First published 2009 by Transaction Publishers

Published 2017 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 2009 by Taylor & Francis.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Library of Congress Catalog Number: 2004041243

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

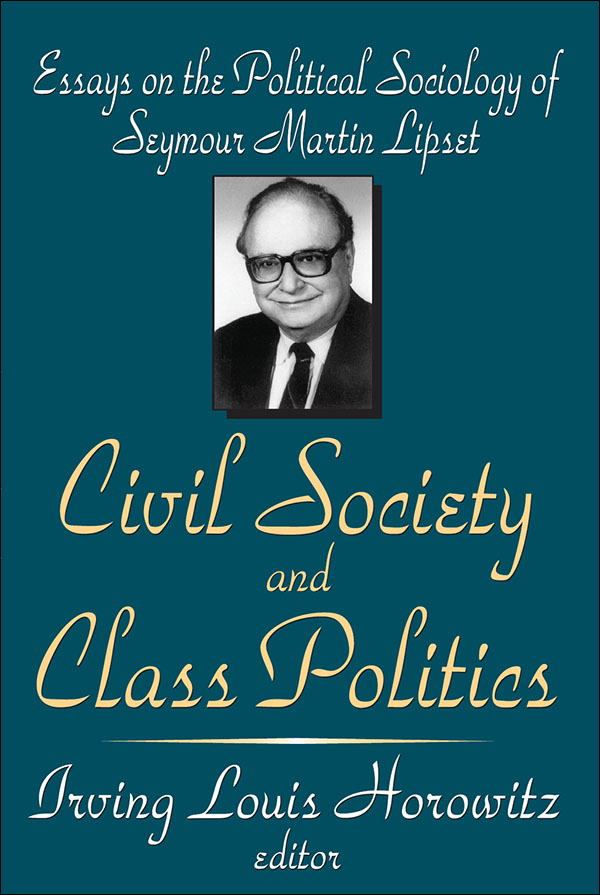

Civil society and class politics : essays on the political sociology of

Seymour Martin Lipset / Irving Louis Horowitz, editor.

p. cm.

Papers originally presented at a series of invited panels at the 2002 meetings of the Eastern Sociological Society

Includes bibliographical references. ISBN: 0-7658-0818-8 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. Lipset, Seymour MartinCongresses. 2. Political sociology Congresses. I. Horowitz, Irving Louis. II. Eastern Sociological Society (U. S.)

JA76.C538 2004

306.2dc22

2004041243

ISBN 13: 978-0-7658-0818-9 (pbk)

A special symposium of this type requires the guidance and assistance of a number of fine people. Such is the case for this tribute to the work and career of Seymour Martin Lipset. To start with, I would like to thank the steady and tireless support of Sydnee Lipset. It is no exaggeration to say that she single-handedly made sure that contributions were received from key participants in the various panels of the Eastern Sociological Society meetings of 2002 at which oral contributions were first presented. No less important were the efforts of Robert Smith to organize the three sessions into coherent and compelling panels. A special thanks is due to Richard Koffler, editorial director of Aldine in the United States, to call attention to the work of Dick Houtman as a statement entirely worthy of inclusion in this special effort. Finally, my appreciation is due to Lawrence Nichols, the editor of The American Sociologist, for both agreeing to and supporting this material to initially appear as a special issue of the journal and for me to serve as its special editor. It goes without saying that each participant in this volume responded to the call for final drafts and editorial refinements in a warm and collegial spirit of doing honor to a beloved colleague.

Irving Louis Horowitz

Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey

July 15, 2003

1

What Happened to Socialism and Does It Matter?

Glazer Nathan

Seymour Martin Lipsets and Gary Marks It Didnt Happen Here: Why Socialism Failed in the United States represents his most recent and most substantial entry in his now fifty-year-old effort to understand why socialism failed in the United States, while it succeeded, in the sense of creating mass parties, with opportunities to govern, in the other major industrial societies and English-speaking democracies. (Since I am discussing this book in the context of a discussion of Lipsets involvement with this problem through his entire professional life, I hope Gary Marks will forgive me if I use the shorthand referring to the book as Lipsets, with the understanding that of course Marks is a full co-author. There is no indication in the book how the responsibility, for research and writing, was divided.) The book conveniently lists all of Lipsets other books, and we can see that from the beginning the failure of socialism has been a central issue, perhaps the central issue, in his intellectual life.

Nathan Glazer is Professor of Education and Sociology, Emeritus, at Harvard University. He is co-editor of the journal The Public Interest and the author most recently of The Limits of Social Policy and We Are All Multiculturists Now.

Thus his first book, Agrarian Socialism, asks, how come a socialist government was able to take power in a Canadian province and by direct implication, how come no socialist party has ever won election to head an American state? (Socialists did govern for a time a few American cities.) His second book, Union Democracy, with Martin Trow and James Coleman, took up a central theme in the problem of the failure of socialismthe difficulty of maintaining democracy in socialist parties and unions against the power of bureaucracy, a theme first raised by Robert Michels. This is an issue that troubled many young socialists of Lipsets generation. And his third, with Reinhard Bendix, Social Mobility in Industrial Society, took up one major thesis in the attempt to explain the failure of socialism in the United States: the argument that because of the greater opportunities for individual social mobility available in the United States, socialismwith its promise of raising the position of the entire working classhad less appeal in the United States than in other industrial democracies.

The comparison with Canada that was initiated in the study of the relative success of socialism in Canada has been pursued in other articles and books, most recently Continental Divide and Distinctive Cultures: Canada and the United States. A major theme in these books is the differences that make Canada more friendly to social democracy and the welfare state, and the United States so antagonistic to them.

We can also see this question, why no socialism in the United States, coming tangentially into other major topics Lipset has addressed in his work. His books on the United Statesfrom The First New Nation to American Exceptionalismconsider one major thesis in the debate on why there is no socialism in the United States, and that is the force and continuity of the distinctive American values of individualism, egalitarianism (of a distinctive and special American cast), and anti-statism. Of course it would be foolish to say the single motivation of Lipsets large oeuvre is plumbing the problem of why the United States never developed a strong socialist party, for there have been other major themes of interest in his workhigher education, student revolt, the sociology of American Jews, and the whole large sweep of issues raised by democracy and the challenges to democracy.

But I am particularly attuned to this central interest of Lipsets because I shared it with him for some years. We met as students at City College, both taking the same route from the East Bronx by elevated line and subway to 137th Street on the West Side of Manhattan. Lipset was a socialist and a member of a socialist youth group. I was also a socialist, though of a different group and somewhat different persuasion. It was not long before the failure of socialismso attractive to so many students of City College, so powerful in the neighborhoods from which we cameto make headway in the United States generally engaged our interest, as we moved through different political orientations.