Contents

Page List

Guide

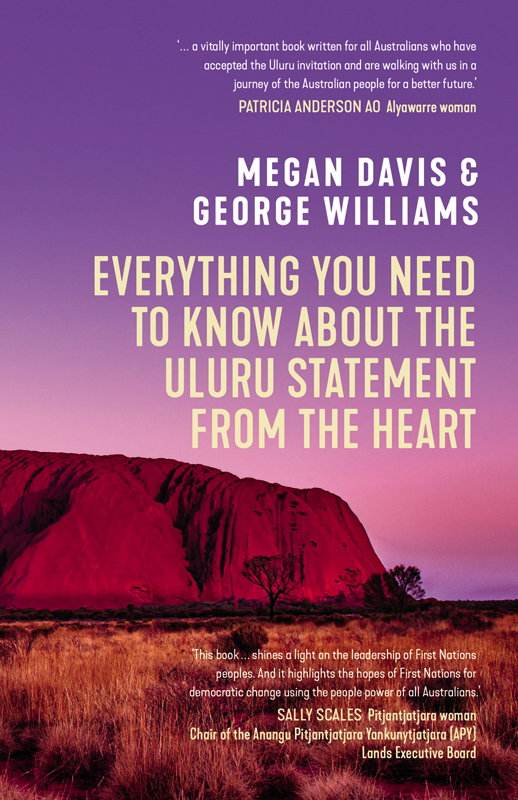

EVERYTHING YOU NEED TO KNOW ABOUT THE ULURU STATEMENT FROM THE HEART

M EGAN D AVIS is the Balnaves Chair in Constitutional Law, Director of the Indigenous Law Centre at UNSW Law and Pro Vice Chancellor at UNSW. She is the leading constitutional lawyer on Indigenous constitutional recognition and was a member of the Prime Ministers Referendum Council and the Prime Ministers Expert Panel on Constitutional Recognition. She is a United Nations expert based in the UN Human Rights Council, Geneva and formerly UN New York. She is a Cobble Cobble woman from south-west Queensland.

G EORGE W ILLIAMS AO is the Anthony Mason Professor and a Scientia Professor, as well as a Deputy Vice Chancellor, at UNSW. He has published books including Australian Constitutional Law and Theory, The Oxford Companion to the High Court of Australia and Human Rights Under the Australian Constitution. He has appeared as a barrister in the High Court of Australia and is a columnist for The Australian.

A UNSW Press book

Published by

NewSouth Publishing

University of New South Wales Press Ltd

University of New South Wales

Sydney NSW 2052

AUSTRALIA

newsouthpublishing.com

Megan Davis and George Williams 2021

First published 2021

This book is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part of this book may be reproduced by any process without written permission. Inquiries should be addressed to the publisher.

ISBN 9781742237404 (paperback)

9781742245300 (ebook)

9781742249865 (ePDF)

A catalogue record for this

A catalogue record for this

book is available from the

National Library of Australia

Cover design Luke Causby, Blue Cork

Cover image Uluru, after the ceremony to mark the permanent closure of the climb in 2019 (photograph by Jimmy Widders Hunt)

Internal design Josephine Pajor-Markus

All reasonable efforts were taken to obtain permission to use copyright material reproduced in this book, but in some cases copyright could not be traced. The author welcomes information in this regard.

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

Recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in the Australian Constitution has attracted national attention for decades. What is all the fuss about? Why have so many people championed the idea? And how do Indigenous peoples want to be recognised in the Constitution?

The final question was answered at an historic gathering of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples at Uluru in 2017. A statement was issued to the Australian people on what constitutional recognition should include. The Uluru Statement from the Heart called for a First Nations Voice to Parliament protected by the Constitution and a subsequent process of agreement-making and truth-telling. This law reform proposal is popularly referred to as Voice, Treaty, Truth.

This call for constitutional reform has a long history in Indigenous communities. One example is Cherbourg in southwestern Queensland. Cherbourg was set up by the Salvation Army in 1899 and became a settlement in 1904 under Queenslands Aboriginals Protection and Restrictions of the Sale of Opium Act 1897.

Cherbourg has conducted discussions on the Constitution on the verandah of the old Ration Shed, the dwelling where small rations of tea, salt, sugar, peas, porridge and flour were given out weekly until 1968.

The symbolism was obvious. In 1901, as Australia embarked on its journey as a new nation with a new Constitution, Aboriginal people were forcibly removed from their country and placed on reserves and missions. Federation meant a loss of rights and freedom for Aboriginal people as they bore the burden of discrimination imposed by law. They were denied the vote, had their children removed, were prevented from marrying, were told where they could live and had their wages confiscated. But a year after a campaign led by many voices from within Cherbourg led to the 1967 referendum that deleted discriminatory references to Aboriginal people from the Constitution, the Ration Shed was closed. To Cherbourg residents, this illustrated the power of the Constitution.

Aunty Beryl Gambrill who was arrested for protesting in 1967 in support of the referendum participated again in 2011 at age 80 in national discussions about constitutional change. She made a submission on the verandah of the Ration Shed, handwritten in pencil, that recognition is important to us and that it should happen as soon as possible. One year later she passed away. Her contribution to equal rights and the community at large was so significant that a condolence motion was passed in the Queensland Parliament.

Some say urgent things are needed in the area of Aboriginal policy and disadvantage, so why focus on constitutional change? Aunty Beryl is an excellent example of why; Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples have themselves identified the need for this reform. They have argued for change since the early years after Federation, in response to their first-hand experience of how the Constitution has impacted negatively on their lives.

They have done so because the Constitution excluded them from the political settlement that brought about the new Australian nation. Rather than being treated as equal citizens, they were cast as a dying race not expected to survive British settlement. They were described as a problem and as a people lacking any future in the nation. This was reflected in the fact that they were immediately denied the vote in federal elections and the Constitution said they could not be included in counts of the Australian population.

The Constitution can seem distant from peoples lives, but it is always there, in the background, shaping the work of parliaments, governments and courts. The Constitution influences our lives from day-to-day, as we saw during the Coronavirus pandemic as the Commonwealth worked with the states to safeguard the community. The Constitution has a long-term, profound effect on the direction of the nation and its laws. The Constitution is the rule book for the nation that:

creates power in Australian society (and so determines who can do what and to whom);

creates power in Australian society (and so determines who can do what and to whom);

establishes the legitimacy of, and relationships between, people and institutions; and

establishes the legitimacy of, and relationships between, people and institutions; and

recognises values and national aspirations.

recognises values and national aspirations.

In each of these ways, the Constitution affects Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and their place within the community.

The advocacy of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples culminated in a successful referendum in 1967. Since then, many people including a long list of Aboriginal people and Torres Strait Islanders and successive prime ministers from Paul Keating and John Howard onwards have agitated for further change. These calls emerged as it became clear that the 1967 referendum had left unfinished business.

The 1967 referendum deleted discriminatory references to Aboriginal people but put nothing in their place. Torres Strait Islanders have never been referred to in the Constitution at all. As a result, rather than recognising Indigenous people, the referendum left a silence at the heart of the Constitution. Today, the document reflects Australias history of British settlement but fails to acknowledge the much longer occupation of the continent by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. It is as if this history does not matter and is not part of the nations story.

A catalogue record for this

A catalogue record for this

creates power in Australian society (and so determines who can do what and to whom);

creates power in Australian society (and so determines who can do what and to whom);