Anthem Press

An imprint of Wimbledon Publishing Company

www.anthempress.com

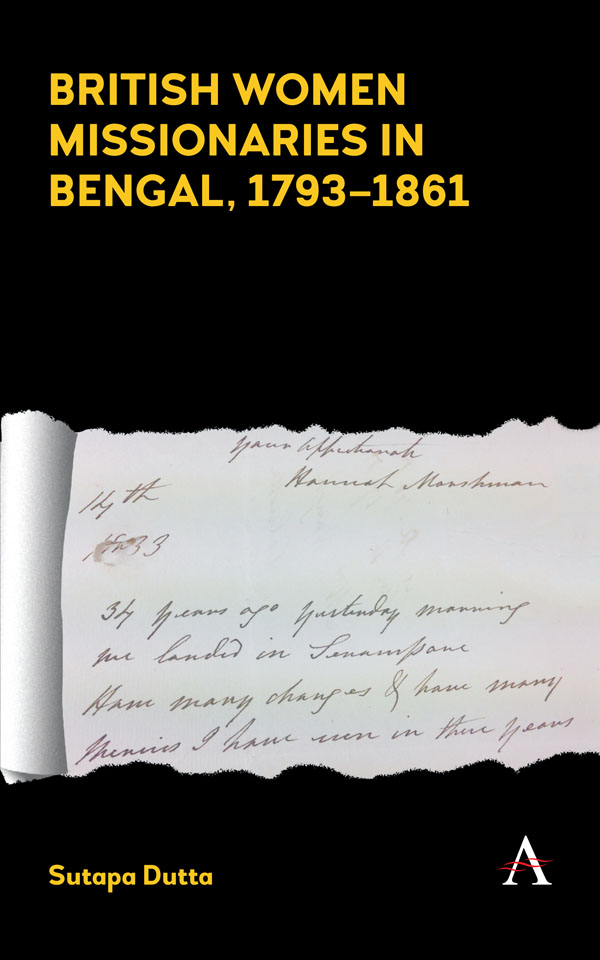

This edition first published in UK and USA 2017

by ANTHEM PRESS

7576 Blackfriars Road, London SE1 8HA, UK

or PO Box 9779, London SW19 7ZG, UK

and

244 Madison Ave #116, New York, NY 10016, USA

Sutapa Dutta 2017

The author asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN-13: 978-1-78308-726-6 (Hbk)

ISBN-10: 1-78308-726-9 (Hbk)

This title is also available as an e-book.

This book was begun at a very difficult and unhappy time as I saw my mother battling and losing out to a difficult illness. The months after her death were a vacuum, a hard reality in which writing this book has been as much an exercise in self-realization as it has been cathartic. As someone who inspired her daughters to realize their worth, I owe everything to her.

It is a happy coincidence that many women have helped me write this book on women missionaries. To begin with, I am greatly obliged to the missionary sisters and the nuns who were responsible for moulding my formative years in school and college. I have only tried to emulate their dedication, discipline and devotion to work. The book is a grateful acknowledgement of their teaching and service to others.

An Early Career Fellowship provided by the International Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies (ISECS) and Manchester University greatly facilitated the process of writing this book. It provided a stimulating academic environment where discussions with like-minded colleagues from all over the world forged deep bonds of the mind and heart. I am specially grateful to Penny for her intellectual input and encouragement. A chapter written for a book edited by another special friend, Christina Smylitopoulos, forms the basis of the first chapter of my book. A conference organized at Oxford University by the British Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies (BSECS) further provided me with a grant and a platform to read out a paper on this topic. The book was to eventually develop from this conference paper. I am thankful to the publishers for commissioning this book, to the unknown reviewers for their valuable suggestions and to the editorial department, especially Abi and Vincent, who have always responded with alacrity and professionalism.

My students and colleagues, former mentors and teachers have been pillars of strength, with their suggestions, research materials or just emotional support whenever I needed it. I am particularly indebted to Dr Meenakshi Jain, with whom the long sessions of discussions would frequently spill into hours in the corridors and even parking lots. Her knowledge on the subject and the intellectual stimulation she provided have often been the most exciting reasons was sown by her many years back.

The research would not have been complete without the assistance of librarians and archivists, some of whom have gone out of their way to help me. Emily Burgoyne was extremely helpful during my brief stint at the Baptist Missionary Archive, Angus Library in Oxford and continued to track down elusive materials even after I had returned to India. Bennie Crockett gave me permission to reproduce images from the William Carey Center, Hattiesburg, Mississippi, USA, and Phaedra Casey at the Brunel University London Archives very graciously allowed me to access research materials pertaining to the British and Foreign School Society. I am equally grateful to the staff of India Office at the British Library in London; the John Rylands Library in Manchester; the Sahitya Akademi, Delhi; the National Archives of India; the Asiatic Society, Calcutta; and Carey Library and Research Centre, Serampore.

Finally, the work was sustained by the help, support and encouragement of my family and friends. My sister Sujata has been the first sounding board for my ideas, and like in every point of my life, has been my best friend and critic. To Ayan and Pinku I am grateful for their patience and understanding, and above all I owe everything to my parents, who would have been very proud had they been here.

The role of the British missionaries has been perhaps the single most important factor related to the long existence of the British in India. The involvement of missionaries in establishing educational institutions and the dissemination of materialist and humanist learning has enabled generations of Indians to have benefited from scholastic intercourse. Missionary activities in a colonial context have time and again been criticized for the ulterior motives of evangelization and conversion. In India, missionaries have been either the target of vitriolic attacks or are regarded as the face of a benevolent imperialism that introduced a modern way of life. It is precisely because of such contrasting reactions that more scholarly insights are required to gauge the importance of missionaries in reforming indigenous lives in India. Of course, evangelization and conversion have remained inextricably entwined to colonization and empire building. At the same time, I can vouch, having studied in a convent school and college (an indigenous lingo for educational institutions run by missionaries) that the overall general feeling towards missionaries is undoubtedly of appreciation for having enriched the intellectual and moral life of Indians.

In spite of their positive input, missionaries remain largely unacknowledged, themselves preferring to remain in the shadows. Missionary activity in India has been one of the largest colonial ventures, but there are very few scholarly writings that throw light on this crucial encounter. Though a lot of writings exist by the missionaries themselves, there is a surprising lack of writings on them. One obvious deterrent to any study on missionaries in India is the sheer size and scope of such studies. My effort has been to limit the study to Bengal. Bengal was the place where at the end of the seventeenth century Job Charnock pitched his tent on a marshy piece of land and made an empire from it. It was again the place where, a century later, William Carey landed with his family, tired and battered after a long journey from England, hoping to establish an evangelical mission. Both men were hugely successful. Evangelization remained an intrinsic part in the establishment of the British Empire in India, and their mutual dependence paved the success of the British existence in India. What remains a disconcerting thought, though, is that apart from a handful of scholars and missiologists, there is a general lack of awareness regarding the involvement of the missionaries in laying the bedrock of the Indian education system. Some of the more prominent names like William Carey, fondly remembered as Carey