First published in 1964 by Oxford University Press for the International African Institute.

This edition first published in 2018

by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon 0X14 4RN

and by Routledge

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

1964 International African Institute

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Trademark notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 978-0-8153-8713-8 (Set)

ISBN: 978-0-429-48813-9 (Set) (ebk)

ISBN: 978-1-138-59421-0 (Volume 29) (hbk)

ISBN: 978-0-429-48898-6 (Volume 29) (ebk)

Publishers Note

The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality of this reprint but points out that some imperfections in the original copies may be apparent.

Disclaimer

The publisher has made every effort to trace copyright holders and would welcome correspondence from those they have been unable to trace.

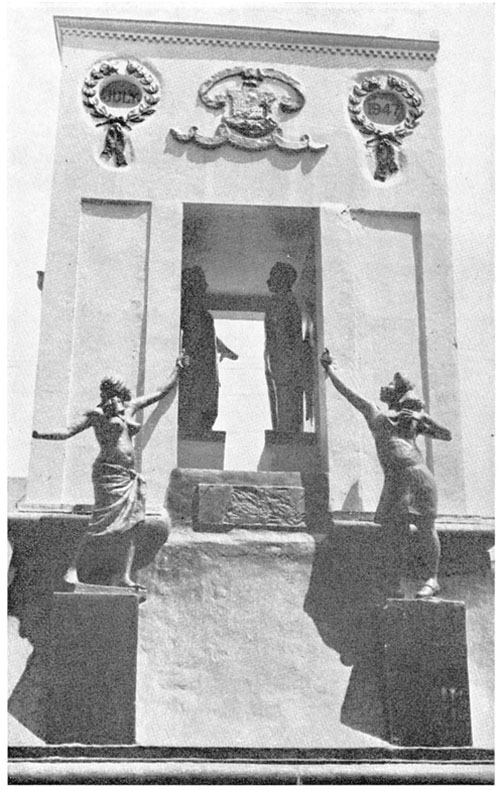

Centennial Memorial: the first and present Presidents flanked by figures representing tribal and civilized women

TRIBE AND CLASS IN MONROVIA

BY

MERRAN FRAENKEL

Published for the

INTERNATIONAL AFRICAN INSTITUTE

by the

OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS

LONDON IBADAN ACCRA

1964

CONTENTS

Oxford University Press, Amen House, London E. C. 4

GLASGOW NEW YORK TORONTO MELBOURNE WELLINGTON

BOMBAY CALCUTTA MADRAS KARACHI LAHORE DACCA

CAPE TOWN SALISBURY NAIROBI IBADAN ACCRA

KUALA LUMPUR HONG KONG

International African Institute, 1964

Printed in Great Britain by

The Alden Press Ltd., Oxford

T HE Republic of Liberia is, apart from Ethiopia, the oldest independent state in Africa, having had its own constitution since 1847. It is a small countryin area 43, 000 square miles, in population less than two millionsbut the peculiarities of its history and social structure make it an area of unique sociological interest. For it has no history of rule by a colonial power. Its government has, at least until recently, been in the hands of a small minority composed of Negro immigrants from America and their descendants, who are commonly known as Americo-Liberians, while the bulk of its population is made up of the members of about twenty indigenous tribes. During the first century of the republics existence, interaction between Americo-Liberians and tribespeople produced a caste-like social system. However, since the Second World War, Liberia like other African territories has been through a period of unprecedented economic growth and social change. This study seeks to analyse how, during the present period of transition, a new and more open system of social stratification, more akin to a social class system, is appearing in Monrovia, the republics capital and only sizeable city.

Such analysis can be meaningful only if viewed from the perspective of Liberias peculiar history. Since the Liberian Republic is one of the most inadequately documented of all African countries, I start with an outline of the circumstances of its founding and of the main factors which determined its development during the first century of its existence. Chapter II describes present-day Monrovia: its sprawling physical lay-out; the main features of its population, today totalling over 53, 000; its economic structure; and the manner in which it is administered. It has no large scale employers, a high proportion of self-employed persons, and a great deal of casual labour. There is no formal, overall administrative system, and government policy towards such matters as immigration and housing may be characterized as laissez-faire. In this situation, tribal and kinship bonds are particularly significant. Chapter III deals with the urban tribal communities, their history and organization, and the operation of urban tribal courts. I have here as in later chapters focused attention on the Kru tribe. The composition and role of households, and in particular of large extended family households in New Krutown, are discussed in Chapter IV. Chapter V analyses the role of the Christian churches, and of certain other types of voluntary association, and also shows why their membership tends to correspond with, rather than cut across, the general divisions of the population according to both class and tribe. Finally Chapter VI returns to discuss in more detail the process by which a new system of social stratification is emerging, the nature and extent of social mobility, and the present relationship of ethnic grouping to the social hierarchy.

The fieldwork on which this study is based was carried out in Monrovia between April 1958 and April 1959, while holding a fellowship from the International African Institute. I have, for the sake of simplicity, used the present tense, which should be understood as referring to the years 19589. For the first two months of my stay I lodged in a Liberian household in the area to which I have referred as the Town Centre. Subsequently, I spent three months caretaking two houses in succession on fashionable Mamba Point, then I moved to the community of stevedores and dockworkers in New Krutown. This nomadic existence had the advantage of providing me with first-hand experience of life in three quite different types of residential area. To my landlady, my neighbours, and my other good friends in each community, and especially to the Kru Governor and his councillors, I owe sincere thanks for their helpfulness and their hospitality. Between September and December 1958 I taught social anthropology to the senior class at the University of Liberia, and during the following semester I gave a course in English composition at one of the night schools in the town. Conversations and discussions with both groups of students were of great help in giving me insight into their lives and problems. The members of the university class were also of practical assistance in carrying out the questionnaire study of members of voluntary associations, to which reference is made in Chapter V.

I spent a great deal of time, especially during the first months of my stay in Monrovia, searching for documentary material detailed departmental reports, reports of commissions of inquiry, recommendations of committees, and so onof the type with which I was familiar from British territories. In fact, very little documentation of this kind exists. In British territories, much of the impetus for the recording of such material was provided by the obligation to report to the colonial government. In Liberia such impetus has been lacking, and, moreover, Liberians do not share the Britishers reverence for carbon paper and filing cabinets. Indeed, a great deal of the administration of the town, as is apparent from Chapters II and III, is carried out on an