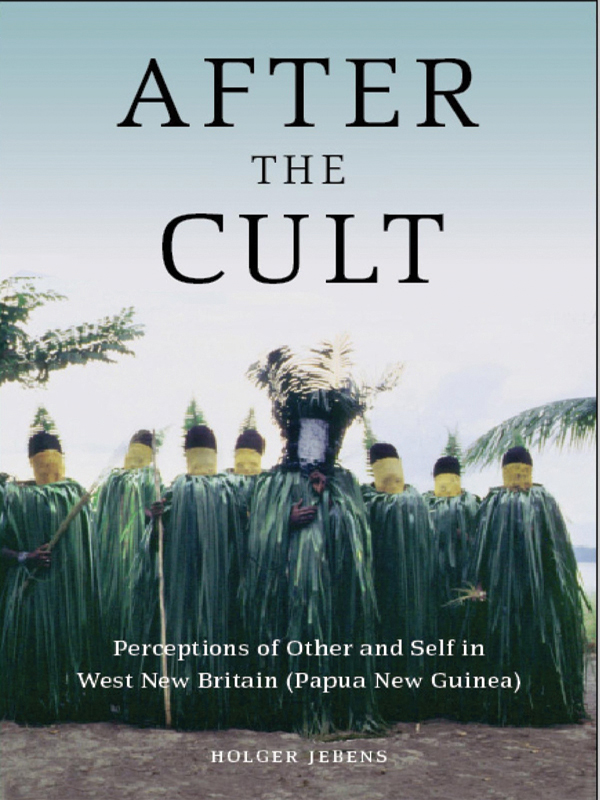

AFTER THE CULT

Perceptions of other and self in West New Britain

(Papua New Guinea)

Holger Jebens

Berghahn Books

New York Oxford

First published in 2010 by

Berghahn Books

www.berghahnbooks.com

2010, 2013 Holger Jebens

First paperback edition published in 2013

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purposes of criticism and review, no part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without written permission of the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Jebens, Holger.

After the cult: perceptions of other and self in West New Britain (Papua New Guinea) / Holger Jebens.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-84545-674-0 (hbk.)ISBN 978-0-85745-798-1 (pbk.)

1. Cargo cultsPapua New GuineaNew Britain Island. 2. PapuansPapua New GuineaNew Britain IslandPsychology. 3. PapuansPapua New GuineaNew Britain IslandAttitudes. 4. Self-perceptionPapua New GuineaNew Britain Island. 5. WhitesPapua New GuineaNew Britain IslandPublic opinion. 6. Public opinionPapua New GuineaNew Britain Island. 7. New Britain Island (Papua New Guinea)Social life and customs. I. Title.

GN671.N5J42 2010

306.6'999212-dc22

2010006693

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Printed in the United States on acid-free paper.

ISBN: 978-0-85745-798-1 (paperback)

eISBN: 978-0-85745-831-5 (retail ebook)

List of maps and figures

Maps

Figures

Acknowledgements

The present work is based on the research project Constructions of cargo: on coping with cultural otherness in selected parts of Papua New Guinea, generously sponsored by the Volkswagen Foundation.

I would like to thank the relevant authorities in Papua New Guinea for providing me with a research permit. Members of the following institutions have kindly supported my work: the Archives of the Missionaries of the Sacred Heart (Mnster and Hiltrup), the Michael Somare Library (Port Moresby), the National Archives of Papua New Guinea (Port Moresby), the National Museum and Arts Gallery (Port Moresby), the Pacific Manuscripts Bureau (Canberra) and the University of Pennsylvania Museum Archives (Philadelphia). In addition, Fr. Reiner Jaspers made available materials from the Archives of the Archdiocese of Rabaul (Vunapope).

Karl-Heinz Kohl has accompanied my efforts over a long period of time and in various capacities, as initiator and supervisor of the research project mentioned above, as a fellow traveller and visitor in Papua New Guinea, and as a demanding but also helpful superior at the Frobenius Institute (Frankfurt am Main) and the New School University (New York). My thanks go to him as well as to others who have also supported me with both friendly interest and critical advice: Brbel Hgner, Dan Jorgensen, Joel Robbins, Hartmut Zinser, and above all Susanne Lanwerd, from whose perceptivity and understanding I have profited greatly.

The photographs were printed by Peter Steigerwald and the maps prepared by Gabriele Hampel. Astrid Hnlich, Dirk Lang and Robert Tonkinson did a preliminary proofreading of the text. I also thank Robert Parkin for his help in translating the German manuscript. This translation was made possible in part through a grant from the Hahn-Hissink'sche Frobenius Foundation.

Lastly and most of all, however, I would like to thank the inhabitants of Koimumu and the surrounding area, and in particular, Francis Ave, Peter Mape, Titus Mou, Otto Puli, Augustin Sande, Joe Sogi and Alphonse Mape, who became a good friend of mine. Many of my interlocutors have insisted that I do not make village and personal names anonymous. It is out of respect and gratitude that I agree to this request, especially as I feel that there is no danger of anyone being harmed by my doing so. Without the hospitality and helpfulness on the part of the inhabitants of Koimumu and the surrounding area, the present work would never have come to fruition: taritigi sesele.

1

Introduction

Topic of research

Kago and kastom

The period of colonisation and missionisation in Melanesia has long since become part of the past. Papua New Guinea achieved independence as a state more than a quarter of a century ago, and in many places white people exist only in the memory or the imagination. Dealing with cultural difference, however, has in no way lost its significance. What Joel Robbins (2004a: 171) states with respect to the Urapmin of Sandaun Province certainly applies to most other societies in the region as well: the opposition of black and white skin is now as important in organizing thought as are those other classically Melanesian dichotomies, male/female, kin/affine, and friend/enemy.

In the context of the present work, I examine cultural perceptions of Other and Self, particularly with reference to indigenous constructions of kago and kastom. Both terms come from the neo-Melanesian Tok Pisin, a lingua franca that emerged towards the end of the nineteenth century in the context of the plantations and the stations of the colonial administration and the missions, and is now widespread in many parts of present-day Melanesia.

Like the similar-sounding word cargo, kago signifies consignments of industrially manufactured Western goods brought by ship or aeroplane, which, from the Melanesian point of view, are likely to have represented a materialisation of the superior and initially secret power of the whites.

Like kago, kastom refers to both verbally expressed ideas and observable actions. In this sense, theoretical and practical constructions of kago and kastom respectively can be distinguished. However, while in the case of kago cultural perceptions of the Other are foregrounded, in the context of kastom this is mostly a matter of the objectification of one's own traditional culture, that is, of cultural representations of the Self. One of the reasons why kastom has established itself in the corresponding literature might be that, unlike vaka vanua, fa'aSamoa, Maoritanga or other locally used terms, it sounds much like the English word custom.

Following an analysis of indigenous constructions of kago and kastom, I compare indigenous and Western perceptions of Other and Self, the latter being articulated in previous research on these constructions. With respect to the view of the cultural Other, Roy Wagner (1981: 31) already suggested such a comparison in the 1970s when he wrote:

If we call such phenomena cargo cults, then anthropology should perhaps be called a culture cult, for the Melanesian kago is very much the interpretive counterpart of our word culture. The words are to some extent mirror images of each other, in the sense that we look at the natives cargo, their techniques and artefacts, and call it culture, whereas they look at our culture and call it cargo.