Five Irish women

The second republic, 19602016

EMER NOLAN

Manchester University Press

Copyright Emer Nolan 2019

The right of Emer Nolan to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Published by Manchester University Press

Altrincham Street, Manchester M1 7JA

www.manchesteruniversitypress.co.uk

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 978 1 5261 3674 9 hardback

First published 2019

The publisher has no responsibility for the persistence or accuracy of URLs for any external or third-party internet websites referred to in this book, and does not guarantee that any content on such websites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate.

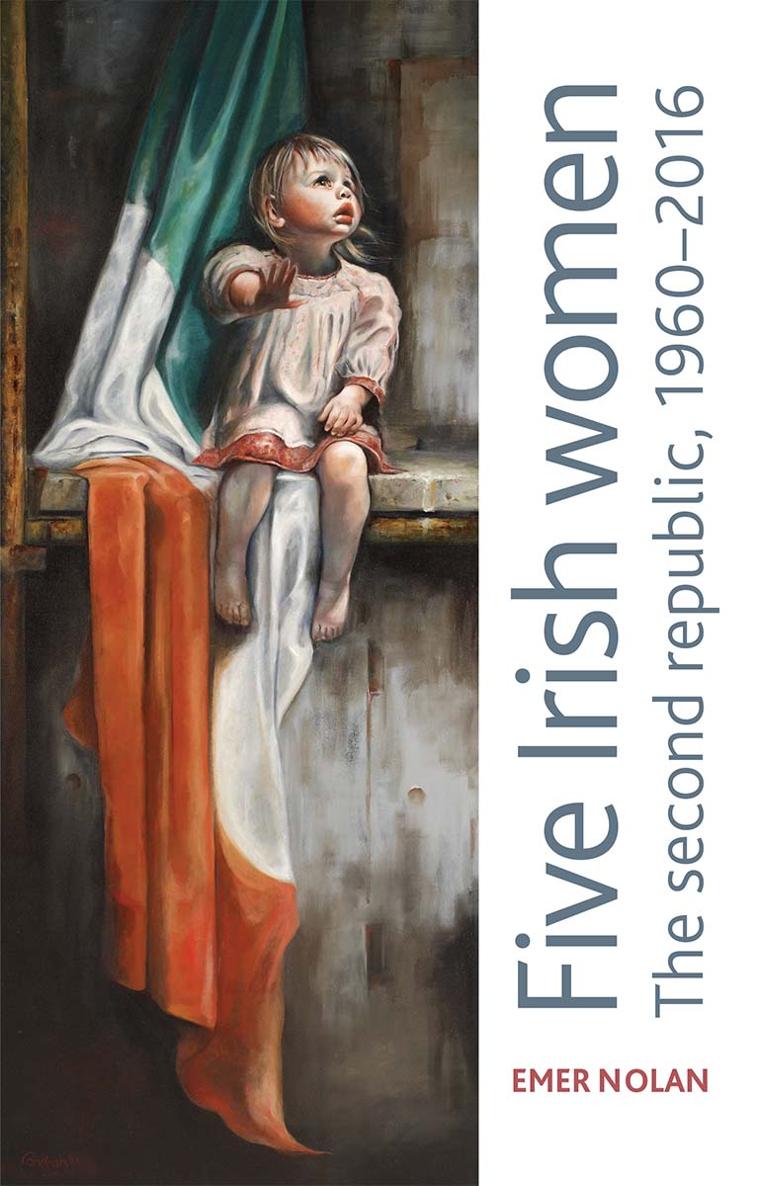

Cover image: upon small shoulders by Neil Condron. Oil on canvas (7 by 3)

Typeset in Sabon by

Servis Filmsetting Ltd, Stockport, Cheshire

For Iseult Deane

Contents

I am grateful to Maynooth University for the award of a period of sabbatical leave during which this book was drafted. My thanks to the Head of the English Department at Maynooth, Colin Graham, to my departmental colleagues, and particularly to Amanda Bent and Tracy OFlaherty for their kind assistance during my term as Head of the School of English, Theatre and Media Studies. It has been an education in itself to work with the research students, past and present, in Irish and twentieth-century literature at Maynooth, especially Thomas Connolly, Daniel Curran, Bridget English, Matthew Fogarty, Francis Lomax and Eoghan Smith. The staff at the University Library at Maynooth and at the National Library of Ireland have been unfailingly helpful. An earlier version of Chapter 2 appeared in Field Day Review 6 (2010). It profited from the skilful editing of Ciaran Deane of Field Day Publications, who also advised on the illustrations for this volume. Lelia Doolan lent me a copy of her remarkable film, Bernadette: notes on a political journey (Digital Quilts, 2011). I am grateful for the critical engagement of many colleagues and friends in the field of Irish Studies and beyond, including Richard Bourke, Seamus Deane, Jo George, Luke Gibbons, Declan Kiberd, Liam Lanigan, David Lloyd, Breandn Mac Suibhne, Michael McAteer, Conor McCarthy, Barry McCrea, Denise Meagher, Chris Morash, Catherine Morris, Rachel Potter and Kevin Whelan. Joe Cleary, Michael G. Cronin and Sinad Kennedy all found time to read drafts and gave excellent advice. Warm personal thanks are due to my mother, Eileen, and my brothers Lorcan, John, Victor and Peter Nolan. Orla Nolan was enthusiastic about this project at an important moment. The book is dedicated to my wonderful daughter, Iseult Deane, with love.

Matthew Frost, Commissioning Editor at Manchester University Press, oversaw the process of publication with care and patience. My gratitude to him, to my anonymous reviewers, and to all at the press for their hard work in bringing this book into the light of day.

This book is comprised of five portraits of Irish women from various fields literature, journalism, music and politics who have achieved outstanding reputations since around 1960: Edna OBrien, Sinad OConnor, Bernadette McAliskey, Nuala OFaolain and Anne Enright. This is not offered as a representative sample of accomplished Irish women but neither is it a merely random selection. For they are, all of them, quite exceptional in their achievements: all are or have been famous abroad as well as in Ireland, and several could claim at some point of their lives to have been among the most recognisable Irish people in the world. It is quite a homogeneous group in sociological terms: one McAliskey is from a working-class Northern Irish Catholic background, but the others all come from the southern Irish Catholic middle class. However, this book does not aim to be a comprehensive record of the successes of modern Irish women or Irish feminism. Numerous, diverse Irish women have had remarkable careers, sometimes in even more heavily male-dominated realms; there are many other extraordinary women, including important feminist campaigners, who may not have attracted the same level of international media attention as the women considered here. Rather, my focus is on the ways in which these particular distinguished women make sense of their formative experiences as Irish people and how they in turn have been understood as vibrant figures in whom certain liberating aspects of modernity in Ireland have been realised. Their creative work and their broader careers raise particularly compelling questions about womens emancipation, the legacies of modern Irish history and the possibility of radical social transformation in contemporary society. In my view, these are among the most important themes in academic and public debate in Ireland over the last sixty years or so.

In her classic work of 1949, Simone de Beauvoir described women as members of the second sex. While there is no perceived contradiction between a mans humanity and his masculine identity, women have been defined as the other of men that is, they have usually been regarded as human beings of a different and secondary order. In philosophical terms, Beauvoir described women as confined to immanence: close to nature, passive, responsible for the reproduction of people and culture. Men (or at least privileged men) could far more easily aspire to transcendence and to becoming creative innovators. A woman interested in the arts or science or politics was obliged to confront all kinds of preconceptions about her capacities, often including her own internalised ideas about feminine identity. Perceived primarily as a woman, rather than as a person who happens to be female, she was burdened with always having to think about her femininity. Beauvoir wrote that it is very seldom that woman fully assumes the anguished tte--tte with the given world;

Beauvoirs The second sex has been much discussed and sometimes criticised by feminists in succeeding decades, especially since the emergence of the second wave womens movement at the end of the 1960s. To some, her analysis seemed too dismissive of certain traditional dimensions of womens lives, such as motherhood. Further, in holding women to standards of universal achievement that are in practice defined by men, Beauvoir could herself be accused of being masculinist in her values. She is certainly no separatist and she does not regard women as fundamentally different (or superior) to men. But despite all the inevitable disputes about Beauvoirs legacy, some feminist theorists including Toril Moi argue for the continuing importance of Beauvoirs theory of womens freedom for feminism today. As Moi suggests, every woman has the right to speak about her experiences as a woman: it is oppressive to reduce women to their humanity in a way that takes no account of their female bodies or their social experiences. But by the same token, feminism

does not have to be committed to the belief that sex and/or gender differences always manifest themselves in all cultural and personal activities, or that whenever they do, then they are always the most important features of a person or a practice. Womens bodies are human as well as female. Women have interests, capacities, and ambitions that reach far beyond the realm of sexual differences, however one defines these.