Copyright 2021 by Wil Shelton

All rights reserved. In accordance with the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, the canning, uploading, and electronic sharing of any part of this book without the permission of the publisher is unlawful piracy and theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like to use material from this book (other than for review purposes), prior written permission must be obtained by contacting the publisher at

Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

ISBN: 978-1-7368613-0-1 (Paperback)

ISBN: 978-1-7368613-1-8 (Ebook)

Library of Congress Control Number: 2021910284

Editors: Wil Power Marketing Services

Cover & Interior Design: Juan Roberts / Creative Lunacy

Publisher of Nonfiction Business Books

14742 Beach Blvd. #163

La Mirada, CA 90638

www.wilpowermarketing.com

Printed in the United States of America

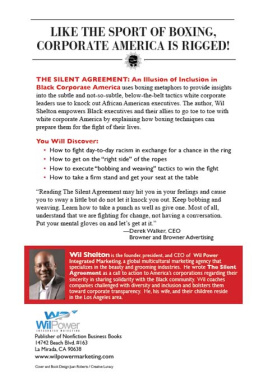

Suppose youve never had a conversation with Wil Shelton one on one; well, here is your chance. Reading the Silent Agreement will give you life and give you a mental workout unlike youve ever had. Each chapter works with another different muscle in your brain. If youve ever felt that corporate America doesnt understand, value, or even appreciate your journey as a person of color. Then this book is for you. My advice is to stretch before you read this book because Wil will not take it easy on you or your feelings.

Keni Thacker

Founder / Chief Creative Officer

Roses From Concrete

IF there is no struggle there is no progress. Power concedes nothing without a demand. It never did and never will.

Fredrick Douglass, 1857

We have been trying to hold a conversation about diversity and inclusion when in actuality, we are in a fight to reach real diversity and inclusion. Wil Shelton draws this out by tying the struggle to achieve inclusion to a boxing match.

All fights are not physical, but that doesnt mean we are not fighting anyway. Wil highlights how our desire to obtain diversity has us in a fight that we have not fully committed to winning, but we can if we shift our mindset from having a conversation to winning a mental boxing match.

You are going to be uncomfortable reading this book. Good. That is the beginning of growth and evolution. To become more inclusive, we have to fight with how we think about others and ourselves, we have to fight to change the systems, policies and practices we have put in place to prevent us from changing.

Reading this book may hit you in your feelings and cause you to sway a little but do not let it knock you out. Keep bobbing and weaving. Learn how to take a punch as well as give one. Most of all, understand that we are fighting for change, not having a conversation. Put your mental gloves on and lets get at it.

Derek Walker, CEO

Browner and Browner Advertising

DING, DING. ROUND ONE.

ROUND 1

Putting on the

GLOVES

IN the early eighties, a street-hardened, 16-year-old kid named Michael Gerard Tyson was left in the legal care of his boxing manager and trainer Gus DAmato after his single mother died. At that time, Tyson trained at the Catskill Boxing Club where Teddy Atlas assisted DAmato in molding a young Tyson into the fearsome heavyweight champion he later became. DAmato and Atlas helped Tyson perfect his signature peak-a-boo style of boxing in which he quickly slips his head out of range of his opponent and moves it from side to side to remain elusive while setting up his offense. Skills like this are what make boxing so fascinating to watch.

Remembering back to those early training sessions, Atlas once said of Tyson, We used to have to pay sparring partners because he punched so hard that he knocked them out. Then every so often wed get one that he couldnt knock out. When the latter happened, Tyson engaged in the silent agreement in which he would lean against his also-exhausted opponent giving both of them a chance to rest. Atlas blamed Tysons habit of making this agreement as immaturity, and he told Tyson to stop doing it. Atlas said to Tyson, Stop making silent agreements. Because one day youll get a guy who wont sign a contract.

As a competitive weightlifter, athlete, and business owner, Ive often thought about the correlations between sports and the fight for racial equity within corporate America. Specifically, Ive noticed that Black executives inadvertently make silent agreements to be content with less, to not fight for what they deserve, and to fully support the demands of the corporate administration even when those demands conflict with their own community, culture, and conscious. Those who comply with these unwritten contracts with corporate America almost always find out the hard way that the other side hasnt signed. Even though African-Americans may stay silent about the day-to-day racism they experience, and they may even help ensure other Blacks stay on the Black track (the path that inevitably leads toward a managerial plateau), they are never rewarded. In fact, they come to feel like psychological contortionists who are betraying their true selves and their own culture to further what they think are their future interests, but with no real payoff.

Research conducted by McGill Universitys Patricia Faison Hewlin shows that many minorities feel pressured to create facades of conformity, suppressing their personal values, views, and attributes to fit in with organizational ones. As Hewlin and her colleague Anna-Maria Broomes found in various industries and corporate settings, African Americans create these facades more frequently than other minority groups and feel the inauthenticity more deeply.

The major disconnect for Black men and women in corporate America is that they experience racism and micro-aggressions in the workplace every day, even as they are told that everyone is on board to combat these corporate conflicts. Many times, when Blacks point out race-related problems, they are punished in ways large and small by white group-think that seems to say, We knew you would cause problems. Were letting you be here. Isnt that enough? A noted psychiatrist once summed it up this way: Those Black executives in the potentially greatest psychological trouble are the ones who try to deny their ethnicity by trying to be least Blackin effect, trying to be white psychologically.

These futile attempts to blend in play out in corporations across America, as Black men and women who are tired of battling micro-aggressions and flagrant discrimination at work simply make a silent agreement to stop fighting. Even those who dont completely stop fighting still dont fight with the same intensity they once did. Instead, they start throwing dont-hit-me punches, because they are no longer trying to win, just mentally survive while waiting for the conflict to be over. Many promising Black executives leave corporate America altogether once they understand that they will never be able to win the ultimate prize: access to corporate C-suites and boardrooms.

Next page