For our mentors

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS

New York

www.nyupress.org

2016 by New York University

All rights reserved

References to Internet websites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing. Neither the author nor New York University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or changed since the manuscript was prepared.

ISBN : 978-1-4798-4016-8 (hardback)

ISBN : 978-1-4798-8469-8 (paperback)

For Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data, please contact the Library of Congress.

New York University Press books are printed on acid-free paper, and their binding materials are chosen for strength and durability. We strive to use environmentally responsible suppliers and materials to the greatest extent possible in publishing our books.

Manufactured in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Also available as an ebook

Success, Failure, and Everything in Between

J. Jack Halberstam

Sporting events are testing grounds for all kinds of assumptions about race, class, gender, and sexuality. And indeed, most people have a story to tell, when the topic of sports comes up, about their successes or failures in instances of intense competition or about losing their sense of power and strength in relation to all kinds of scenarios in team sports that favor the big, the tall, the strong, the normative. Sport, indeed, offers fertile ground for the crafting and sustaining of racial and gendered stereotypes and it offers a language or a grammar even for thinking about competition and bias. We adapt phrases from sports to describe fairnessa level playing field, for exampleand we go to sports to single out the disastrous effects of cheatingprofessional cycling, for example. Sport offers us a seemingly endless supply of inspirational narratives of the underdog, evolutionary narratives of size, strength, and the survival of the fittest, and surprising narratives about performance and play. And far from offering a neutral terrain for individual competition, sport has, in the last century, provided an arena for a whole array of contests within which national identity, race, sexuality, and gender hang in the balance.

In my work I have tried to understand the dynamic relation between winning and losing, succeeding and failing that make up any sporting event. As I argue in The Queer Art of Failure (2011), a culture oriented to only very narrow models of success relegates entire groups of people to stigmatized failure. But, as sporting competitions reveal, the distance between winners and losers is often only inches or seconds. Sport, more than most arenas of popular culture, offers us a chance to experience both the joy of victory and the agony of defeat. Indeed, even to play sport one must accept defeat as a likely outcome and must fold failure into the experience of competition itself. But of course these notions of success and failure are not value free and not neutral. Racial difference marks our relations to success and failure and even to what we understand these terms to mean in ways that have massive consequences for all who play sport, all who watch sport, and all who recognize sport as allegorical terrain for other kinds of contestations.

For example, historians like Gayle Bederman have used sport, boxing specifically, to highlight the contested arena of racialized masculinity at the turn of the last century. And so, in her book Manliness and Civilization: A Cultural History of Gender and Race in the United States, 18801917 (1996), Bederman opens with the famous boxing match between African American champion Jack Johnson and the so-called Hope of the White Race, Jim Jeffries, in 1910. Cast as a struggle between white and black manhood, this fight led to white riots when Johnson emerged victorious and Jeffries was beaten to the ground. Black fighters from Jack Johnson to Muhammad Ali to Mike Tyson have rarely been allowed to enjoy their success and instead they have been hounded, policed, punished, and demonized.

For women, sport has offered another kind of test. As we saw in the last few years in relation to the runner Caster Semenya, strong, muscular female athletes, particularly those who are nonwhite or non-Western, have been suspected of gender transgressions and subjected to repeated and confusing tests to determine their sex. While the various athletic boards that have tested athletes over the years have used a myriad of methods from cheek swabs to genital examinations, most of these boards have failed to come up with clear guidelines for gender norms in relation to the athletic female body. More recently, calls have been made to bring such testing to an end.

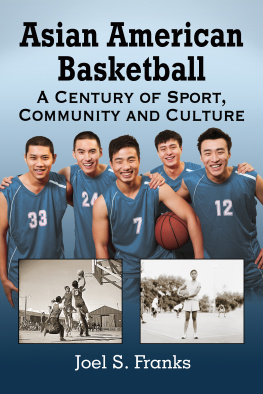

Obviously, sport competitionswhether running, weightlifting, swimming, gymnastics, team sports, or tennisoffer a setting and an opportunity for all kinds of cultural contests to play out. And while the most visible such contests in the last century have involved black versus white bodies (as in boxing) or East versus West (as in gymnastics in the Cold War era), little attention has been paid to other modes of racial formation that unfold quietly and without much fanfare in sporting arenas around the country. As a few of the essays in this collection mention, the Linsanity that greeted the surprising rise and fall of Asian American basketball player Jeremy Lin in the NBA in 2012 revealed a wealth of unexamined narratives about Asian and Asian American bodies within the national imaginary of sport and competition. As Oliver Wang writes: The stock story of Lins rise becomes a seductive affirmation of the American Dreams attainability (despite the fact that its called a dream). However, as Lin is also Asian American, the framing of his accomplishments within the American Dream narrative aligns all too well with another deeply embedded stock story around American race relations: the Model Minority Myth (MMM). As Wang shows clearly in his analysis of the media coverage of Jeremy Lin, as much as stereotypes of Asian American masculinity and athletic ability were challenged and reconsidered in this moment of high visibility, so other stereotypes of conformity and docility were imposed within a wide array of coverage.

Increasingly in contemporary media, sport serves as a shorthand for long standing myths about the nation. Whether we are watching Serena Williams being booed at a tennis competition for yelling at a lineswoman, or listening to some supposedly neutral sports commentator deploy well-worn racial epithets to describe an athlete of color, we can see clearly how sport allegorizes race and buttresses narratives of racial difference. This volume on Asian American Sporting Cultures makes an incredibly important intervention into the current marketplace of ideas about athleticism, race, gender, and performance. It helps us to locate the nexus of assumptions about race and gender as they play out in sport competitions and these essays allow us to grasp the complex histories of racialization that are swept up into banal narratives about uplift or sinister narratives about ability and aptitude.