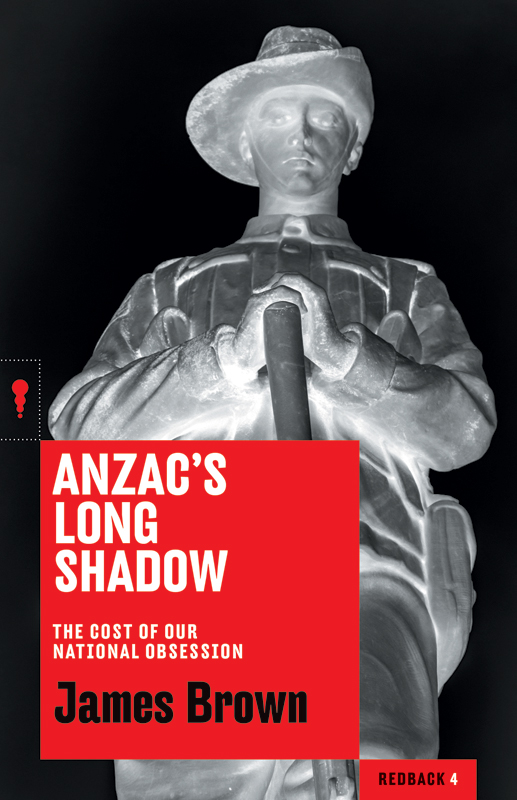

Published by Redback,

an imprint of Schwartz Publishing Pty Ltd

3739 Langridge Street

Collingwood VIC 3066 Australia

email: enquiries@blackincbooks.com

http://www.blackincbooks.com

Copyright James Brown 2014

James Brown asserts the right to be known as the author of this work.

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior consent of the publishers.

The National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry:

Brown, James, author.

Anzacs long shadow : the cost of our national obsession / James Brown.

9781863956390 (paperback)

9781922231352 (ebook)

Australia. Army. Australian and New Zealand Army Corps Influence. Australian Defence Force Management. Memorialization Australia. World War, 1914-1918 Campaigns Turkey Gallipoli Peninsula Influence. Soldiers Care Australia. Veterans Care Australia. Australia History 1914-1918 Influence.

355.60994

PROLOGUE: ON PARADE

These are not people you see face to face very often, hipster artists and soldiers, but here they are in the one room, gazing at Ben Quiltys depictions of Australian soldiers in Afghanistan. The room is packed full of the curious and the thirsty. I ask an acquaintance from the art world whether this is a normal opening-night crowd. At least three times as big as Ive seen here before, he replies.

I recognise a few faces. Soldiers and officers Ive served with. Some whose work I know only by reputation. Public servants whove worked in Afghanistan, public figures, too. Telling the military from the maestros is best done by looking down. Even when out of uniform, the fighting folk are identifiable by their fastidious shoes. Some officers wear their most corporate suits, secretly relishing the opportunity to dress like the rest of societys professionals. One soldier dresses according to the unwritten manual that specifies a dark suit must be worn with a black shirt and garish tie as at a mafia wedding, or mid-western US prom night. A nonchalant few are in uniform. A row of medals occasionally clinks across a breast. Each of the military faces looks excited. This is unfamiliar territory for them, and theyre the stars of the show.

In some ways, Ben Quilty resembles special forces soldiers Ive known slim, bristly and focused. It is clear why he was accepted by these professional warriors and allowed to tell their story. His selection as an official artist for the Australian War Memorial was an unusual move for such a conservative institution, but Quiltys own choice to paint soldiers at war makes a lot of sense his oeuvre depicts plenty of young men making risky decisions. In the military, a sense of professional duty can help stifle recognition that going to a combat zone is not a wise course of action. Yet Quilty made a cold and clear decision to journey to Afghanistan to paint men and women at war no easy choice.

Up close, Quiltys paintings are strong yet discombobulated shards of paint. They make no sense. In the thronging crowd no one can quite get the perspective they need to admire what he has done. So too in war, perspective is elusive. Most Australian soldiers fighting in Afghanistan have such a limited view. A valley here, a village there. Death or worse is close at hand in your face and at your feet. A moments inattention can be your, and your mates, last. The close-up intensity of survival removes the luxury of perspective, the step back to make sense of so much chaos and noise.

In the gallery downstairs, there is more of that elusive perspective. A long, meandering timeline of the Afghan War is strung around the bare white walls, scrawled in plain black texta. I trace time around the room and realise Ive forgotten just how long this war has been raging. Weve been in Afghanistan longer than the Russians. A child born on the eve of the 2001 American invasion might enter high school this year. In front of me I recognise a warrior I know, whose finely tailored suit tapers to conceal two prosthetic legs.

The late critic Robert Hughes once wrote that the purpose of art is to close the gap between you and everything that is not you. To make the world whole and comprehensible, to restore it to us in all its glory and its occasional nastiness.

The gap between our soldiers and the society they serve is a chasm. This year an Anzac festival begins, a commemorative program so extravagant that it would make sultans swoon and pharaohs envious. But commemorating soldiers is not the same as connecting with them.

Anzac has become our longest eulogy, our secular sacred rite, our national story. A day when our myth-making paints glory and honour so thickly on those in the military that it almost suffocates them. The historian Mark McKenna wrote, In little over 50 years, we have so dramatically transformed our conception of what happened at Anzac Cove on 25 April 1915 that the men who clawed their way up those steep hills would not recognise themselves in the images we have created of them. If the original Anzacs cannot find themselves in Anzac Day, then what hope have our returning Afghan veterans?

Anzac Day has morphed into a sort of military Halloween. We have Disneyfied the terrors of war like so many ghosts and goblins. It has become a day when some dress up in whatever military costume might be handy. Where military re-enactors enjoy the same status as military veterans. The descendants of citizen soldiers swell the ranks of parades their grandfathers might have avoided, claiming their share of the glory and worship, swimming in a sea of nostalgia. Sort through all this and youll find the servicemen and women increasingly standing to one side. Those who have fought fiercest in Uruzgans narrow green valleys and on its vast brown hills forgo their uniforms more often than not. They dont want honour that rides with hubris. Or glory bestowed by a society that fetishises war but doesnt know the first damn thing about fighting it. A surfeit of honour can scar todays returning soldiers as much as insults scarred our Vietnam veterans.

Months after he returned from Afghanistan, a senior army officer told me that his soldiers were coming back ashamed that they had not measured up to the heroic giants of Anzac. Unlike in the past, victory in our recent wars has been marked more often by an absence of violence than furious personal feats of it. Our Anzac narrative doesnt yet have a place for quiet professional soldiers doing their job for those whose families cant understand what they actually did in Afghanistan, despite the number of war films theyve watched and odes theyve recited.