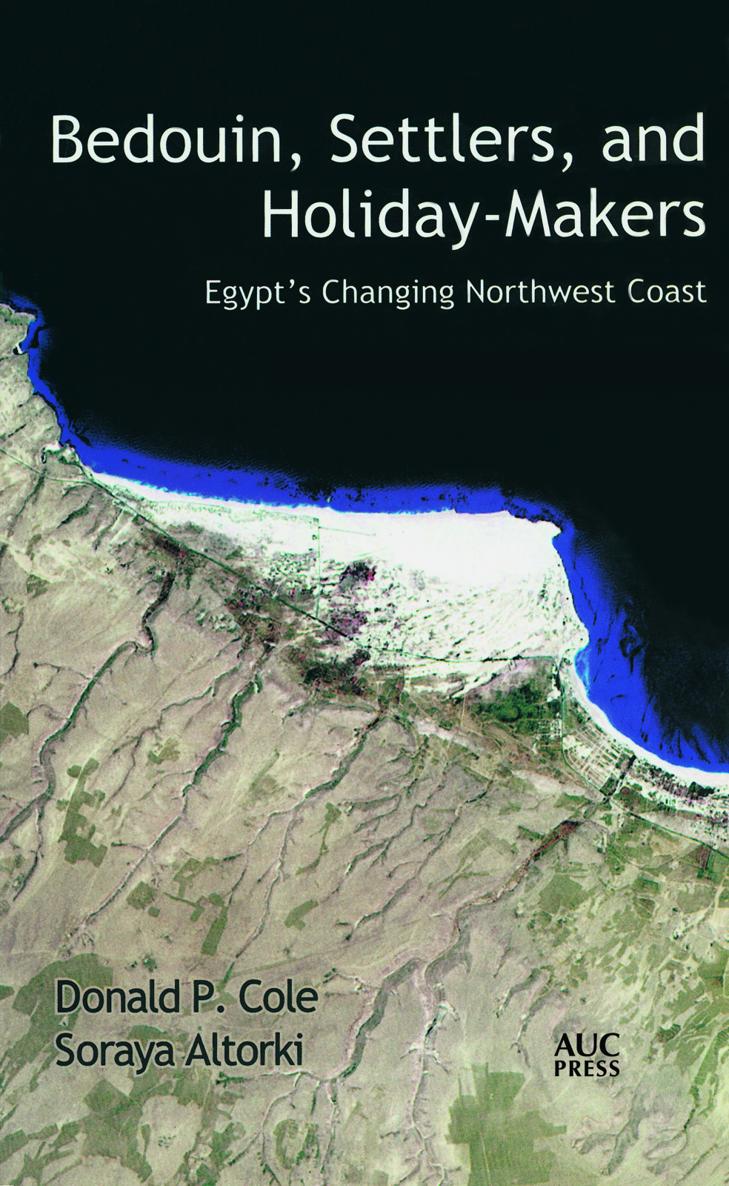

BEDOUIN, SETTLERS, AND HOLIDAY-MAKERS

BEDOUIN, SETTLERS, AND

HOLIDAY-MAKERS

Egypts Changing Northwest Coast

Donald P. Cole

Soraya Altorki

___________________________

The American University in Cairo Press

Copyright 1998, 2014

by The American University in Cairo Press

113 Sharia Kasr el Aini, Cairo, Egypt

420 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10018

www.aucpress.com

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the American University in Cairo Press.

ISBN 978 161 797 361 1

Preface to the Electronic Edition

The authors of this book are an American male and a Saudi Arabian female, both long-term professors of anthropology at the American University in Cairo. Each of us has field research experience in Egypt and Saudi Arabia since the late 1960s in both Bedouin and urban communities, with particular concern for the complex socioeconomic structures that link nomadic, rural, and urban people in regional settings within different Arab states.

The Bedouin of this study are from Egypts largest tribe, the Awlad Ali, who predominate in the northern part of the Western Desert and have relatives in eastern Libya. The settlers are Egyptians from the Nile Valley who have taken up residence in the area, especially since the 1950s, as government employees, teachers, development personnel, traders and business people, hotel owners and workers, and military and police forces. The holiday-makers are mainly Egyptians from Alexandria, Cairo, and Delta citiessome of whom are from the economic elite and others from the middle classes, as well as university students.

During the course of the research, people (mainly men) in Marsa Matruh and villages and settlements to the west of Marsa Matruh were jointly interviewed by the authors, usually in social settings with others. The interviewees recounted from their own perspectives the history of their involvement in the area, their relationships with others in the community, their experiences with government programs in rangeland production, farming, and other fields, the history and development of tourism in the area, and similar topics related to the development process.

Issues about the ownership of land, relations between the army and traditional or customary patterns of land ownership, the overdevelopment of tourism villages along the coast, land degradation and desertification, and local community development permeate the study.

Significantly, the area of this research is halfway between Alexandria and the EgyptianLibyan border and is thus relevant not only to Desert Egypt but to eastern Libya as well. Moreover, the material provides an excellent source of comparative perspectives for Sinai and the Red Sea Eastern Desert, which have Bedouin, towns, and foreign and local tourism development.

February 2014

CONTENTS

PREFACE

We are an Arabian woman and an American man, and also anthropologists who met in the 1960s as graduate students at the University of California, Berkeley. We now work as colleagues at the American University in Cairo (AUC), where Cole has taught since 1971 and Altorki since 1977. Moreover, we separately pioneered modern social anthropological research in Saudi Arabia, as Cole studied the A1 Murrah Bedouin in the arid ranges of the Empty Quarter and Eastern Province in 1968-70 and Altorki first conducted research in 1971-73 among elite families of the urban community of Jiddah in the Hijaz or Western Province (Cole 1975; Altorki 1986).

In the mid-1980s we decided to work jointly to study change and development in Saudi Arabia as that process had unfolded in a specific community; and thus in 1986-87 we conducted fieldwork inUnayzah, a small city and oasis in the Qasim region of Najd, Saudi Arabias arid central province. That research showed the ancient existence of complex organization in desert Arabia, where urban-based markets had linked nomadic pastoralist production, sedentary farming, and craft work into common exchange systems at the level of local regions. These markets had also organized long-distance trade which tied Arabias regions to other parts of the world. ForUnayzah and the region of Qasim, these other parts of the world were mainly greater Syria, Iraq, Egypt, and western India.

Our work documented the gradual decline of Arabias old political economy during the first three or four decades of the twentieth century, as the introduction of new technologies and the rise of the contemporary Saudi state brought significant change. A period of change that we characterized as substantive development took place during the 1950s, 1960s, and early 1970s. However, the boom that resulted from Saudi Arabias acquisition of large amounts of revenue from the sale of oil beginning in the mid-1970s brought change of transformational proportions: a major expansion of new agriculture in the desert; a massive construction of new housing and physical infrastructure; a rapid expansion in education and occupational change for men and women; and a vast importation of expatriate workers, consumer items, and machines and their spare parts. This transformation brought high standards of living to most of the local population; but we questioned the sustainability of many aspects of the change and posited that the boom had marked a truncation of many of the development achievements which had preceded it (Altorki and Cole 1989; Cole and Altorki 1992,1993).

The present study continues the joint work we began inUnayzah; but the location this time is the arid ranges, dryland farming areas, desert beaches, and small provincial capital of the Matruh governorate in Egypts northwest coastal zone. Many differences exist between communities in central Arabia and those in northwest Egypt.Unayzah, for example, is more hadar,urban,and the northwest coast more badiya,Bedouin.Yet the overall process of change in both areas demonstrates many similarities despite different local histories and economic specificities, and important parallels exist between the two cases. Moreover, change underway in the northwest coast is more than just a local regional phenomenon within the governorate of Matruh. The transformation there is part of processes that, in some instances, are specifically related to Egypts national political economy and, in others, more generally to development in similar desert regions of the wider Arab world.

Our selection of Egypts northwest coast as the location of this study is the result of a combination of personal, practical, and academic or scientific factorsas is probably the case for most research projects. The Arabian Peninsula will always occupy a special place in our minds and hearts, but we have also long wanted to conduct academic research in the Egypt that has provided us with employment and with residences that have become homes for each of us. The exquisite beauty of the sea and the many excellent beaches in this part of Egypt, quite frankly, also enticed us to the area. Marsa Matruh, the regions administrative capital, is an easy drive of about five hours by car or bus from Cairo, and we could readily travel there for shorter and longer durations of fieldwork. Also, we had previously spent individual holidays in the area, and each has nostalgias that go back twenty and more years and provide us with personal links to the northwest coast.