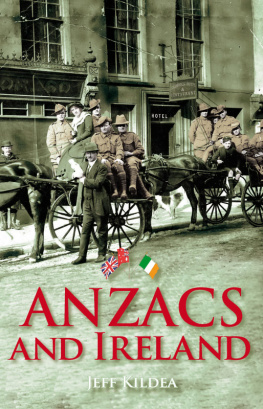

ANZACS

AND IRELAND

JEFF KILDEA is a barrister in Sydney with a PhD in history from the University of New South Wales, where he has lectured in Irish Studies. He is the author of Tearing the Fabric: Sectarianism in Australia 19101925 and has written articles and given papers on the Irish in early twentieth-century Australia.

a splendid and supremely useful, as well as a consistently interesting record of an aspect of the Great War, and of unexpected IrishAustralian connections. Without it we would be much the poorer. Tom Keneally

The people of Australia and Ireland have much in common based on genealogy and a shared heritage. The connections between Anzacs and the Irish in World War I have been little known until now. Jeff Kildea tells the story of how those connections were forged. Australian and Irish soldiers fought alongside each other at Gallipoli, the Western Front and in Palestine, and thousands of Irish-born men and women enlisted in the Australian forces. But it was in Ireland itself that Australian soldiers cemented their relationships with Ireland and its people, as tourists on leave, in some cases becoming involved in the Easter Rising of 1916, while some failed to return and are buried in Irish soil.

ANZACS

AND IRELAND

JEFF KILDEA

A UNSW Press book

Published by

University of New South Wales Press Ltd

University of New South Wales

Sydney NSW 2052

AUSTRALIA

www.unswpress.com.au

Jeff Kildea 2007

First published 2007

This book is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced by any process without written permission. Inquiries should be addressed to the publisher.

National Library of Australia

Cataloguing-in-Publication entry

Kildea, Jeff.

Anzacs and Ireland.

Bibliography.

Includes index.

ISBN 978 0 86840 877 4.

1. Australia. Army. Australian and New Zealand Army Corps. 2. World War, 1914-1918 - Australia. 3. World War, 1914-1918 - Ireland. 4. Irish Australian soldiers - History. 5. Ireland - Social conditions. I. Title.

940.30891620994

Design Joshua Leuii

Cover Off to the lakes, Corporal James Nelson next to his bride Joy on a jaunting cart in Killarney (Photo courtesy of John Gallagher). During the First World War the red ensign was widely associated with Australian soldiers, while the Irish tricolour, adopted as the national flag in 1922, symbolised Irish nationalism, particularly after the 1916 Easter Rising.

CONTENTS

Gallipoli

Australian soldiers and the Easter Rising of 1916

Irish men and women in the Australian forces

Australian soldiers on leave in Ireland

Australian war graves in Ireland

Remembrance in Australia and Ireland

FOREWORD

Some years past I met Jeff Kildea at a conference at the University of New South Wales. I became aware that this personable fellow was a lawyer amongst historians, as I was a novelist amongst historians. But he was also a historian amongst historians, and this book proves that.

When Australians speak of Gallipoli, they think of two colonial peoples, the Australians and New Zealanders, rising from the trenches to show the Old World their fibre. But Kildea reminds us of a longcolonised people, the Irish, who were also there to prove something. If they were nationalists, they hoped to prove that their loyalty deserved home rule. If they were loyalists, they wanted to prove that they were Britons par excellence, and must not be sold out to the Sinn Finers. The same Turkish artillery that cut its awful swathes in the Australians and New Zealanders, also indiscriminately and without prejudice ended Irish lives, Green and Orange, in regiments that fought beside the Anzacs on that terrible peninsula.

This is where Jeff Kildea begins his tale, in the Dardanelles where Australians, many of them of Celtic derivation, were brothers-in-arms to the Irish. But that was but the beginning of the association. When the Australian survivors of Gallipoli, including Private Chapman who had landed in the first wave, reached Britain after the evacuation of Gallipoli, many were inevitably drawn to Ireland as springtime came to Europe. But 1916 was a time of great nationalist and republican unrest, and the part of the Anzacs in all that has never been systematically researched or related.

On the eve of the first anniversary of Gallipoli, the Irish rebels rose in Dublin. Expert Anzac snipers, recalled to arms from their leave, directed accurate fire on rebels from the roof of Trinity College. Despite antipodean rebel traditions, they were not tempted to side with the rebels, Pearse, de Valera and Connolly, any more than were most Dubliners at that time it would be later, through the folly of British reprisals and the poetry of Yeats, that the Easter Rising would take on its terrible beauty. The above-mentioned Private Chapman fought in the south-west sector of the city and nonchalantly accepted rifle and ammunition and nearly got hit several times. Others were also caught up in one of the Empires last Irish gasps. But the defeat of the rebels was inevitable and it was Australian arms, amongst others, who guarded the rebels at Arbour Hill. Eyewitness accounts of the brutal behaviour of some Crown troops were published in Australian newspapers, and the severity with which the British treated many of the rebels would shock much Australian opinion, and have an influence on the peace movement and the two failed conscription referenda Billy Hughes introduced in 1916 and 1917.

And what was the reaction of the almost seven thousand Irish-born who served in the Australian forces, let alone that of the far more numerous first-generation Australians whose parents were Irish? Did any Australian soldiers, of whatever background, toy with the idea of deserting, or even actually desert in Ireland? And did Australians on leave experience the increasing hostility of the Irish, as lines between nationalists and the rest hardened. And in the end, when the war was over, how did Australia remember the dead? And how did Ireland, where the question was: which dead?

One last question: are you fascinated yet? By the connections, the ironies, the unpredictabilities of these issues? The most useful history expands the equation we believe we already understand. We think we know about Ireland and Australia, and our own uneasy brands of republicanism and loyalism. But with its rich research, this book helps break that accepted mould. In doing so, it excites and stimulates our imagination, and may even change the way historians deal with a given question in the future.

Tom Keneally

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I am grateful to the many people who have assisted me in the research and writing of this book, including Seamus Breslin, Philip Lecane, Jill Mabbott, Paul Maguire, Paudie McGrath, Oliver Murphy, Joe OLoughlin, Anne Stevens, Robert Thompson and Peter Threlfall, who have given me the benefit of their research; Christine Armstrong, Yvonne Bell, John Gallagher, Jane Keneally, Barrie Kinchington, Christy Mannix, Bill McHugh, Margaret McKenna, Phill McKenna, Frank Quinane and Terry Quinane, who have provided information on their relatives; Geoff Barr, Steven Becker, Paul Brennan, John Connor, Peter Dennis, Bill Gammage, Keith Jeffery, Michael Kildea, Jenny Macleod, Michael McKernan, Cheryl Mongan, Peter Moore, the late Patrick OFarrell and Richard Reid, who have read chapters or provided leads; Gordon Bickley and Rosemary Kildea, who have assisted with the research; Geoff Graham, who helped me find the graves; and the staff at the Australian War Memorial, the National Archives of Australia, the National Archives (UK), the National Archives of Ireland, the National Library of Ireland, the Irish Military Archives, Trinity College Manuscripts Department and the Mitchell was carried out with assistance from the Army History Research Grants Scheme. I would especially like to thank my wife Robyn and our children, who have put up with me for the many years during which I have wrestled with this project.

Next page