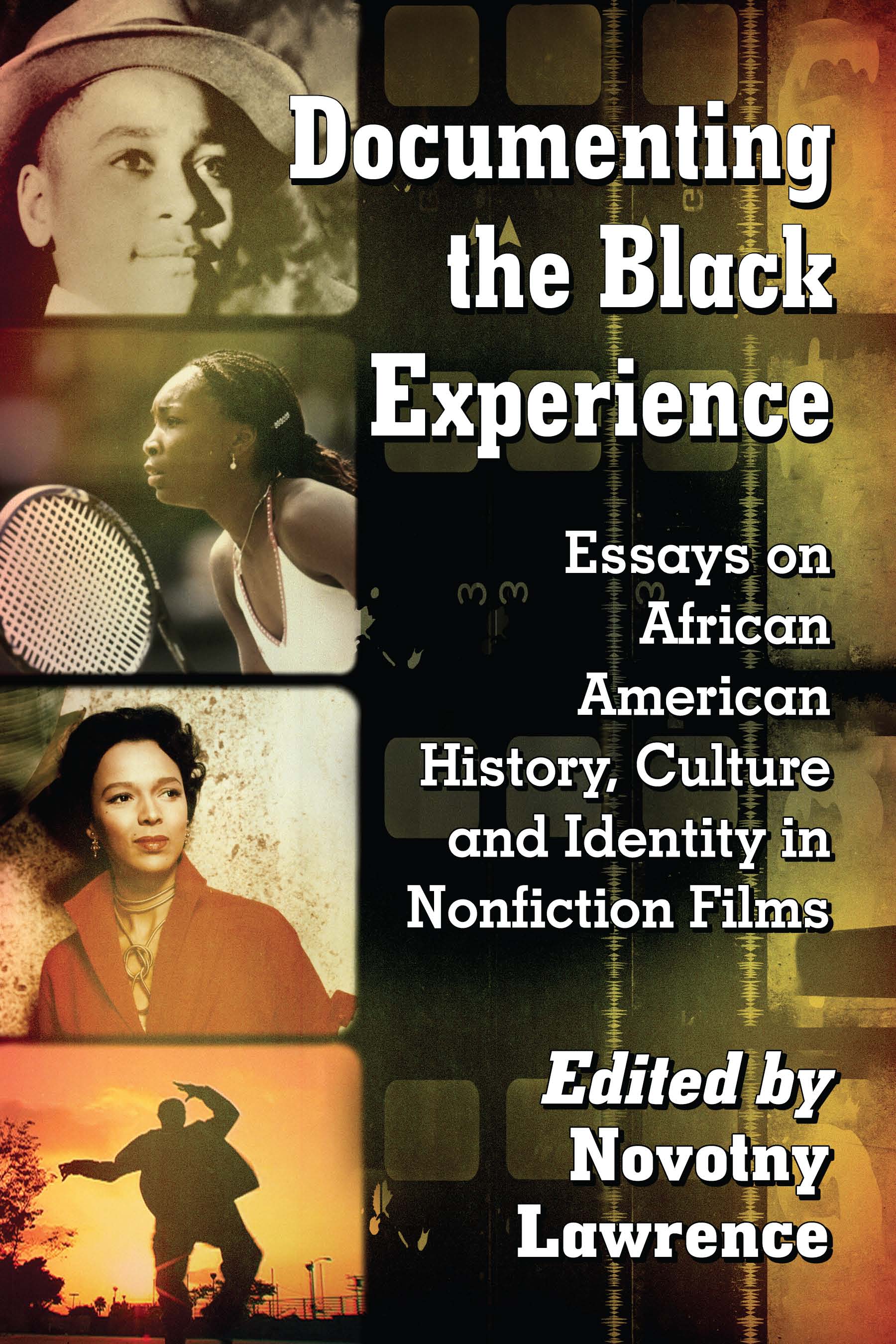

On the cover: top to bottom Emmett Till, The Untold Story of Emmett Louis Till, 2005; Venus Williams, 2000s; Dorothy Dandridge, 1950s; Rize, 2005 (all images Photofest)

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640

www.mcfarlandpub.com

For Louteamer, Bobby, Verdie, and Leanna

Acknowledgments

I would like to begin by thanking all of the contributors to this volume. Bringing this book to fruition has been a long journey, and through it all, the authors were patient and demonstrated a serious commitment to this work. In addition, I express my appreciation for Mary Lou Kowaleski for all of her work on this volume. Her insight and diligence made this collection even better than I could have envisioned.

I also thank my parents, William and Virginia Lawrence, for their love and support. And I thank my brothers, Cornell and Courtney, for their friendship, love, and guidance. Together we have grown from boys to men.

Additionally, I want to recognize my nieces and nephews, Rachael, Cheyenne, Jordan, Andrew, Alexis, and Alyson. Your love and respect mean a great deal to me, and I will continue to forge ahead in the struggle for equality with the hope of making the world a better place for you all.

I also express my deep gratitude to my wife, Sarah Lawrence, for her love and unwavering support. It means a great deal to me to know how much you believe in me and what we refer to as the work. You remain my motivation and mean more to me that I could ever express. Thank you for all that you are.

Further, I want to acknowledge my godmother, Paula, whom we lost in 2013. Although you have left this earth, your caring and giving spirit endure. I will never forget your love and kindness.

I also thank Dr. Dafna Lemish for being a wonderful mentor and for counseling me as I was searching for a publisher for this volume. I greatly appreciate your guidance.

Thanks to all of my colleagues in the Department of Radio, Television, and Digital Media and in the College of Mass Communication and Media Arts at Southern Illinois University. I feel very fortunate to be able to work with such a talented, dynamic, and creative group of people.

I also would like to acknowledge Father Joseph Brown, Professor Kevin Willmott, Dr. Peter Lemish, Dr. Derrick Williams, and Dr. Rachel Griffin for their support and sustained advocacy against oppression. Though the struggle is at times frustrating and difficult, I find great comfort in knowing that we are engaged in it together.

Additionally, thank you to the members of my extended family, who have always loved and cared for me unconditionally.

I want to express my appreciation for Lloyd Ballou, Germaine Brown, David Rooks, Dr. Larry Ehrlich, and Dr. Gregory Black. Your friendship and support mean a great deal to me.

Finally, I thank all of my students for making academe an exciting and fulfilling career.

Introduction

NOVOTNY LAWRENCE

Because issues such as slavery and lynching are key to understanding the African American experience, I often reconsider my K12 education and wonder why such atrocities did not occupy a more prominent space in my history classes. Rather than instruct me and my fellow classmates about such aspects of black life, among the most popular anecdotes that my teachers recounted to the class were that the first president of the United States, George Washington, had false teeth and that he chopped down cherry trees for some reason that I cannot even remember. Although I didnt consider it at the time, as I grew older and progressed further in my education, I found it incredibly disappointing that a teacher would privilege such pieces of information over the fact that Washington had been a slave owner. From my perspective, that kind of information is much more relevant for students as it provides even further evidence of how far-reaching the institution of chattel slavery actually was. While I fully understand that it is impossible for any instructor, class, or school for that matter to cover every detail in history, when I reflect upon my early school years, it is clear that much African American history was either glossed over or simply excluded from the curriculum; my students consistently inform me this is still the case today. That the black experience can be so easily dismissed when it has played and continues to play such a prominent role in the development of the United States always leads me to this questionHow many ways can American society continue to tell African Americans that they are less valuable?

As a result of what I consider to be glaring omissions in my education, I have turned to many different sources to become more informed about the atrocities that have plagued black folk since they were initially transported to the United States against their will. Documentary films are among the most valuable resources for filling in the gaps in history, a point that I set out to share with my students in the spring of 2008 when I taught a course on black-themed nonnarrative film. As I prepared my syllabus, I was thoroughly dismayed when I discovered that there was scant academic literature devoted to examining the black documentary experience. More often than not, scholars discussed African American documentarians either in passing or in stand-alone chapters in anthologies focusing more broadly on nonnarrative cinema. As an example, in his seminal text Documentary: A History of the Non-fiction Film, Erik Barnouw provides little attention to black filmmakers Marlon Riggs and Bill Miles, whose documentaries Color Adjustment (1992) and Liberators: Fighting on Two Fronts in World War II (1992) shed light on the black experience in television and the little-known story of an all-black tank battalion, respectively. Betsy A. McLane follows suit in A New History of Documentary Film.

Importantly, Phyllis R. Klotman and Janet K. Cutlers Struggles for Representation: African American Documentary Film and Video is the sole academic book to date devoted to the black documentary experience. In particular, the text examines more than 300 nonfiction works by more than 150 African American film/videomakers that constitute the burgeoning African American documentary tradition. Indeed, Struggles for Representation is significant as it brings attention to the production, content, and challenges associated with bringing a range of films, including The Negro Soldier (1944), Eyes on the Prize (1987), and Midnight Ramble (1994), as well as many others, to fruition.

Although Struggles for Representation marks an important contribution to documentary literature, much has occurred since its publication in January 2000. Significantly, in the early 2000s nonnarrative cinema experienced a renaissance, in large part due to the box-office success of Michael Moores Bowling for Columbine (2002) and Fahrenheit 9/11 (2004). In addition, technological advancements in the form of digital video cameras and fairly inexpensive home editing software have afforded more documentarians the opportunity to seize the means of production. As a result, there has been an influx of nonnarrative films over the last ten years, many of them, such as

Next page