Praise for Helen Litton:

This autobiography, edited with great skill by Helen Litton, is particularly valuable as it casts a fresh perspective on key figures and moments in the struggle for independence. The Irish Catholic on Kathleen Clarke: Revolutionary Woman

[A]n uncomplicated biography of the minence grise of the Rising. Sunday Business Post on Thomas Clarke: 16 Lives

As a short intelligent overview of 184550, it will be hard to surpass. RT Guide on The Irish Famine: An Illustrated History

From the time that Britain first began to take an interest in the country on her western flank in the twelfth century, the history of the two islands was one of constant struggle. The most important developments are often those that take place slowly and quietly, taking years to mature, but these possibilities of forward movement can be side-tracked or derailed completely by sudden eruptions of violence. Sometimes these eruptions help to encourage something which might otherwise not have happened.

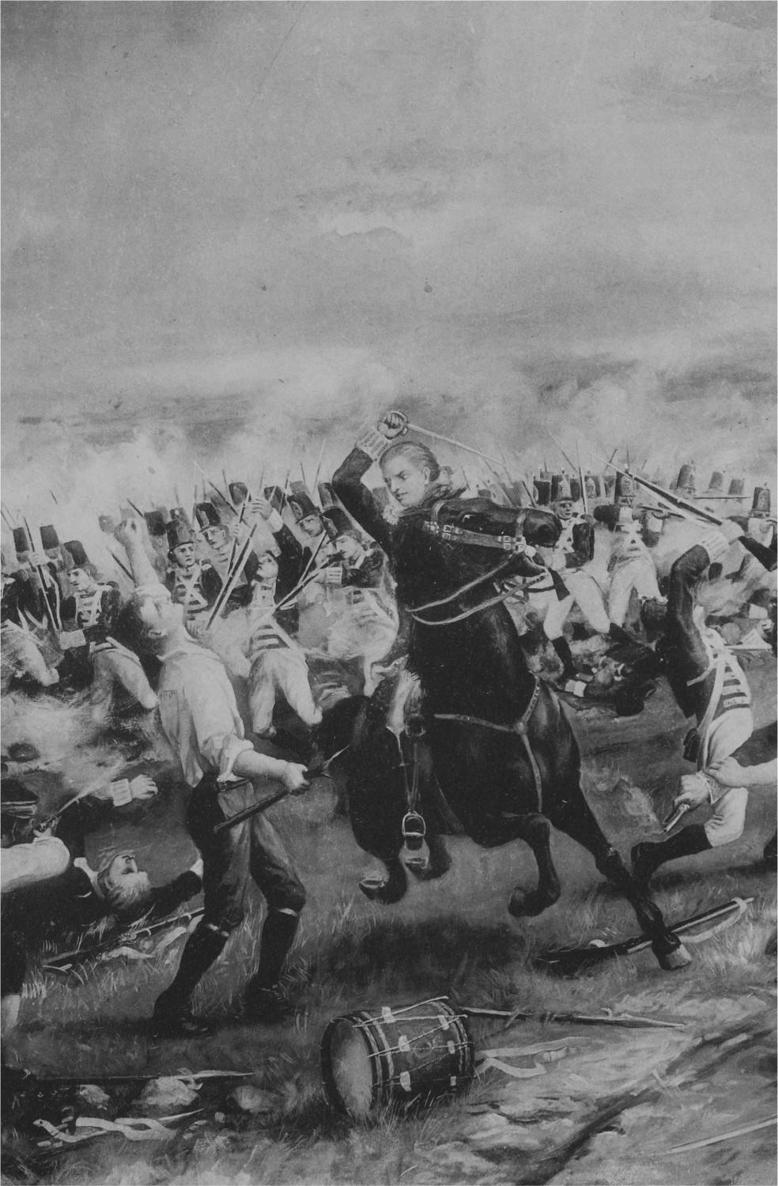

The 1798 Rebellion, and those following it, were manifestations of a groundswell of movement for civil and religious rights, and national independence, in a way not true of earlier uprisings. The seventeenth-century Nine Years War, for example, spearheaded by Hugh ONeill, earl of Tyrone and Rory ODonnell, earl of Tyrconnell, was a final, despairing effort to hold onto ancestral lands, and prevent the inexorable movement of Tudor power throughout Ireland. The war ended when the chiefs of Ireland sailed away to Spain in September 1607, an event known as The Flight of the Earls. They left their people behind in a war-ravaged countryside, facing starvation and brutality. It is unlikely that these leaders were thinking in nationalistic terms; nationalism, as such, was a development of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Each chief was fighting for his own heritage, and to hold on to the old Gaelic traditions.

The Tudor system of plantations, i.e., planting Protestant settlers from Britain in confiscated lands in Ireland, continued through the seventeenth century. Any whiff of rebellion merely provided the authorities with further excuses to confiscate land, a sort of fig-leaf to conceal greed. The tensions caused by placing small, vulnerable groups of foreign settlers among large numbers of resentful, disaffected natives often led to brutal and despairing outbreaks, instantly punished by the arrival of troops.

One of these was the 1641 Rebellion, planned in Ulster by members of the dispossessed noble Gaelic families. Rebels plundered Dundalk, Newry, Carrickmacross and other towns. Many settler families were killed or injured, and rumours of mass slaughters terrified the planters. The rising spread to Connacht and Leinster, and as far as Limerick and Tipperary, but by spring of 1642, it had been defeated. The Confederate War which followed lasted until 1644. The uprising rooted itself in Protestant mythology as an example of what Irish Catholics were capable of if they were not strictly controlled, or, preferably, exterminated. But there had been very little in the way of central co-ordination or national aim to begin with.

This book may help to demonstrate how successful later leaders actually were, either in imposing any kind of central command, or in developing a universally supported aim through their activities.

I am exceedingly grateful to The OBrien Press for allowing me to make some additions to the original text, including the new chapter on the War of Independence, and for their assistance in choosing illustrations.

The train of explosive which led to rebellion in 1798 was laid by the American War of Independence (177583), and the fuse was lit by the French Revolution of 1789. Eighteenth-century Western Europe was a ferment of new ideas about the Rights of Man, democracy and republicanism, and a growing resentment of tyranny and royalism.

In Ireland, these ideas were slow to take root, largely because there was no system of universal education. Those who were first attracted by them were educated middle-class gentlemen, including some members of the Irish Parliament, based in Dublin. Many of those involved in the United Irish movement, which instigated the rebellion, were Presbyterians, belonging to a form of Protestantism which differed from the dominant Church of Ireland. Presbyterians had suffered along with Roman Catholics under a range of Penal Laws, which discriminated against those who were not Church of Ireland adherents.

In 1793, a Catholic Relief Act gave Catholics some legal freedoms, but not enough. New thinking about the equality of all humankind in the sight of God, and the offensiveness of bigotry and prejudice on the grounds of religion, inspired the leaders of the 1798 Rebellion to work for a freer and more equal society. This would mean removing the monarch as the head of state, and they accepted that this could be done only by force.

R OOTS OF THE U NITED I RISHMEN

The Volunteers, a peoples militia, had been formed in Ireland in 1778 to defend the country against possible invasion by France, while Britain was embroiled in the American War of Independence. The Volunteers gradually developed in a political direction, and supported the principle that the Irish Parliament should be fully independent of the British Parliament at Westminster. At that time, laws passed in the Irish Parliament had to be ratified in Westminster, and could be overturned there too. Some Irish MPs were growing impatient at this lack of autonomy, but others were looking for even closer links with Britain, with one parliament for both countries.

In Dungannon, County Tyrone, a huge Volunteer Convention was held in 1782; by then, the Volunteers numbered about 80,000. This movement placed intense pressure on the British government, and the Irish Parliament was allowed to pass a Declaration of Independence. This gave it a larger degree of executive function, but it was still executively dependent on Britain, and any sense of freedom was more apparent than real. It was known as Grattans Parliament after its most prominent and charismatic member, Henry Grattan, and it lasted until 1800, when an Act of Union between Britain and Ireland swept it away completely.

Henry Grattan (17461820) was educated at Trinity College, Dublin, and was called to the Bar in 1772, became an MP in the Irish Parliament in 1775, and was prominent in calling for its independence from the British Parliament. When this was achieved in 1782, it became known as Grattans Parliament, although he refused to hold any office. A noted orator, he campaigned for Catholic Emancipation, and later strongly opposed the Act of Union (1800) under which the parliaments were reunited.

In 1782, a Relief Act gave Catholics full rights to own land and property, and the need for resistance to British rule seemed even less urgent. The Volunteer companies gradually disbanded, unwilling to take the final step of physically attacking the institutions of the state, but a remnant formed a secret radical committee in Belfast, to win support for revolutionary ideas. These radicals were brought together by their admiration for a pamphlet called An Argument on Behalf of the Catholics of Ireland. The anonymous author called for Protestant and Catholic to join together in mutual respect and esteem, to fight for Irish independence. Samuel Neilson, a leader of the Belfast committee, contacted the author of the pamphlet through Thomas Russell, another radical, and found him to be a young Protestant called Theobald Wolfe Tone.