Contents

Landmarks

2022 David Roediger

First published in the United States by OR Books LLC, New York, 2020.

This edition published in 2022 by

Haymarket Books

P.O. Box 180165

Chicago, IL 60618

773-583-7884

www.haymarketbooks.org

ISBN: 978-1-64259-727-1

Distributed to the trade in the US through Consortium Book Sales and Distribution (www.cbsd.com) and internationally through Ingram Publisher Services International (www.ingramcontent.com).

This book was published with the generous support of Lannan Foundation and Wallace Action Fund.

Special discounts are available for bulk purchases by organizations and institutions. Please call 773-583-7884 or email for more information.

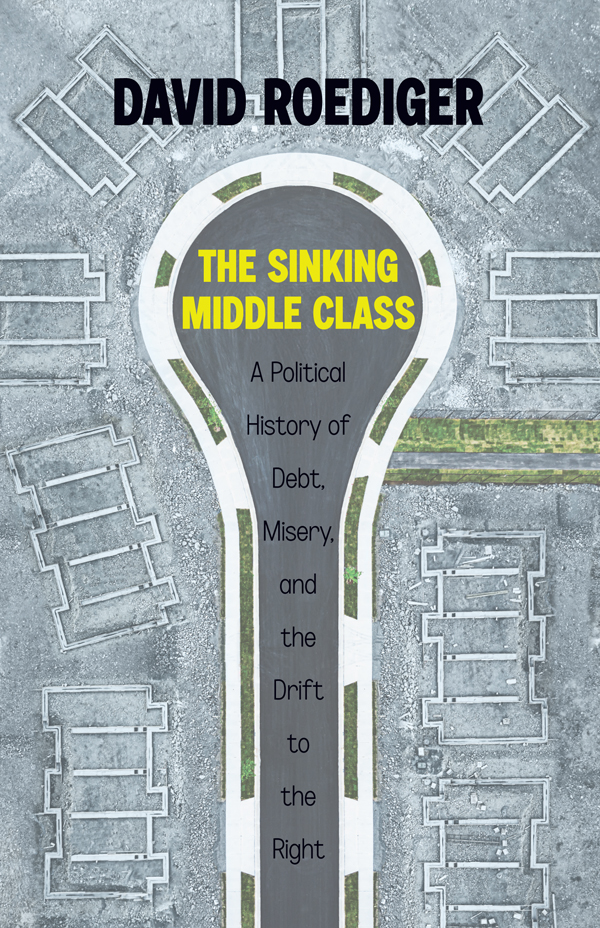

Cover photo of home foundations on a newly paved cul-de-sac captured by aerial drone, Getty images. Cover design by Eric Kerl.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data is available.

And then perhaps this misery of class-prejudice will fade away, and we of the sinking middle classthe private schoolmaster, the half-starved free-lance journalist, the colonels spinster daughter... the jobless Cambridge graduate, the ships officer without a ship, the clerks, the civil servants, the commercial travelers, and the thrice-bankrupt drapers in the country townsmay sink without further struggles into the working class where we belong, and probably when we get there it will not be so dreadful as we feared, for, after all, we have nothing to lose but our aitches.

GEORGE ORWELL, journalist and socialist

PREFACE

My childhood taught me that the middle class could be both a site of extreme misery and the location for labor militancy. That upbringing made it logical that I would write this book, questioning as it does the idea that the middle class ought to be saved as an unambiguously good thing in US society and proposing that the practice of separating it, as a category, from the working class should be abandoned.

My grandfather on my fathers side had a good working-class job, a concept that has decreasing meaning to young people as unions dwindle. He worked in a quarry in a strongly unionized area. Three of his sons had similar blue-collar jobs, in printing, electrical work, and pipe fitting. My dad bucked that trend. Clever and good with numbers, he took a white-collar job at the quarry after naval service in World War II. Being employed in the office meant he was not in the union. He kept the books in the companys headquarters, right next to where limestone was crushed. He shared office space with the quarrys owner and his son, the companys heir apparent. In the next room, several other clerks and technical workers toiled. The owners came and went at will; my dad clocked in and out. The owners showily kept copies of Playboy on their desks. My dad increasingly smuggled in whiskey bottles, having just enough unsupervised time, and for a while enough wits, to drink while doing a thankless, demanding job scrutinized by two bosses, each not ten yards away. That setup helped to kill him before age fifty. The owners dressed expensively in what would later be called business casual attire. My dad literally wore white collars, spending a fair amount to signal success. He was upwardly mobile. Nevertheless, materially, and most of the time spiritually, he fared far less well than his relatives in the skilled trades. He held a working-class job that required a middle-class costume and carried with it specific sets of sadnesses.

My mother, orphaned by age five, lost her mother after the birth of her twin brothers, and her fathertogether with his substantial income from a very good working-class job as a unionized railroad workerin a work accident. Raised by a grandmother and two aunts, she came from a family that also rose to the middle class and declined materially. One aunt processed accounts for a coal company; the other was a longtime telephone operator, a job eventually unionized and waged rather than salaried, but nevertheless carrying requirements of education and diction that placed it in a contradictory and highly gendered class location. Those mentors made sure that my mom studied for two years in a teachers college before she reached nineteen. She had taught grade school for a quarter century before she graduated from college, taking a course whenever she could. She made even less money than my dad. The professional organization that she joined saw teaching as a respectable middle-class profession. It arrayed itself against unions and strikes until nearby work stoppages by militant unions attracted raises and imitators. By mid-careershe taught forty-nine years my mother was a local union and strike leader. It was only then that she secured something like what was considered a middle-class income.

The association of the middle-class job with misery and working-class struggles with forward motion thus came very early to me, certainly before I knew anything of the exact terminology. A particularly painful early memory was of an extended family fishing trip designed, I now realize, to remove my dad from the fact that had he not taken vacation, he would have been expected to work during a labor dispute at the quarry. Not unconnected to this mix was the direction of my own political maturation during the anti-war and Black freedom movements, during which I continually found my way to currents emphasizing the role of the labor movement in social transformations.

None of this made for sustained consideration of the middle class. I thought of college teaching as a working-class job. My university work remained insecure into my mid-thirties and low-paid enough for another decade and more that family and friends with good union jobs wondered at the folly of academic work. My own fortunes brightened as universities decided to overpay a few designated star faculty at the same time that they imposed neoliberal austerity, underpaying the rest of those teaching and increasing insecurity in employment. Such changes hardly altered the fact that that seeing academic labor as middle class contributed to making faculty vapid and powerless. Over the course of my long career, it became clearer to me that universities were soul-killing places to work. Moreover, my research came to focus partly on labor history and working-class studies, fields whose attention to the middle class often stops at the worried observation that far too many of us who are really working class are bamboozled into middle-class self-identification. This book comes out of reflection on such bamboozling, particularly in US politics. However, the work of researching it convinced me that middle-class consciousness among working-class people is a deeply complex matter, rooted in material experiences, including ones of extraordinary misery, as well as in getting fooled by ideologues and advertisers and bribed by petty privileges.

I became interested in the middle class in the early 1990s with the extraordinary rise of political appeals to save the middle class, largely from the Democratic side. At the time, my writing mostly tackled the history of the white worker, a potent pairing of words that disfigured thinking about class in the long run of US history. But as I wrote, the ascending Clinton wing of the Democratic Party released a raft of appeals to the presumptively white middle class into the hot air of presidential politics. It did so in such a way as to loosely pair emphases on the middle class with less frequent but disturbing appeals to an explicitly white working class. The problem of placating the right-leaning Reagan Democrat, learned about almost ethnographically from focus group interviews amplifying his worst racist impulses, became the great necessity for progressive electoral politics. The formula ultimately offered little to constituencies of colora stance its advocates adopted on the grounds that to do so would risk electoral defeats caused by an alienated white middle class. This dovetailed nicely with appeals to the latter, not in terms of concrete pro-worker policies, but instead in terms of listening to racialized complaints about welfare, taxes, and crime.