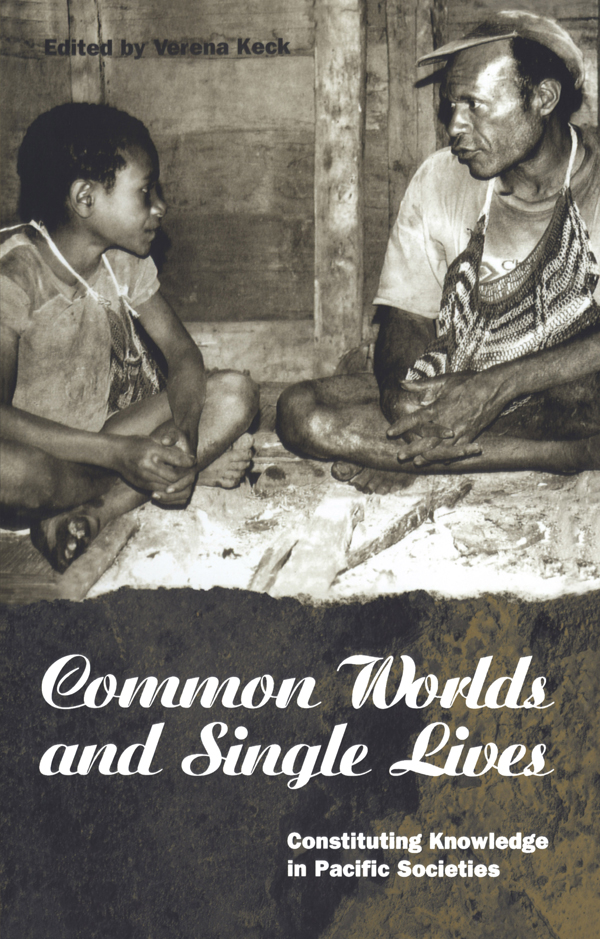

First published in 1998 by Berg Publishers

Published 2020 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

605 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Verena Keck 1998

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the Library of Congress.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Typeset by JS Typesetting, Wellingborough, Northants.

ISBN 13: 978-1-8597-3164-2 (hbk)

ISBN 13: 978-1-8597-3169-7 (pbk)

Verena Keck

In 1988 I visited the Nankina Valley, a remote area in the Finisterre Range in the Madang Province of Papua New Guinea (PNG). I was doing fieldwork among the neighbouring Yupno and I was curious about Nankina culture. When I arrived there, a young man who was full of resentment said in answer to my questions:

We have always been here. Then came the missionaries and threw everything out. They prohibited all the traditional things. And we gave them up. Now you come and ask us about the traditions of our ancestors and we dont know anything anymore. We are totally confused. Is it our fault?

I assume that many anthropologists have had this experience. But I also assume that many anthropologists upon reading these innocuous introductory lines might have an uneasy feeling something isnt quite right here. So I did fieldwork (Keck 1992, 1993, 1994) among the Yupno (in actual fact, the Yupno do not have a name for themselves). After a while, I became curious about the Nankina who live in the neighbouring Nankina Valley. I knew, however, that Nankina just like Yupno was only the name of the respective river, that many Nankina had immigrated into the Yupno Valley by crossing the mountains and that some of them also lived in the towns of Madang and Lae. Nevertheless, for the time being I equated Nankina with the valley of the same name. I then had numerous talks with Nankina informants but only with middle-aged men as they were the only ones to speak Tok Pisin. Yet they readily supplied me with information on kinship structure, settlement patterns, growing things in their gardens, life cycles but still I suspected their single lives to be more varied and more complex; that the young people, the elderly and the women looked upon many things differently from their opinion leaders. In the end, it set me thinking how the young man quoted above talked about traditional things that the Lutheran catechists had prohibited and that could be disposed of like a commodity while, as it seemed to me, in his everyday life he behaved in a most traditional way.

I suppose that in the beginning we all felt something was not right with the description because, at the close of the twentieth century, the traditional concepts of culture, individual and knowledge are simply lost to us and we have at least to question and, depending on the case, to invent them anew.

Deterritorialized Cultures

The idea of culture appears today in an amazingly wide variety of contexts and has experienced a veritable boom since the 1970s, spawning a whole string of new compound words formed with multi-, pluri-, inter-, trans- and culturalism, as well as many different ethno-fashions. The traditional concept of culture is passing through a period of widespread and indiscriminate use in different social spheres. It starts behaving in a global way ubiquitous, encompassing, all-explanatory (M. Strathern 1995: 155). Any people, sect, company, band or maker of brands may draw on culture but, above all wherever people differentiate between people, culture is evidence for diversity. In the course of the shrinking of the world due to globalization (Harvey 1989) and of the increasing movement of people towards common worlds, the concept was appropriated by others and anthropologists lost control over one of their most basic terms (Comaroff and Comaroff 1992). The paradoxical result is that anthropological writings are increasingly being consulted by people wishing to construct cultural identities of a totalizing sort which the anthropologists now find highly problematic. This has to be explained.

Few concepts have been as pervasively effective in anthropology as the often quoted passage from E.B. Tylors Primitive Culture of 1871, which describes culture and civilization as, in the widest sense, a complete whole that includes knowledge, religious beliefs, art, morals, laws and customs; in other words, all the skills and characteristics human beings acquire as members of a society. However, these ideas of homogeneity, coherence and continuity have to be called into question. Wicker (1997) lists two main kinds of disapproval. Critics of the first kind view the classical definition of culture as a continuation of older concepts of race deriving from Herders notion of the Volksgeist. Culture, like race, is perceived as defying definition. This emphasis on the collective we implies the incommensurability of the different cultural forms and renders this view attractive for the political and cultural New Right as well. Critics of the second kind are the ethnicity researchers investigating the ethnic borders themselves and the mechanisms used to preserve them. Ethnic lines of separation were found to constitute and preserve themselves through processes of ascription to self and others. It was not possible, however, to trace the origins of these processes of ethnicity to the different cultural representations of the groups involved (Barth 1969; Glazer and Moynihan 1975).

In the course of the history of anthropology obviously there have also been other attempts to more precisely define the object of research but it seems that the starting point has always been three kinds of emphasis that were believed to fit together and also appear together (Hannerz 1996: 8). One is that culture is learned, acquired in everyday social life, as it were; the software needed for programming the biologically given hardware which, thanks to the cognitive sciences, is becoming increasingly better known. The second emphasis is that culture is something that comes in various packages, distinctive to different human collectivities, and that, as a rule, these collectivities belong to territories. Finally, culture should somehow be integrated, fitting in neatly something equally distributed among all its members.