OURSELVES ALONE

OURSELVES ALONE

Womens Emigration from Ireland 1885-1920

JANET A. NOLAN

Copyright 1989 by The University Press of Kentucky Paperback edition 2009

The University Press of Kentucky

Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth,

serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre

College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University,

The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College,

Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University,

Morehead State University, Murray State University,

Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University,

University of Kentucky, University of Louisville,

and Western Kentucky University.

All rights reserved.

Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky

663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008

www.kentuckypress.com

The Library of Congress has cataloged the hardcover edition as follows:

Nolan, Janet.

Ourselves alone : womens emigration from Ireland, 18851920 / Janet A. Nolan.

p. cm.

Bibliography: p.

Includes index.

ISBN 0-8131-1684-8 (alk. paper)

1. Young womenIrelandSocial conditions. 2. Single womenIrelandSocial conditions. 3. IrelandEmigration and immigrationHistory. 4. Women immigrantsUnited StatesHistory. 5. IrishUnited StatesHistory. I. Title. II. Title: Womens emigration from Ireland, 18851920.

HQ1600.3.N65 1989 89-35145

304.8'3730415dc20 CIP

ISBN 978-0-8131-9251-2 (alk. paper)

This book is printed on acid-free recycled paper meeting

the requirements of the American National Standard

for Permanence in Paper for Printed Library Materials.

Manufactured in the United States of America.

Member of the Association of American University Presses

To my grandmother,

Mary Ann Donovan Nolan and her son,

William Francis NolanContents

Acknowledgments

My greatest debt is to my teacher and advisor, Professor Emeritus Emiliana P. Noether of the University of Connecticut. Without her encouragement and expertise, this work might never have been completed. Warm thanks are also due to Professors Bruce M. Stave and Irene Q. Brown of the University of Connecticut, Gary Thurston of the University of Rhode Island, and Larry McCaffrey of Loyola University of Chicago for their thoughtful reading and substantive comments.

The completion of this study was also made possible by the generous financial support of both the University of Connecticuts Research Foundation and Loyola University of Chicagos Faculty Development Stipend. In addition, I owe special thanks to Robert Vrecenak and his staff in the Interlibrary Loan Department at the University of Connecticut, Richard Coughlin of the ONeill Library at Boston College, and the staffs of the National Library of Ireland in Dublin, the Newberry Library in Chicago, and the Cudahy Library at Loyola University of Chicago. Professor Ruth-Ann Harris of Northeastern University has also been more than generous in sharing with me the fruits of her imaginative and productive scholarship.

I wish to express my appreciation and thanks to my friends and family, including my aunt Helen and cousin John Donovan, who lent me their memories, and my aunt-by-marriage Margaret Nolan, who, like her mother-in-law Mary Ann Donovan, left Ireland alone. My gratitude also extends to Susan Rogers and Sylvia Rdzak for their patience and good humor during the several typings of this manuscript, and to Professor Lew Erenberg of Loyola University of Chicago for freeing me forever from the tyranny of correction fluid.

Although all these teachers, family, and friends have helped me hone my ideas over the evolution of this work, I take full responsibility for its content, as well as for any errors it might contain.

Chicago, 1989

OURSELVES ALONE

Introduction:

Going Alone

In early April 1888, sixteen-year-old Mary Ann Donovan stood alone on the quays of Queenstown in County Cork waiting to board a ship bound for Boston in far-off America. Her parents had died a few months before, making Mary Ann and her brother John the only members of the family remaining in Ireland. Older sister Ellen had already gone to America. Her letters home were bright spots in the Donovan household in Skibbereen and were eagerly read when the man with the letters from Bandon made his weekly trip to the town. After their parents deaths, Ellen sent the passage money so that her sister could join her.

Mary Ann looked about her. From where she stood, she could read the name, S. S. Marathon, in foot-high letters that stretched along the bow of the ship that would be her home as she crossed the water. It had been a two-day trip from Skibbereen to Queenstown and the ship. Brother John had driven her by cart to Bandon. From there, she had boarded a train to Cork city and, eventually, to the port. John stayed behind. He planned to sell the family farm, and then he too would join his sisters.

As the restraining ropes were lowered, the crowd on the docks surged forward, pushing Mary Ann toward America, along with thousands of other young farm girls like her, toward a better life in a new land.

This was to be the last voyage of the Marathon. After a troubled crossing, the vessel broke down in a northeast gale, one days journey out of Boston Harbor. Towed to the city, never to sail again, the ship carried Mary Ann to America nonetheless.

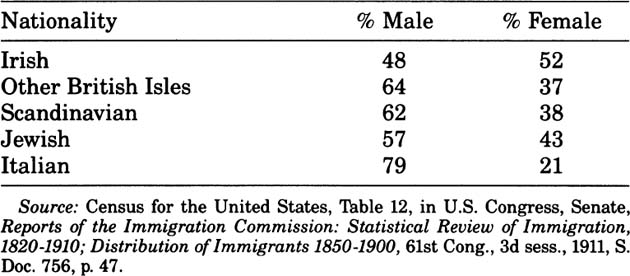

Table 1. Percentage by Sex among Immigrants to the United States, Selected National Groups, 1899-1910

In her adopted land she married and gave birth to nine children, one of whom became my father.

Mary Ann Donovan was one of almost 700,000 young, usually unmarried women, traveling alone, who composed most of the emigrants leaving Ireland between 1885 and 1920. whereas single women dominated Irish emigration for thirty-five years. By the first decade of the twentieth century, the female majority among Irish emigrants was unique among Europeans once again, as can be seen in table 1, which gives immigration totals for the United States, the most popular immigrant destination in the late nineteenth and the early twentieth centuries.

The women who left Ireland during this period did so because they had grown ever more superfluous in their home communities as new demographic and economic patterns transformed Irish life in the half-century before 1880. These changes had lessened these womens chances for becoming wives and thereby attaining adult social and economic status. Since no corresponding expansion of new biological, economic, or social opportunities for unmarried women had taken place, the position of women deteriorated despite a rise in overall economic prosperity. Rather than accept their newly marginal lives as celibate dependents on family farms, however, more and more women left Ireland. By the 1880s their emigration reached epidemic-like proportions, especially in the west and the southwest, the regions undergoing the most abrupt changes in population and economic organization. In view of Irish womens increasingly restricted lives, their decision to emigrate becomes a remarkable example of female self-determination.

Member of the Association of American University Presses

Member of the Association of American University Presses