Published by Abacus

ISBN: 978-0-349-14195-4

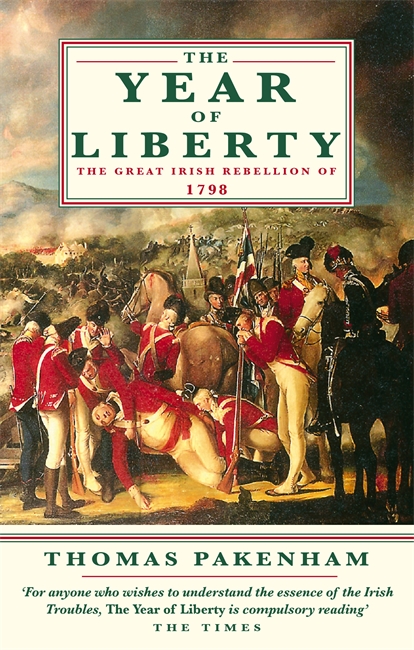

Copyright 1969, 1997 Thomas Pakenham

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

Abacus

Little, Brown Book Group

Carmelite House

50 Victoria Embankment

London EC4Y 0DZ

www.littlebrown.co.uk

www.hachette.co.uk

Thomas Pakenham is the author of The Mountains of Rasselas and The Boer War, which is published in paperback by Abacus. The Scramble for Africa: 18761912 also published by Abacus won the WH Smith Literary Award and the Alan Paton Award. He divides his time between a terraced house in North Kensington, London and a crumbling castle in Ireland. He is married to the writer Valerie Pakenham and they have four children.

For Val as always and in memory of three

friends who inspired this book: John Vaizey,

Angus MacIntyre and Karl Leyser.

Army, Irish Technically, the army of the establishment in Ireland, paid for by the Irish taxpayer. Regulars, militia, fencibles and yeomanry controlled (in theory) by the Irish Commander-in-Chief who was appointed by the British Government.

Cabinet, Irish Informal group of advisers for the Viceroy, including the Lord Chancellor, Speaker, etc.

Chief Secretary Viceroys deputy, who managed government business in Irish House of Commons.

Croppy Name for United Irishman, derived from revolutionary style of close-cropped hair.

Curricle gun Light, mobile artillery piece.

Catholic emancipation As Catholic tenants now had the vote, emancipation largely meant giving Catholic landlords the right to sit in the unreformed Irish Parliament.

Defenders Movement of Catholic peasantry involved in land war against landlords and magistrates. Originated in Ulster to defend Catholic tenants against Protestant Peep-o-Day Boys, forerunners of Orangemen.

Directory, Irish Provincial Formed by United Irish delegates (colonels) from each county in the province, reporting to the shadowy Supreme Executive in Dublin.

Dissenters Nonconformists, mainly Presbyterian, who formed bulk of United Irishmen in Ulster.

Executive, Supreme Directed the United Irish movement from Dublin. Equivalent to the French national Directory.

Fencibles Regiments raised, mainly in Scotland, during the war to supplement regulars. Some served in Ireland.

Lord Lieutenant (see Viceroy).

Militia, Irish 38 regiments and battalions first raised in 1793 to supplement regulars, mainly in 32 Irish counties, partly by using volunteers, partly by ballot. Except in some Ulster counties, most of the rank and file recruited were Catholic, most of the officers Protestant, reflecting class and religious structure of their counties.

Middlemen Farm tenants, mainly Catholic, who exploited long leases and rising rents by sub-letting to small farmers at increasing profit.

Parliament, Irish House of Lords and House of Commons in Dublin, parodying London model. Majority of the 300 seats in the Commons were in closed (rotten) boroughs controlled by great Protestant county families. Catholic peasantry, newly enfranchised in 1793, could only vote for the 64 open seats in the counties.

Speaker, Irish Traditionally adopted more active role than English counterpart as spokesman of Commons.

Tithes Dues payable to local clergy of Established church by tenants irrespective of their own religion.

United Irishmen Founded in 1791 by Protestant radicals claiming they planned to unite Catholics and Protestants in pressing for Catholic emancipation and Parliamentary reform. By mid-1790s a revolutionary movement plotting to set up an independent republic in Ireland, assisted by France.

Viceroy Kings representative in Ireland chosen by the British Prime Minister to be head of the Irish government.

Volunteers Part-time corps, dominated by Protestant gentry but also attracting Ulster radicals, to protect Ireland during war with France and America. Forced government to make political and commercial concessions to Irish Parliament. Suppressed in 1794.

Yeomanry Part-time corps, partly modelled on volunteers, to act as local defence force during war. Raised by individual gentry, it included many Catholic tenants; some had secretly joined the United movement.

Who fears to speak of Ninety-Eight?

Who blushes at the name?

When cowards mock the patriots fate,

Who hangs his head for shame?

The Memory of the Dead

T HE REBELLION of 1798 is the most violent and tragic event in Irish history between the Jacobite wars and the Great Famine.

In the space of a few weeks, 30,000 peoplepeasants armed with pikes and pitch forks, defenceless women and childrenwere cut down or shot or blown like chaff as they charged up to the mouth of the cannon.

The result of the rebellion was no less disastrous: Britain imposed a Union on terms that proved unacceptable to the majority of the Irish people, and there was a legacy of violence and hatred that has persisted to the present day.

How did this catastrophe occur?

The story must be seen in the context of the war between Britain and France and the wave of Jacobin revolutions, impelled by France, that swept through Europe at that time. It is in this contextof ideological war to the deaththat Britain and her Irish Allies were fighting in Ireland. A successful revolution in Ireland, and then Britain would be the next to go.

But there are other themes that need to be stressed, as they have tended to become obscured by later Irish history.

The rebellion was not provoked by Pitt and the British government, as most Irishmen came to believe, in order to pass the Union. On the contrary, it was the result of Pitts failure to have any policy for Ireland. Pitt recognised that all was not well. The Irish Catholic peasantry were some of the most wretched in Europe. The country was governed by a grotesque colonial partnership: a weak British viceroy with British staff, bullied by a narrow oligarchy of Irish Protestants of British settler stock. Pitt could have corrected the abuses of power that had brought the country to the brink of revolution. Distracted by the war with France, he hoped for the best. Ireland was left to its fate.

Equally misplaced was the optimism of Wolfe Tone and the Irish revolutionariesthe United Irishmen. Tone recognised that there could be a terrible irony in that name. Himself of Protestant stock, he knew that the Irish ruling class would be no friends to the revolution. He pinned his hopes on the have-nots: the Presbyterian businessmen and artisans, and the Catholics. With French help, he planned a war of independencea fair and open war as he called it. In fact the rebellion turned out to be a ferocious civil warIrish loyalists against Irish rebelswith many of Tones closest friends committed to the loyalist side.

Most tragic of all were the illusions of the Irish peasantry, intoxicated by the fumes of the French revolution and the heady doctrines of Tom Paines Rights of Man. They were all for Liberty if it meant the end of tithes and taxes and an oppressive government. They were quite unprepared for war.