History of Ireland and the Irish Diaspora

SERIES EDITORS

James S. Donnelly, Jr.

Thomas Archdeacon

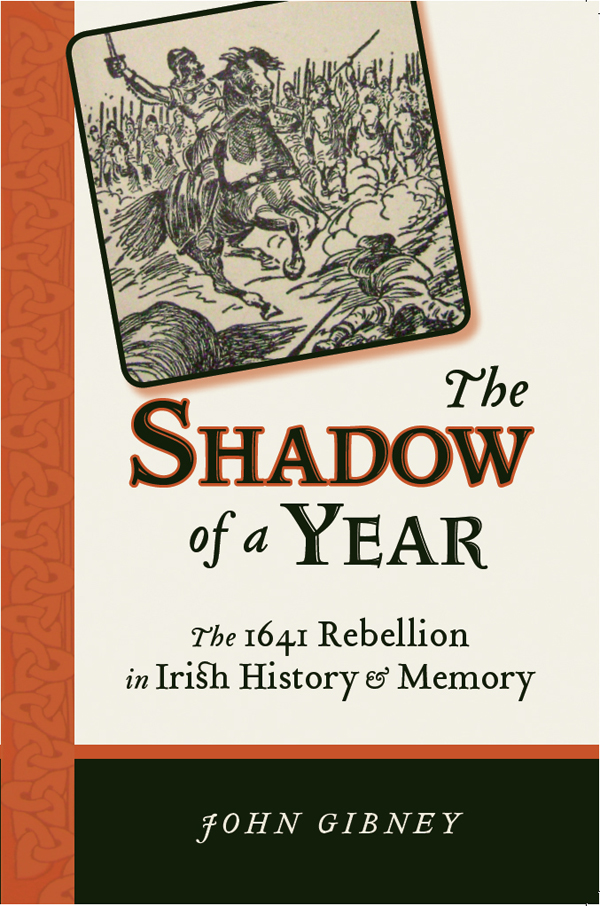

The Shadow of a Year

The 1641 Rebellion

in Irish History and Memory

John Gibney

The University of Wisconsin Press

Publication of this volume has been made possible, in part,

through support from the Anonymous Fund

of the College of Letters and Science

at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

The University of Wisconsin Press

1930 Monroe Street, 3rd Floor

Madison, Wisconsin 53711-2059

uwpress.wisc.edu

3 Henrietta Street

London WC2E 8LU, England

eurospanbookstore.com

Copyright 2013

The Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any format or by any means, digital, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, or conveyed via the Internet or a website without written permission of the University of Wisconsin Press, except in the case of brief quotations embedded in critical articles and reviews.

Printed in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Gibney, John, 1976

The shadow of a year: the 1641 rebellion in Irish history and memory /John Gibney.

p. cm. (History of Ireland and the Irish diaspora)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-299-28954-6 (pbk.: alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-299-28953-9 (e-book)

1. IrelandHistoryRebellion of 1641 Historiography.

2. IrelandHistoriography. I. Title.

II. Series: History of Ireland and the Irish diaspora.

DA943.G42 2013

941.506 dc23

2012010169

I admired the histories of the late Professor J. C. Beckett, especially the clarity of his writing, and when we met and I told him so, he was glad. As he thanked me, he remarked, Of course, theyre prejudiced, with a very sly twinkle. What this has always seemed to me to imply is that there is no such thing as a true history. Each is a version of what has taken place, and everybody who writes is coming from somewhere.

John McGahern Contents

Contents

Illustrations

Acknowledgments

Most of the research and and much of the writing of this book took place under the auspices of a Government of Ireland fellowship held at the Moore Institute, National University of Ireland, Galway. Earlier versions of parts of the text have been published as Facts Newly Stated :John Curry, the 1641 Rebellion, and Catholic Revisionism in Eighteenth-Century Ireland, 174780, ire-Ireland: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Irish Studies 44, no. 34 (Fall/Winter 2009): 24877; Walter Loves Bloody Massacre: An Unfinished Study in Irish Cultural History, 16411963, Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy 110C (2010): 21737; and Protestant Interests? The 1641 Rebellion and State Formation in Early Modern Ireland, Historical Research 84 (Feb. 2011): 6786. I would like to thank, respectively, the Irish American Cultural Institute, the Royal Irish Academy, and the Institute of Historical Research for permission to reproduce this material. I would also like to thank the Board of the British Library, the Board of the National Library of Ireland, the Board of Trinity College Dublin, Dublin City Archives, and the Honourable Society of Kings Inns for permission to quote from unpublished material in their possession.

On a personal level, a number of people made my life much easier in the course of working on this book, most especially Nicholas Canny, Carmel Connolly, Emily Cullen, Eamon Darcy, Kevin Forkan, Ted McCormick, Edward Madigan, Christopher Maginn, Brian O Conchubair, Grace OKeefe, Kate OMalley, Orla Power, and Jim Smyth, who all provided encouragement and support of one kind or another. Karl Bottigheimer generously responded to my query about the late Walter Love. Aidan Clarke, Christopher Fox, and Hiram Morgan provided me with unpublished material. I naturally wish to thank the staffs of the various libraries that I used in the course of my research, but I should single out Aedin Clements (Notre Dame), Kieran Hoare (National University of Ireland, Galway), and Gerry Kavanagh (National Library of Ireland) for going above and beyond the call of duty. Elizabethanne Boran, Eamon Darcy, Kevin Forkan, Brian Hanley, Jason McHugh, James McConnel, Robin Usher, and Kevin Whelan provided me with all kinds of arcane references and sources. Brendan Kane furnished me with a copy of a useful book andJane Ohlmeyer kindly submitted to an interview. Tommy Graham extended invitations to discuss the topic before audiences in Letterkenny, Derry, the National Library of Ireland, and the Electric Picnic in Stradbally; Micheal O Siochru invited me to speak to another audience at Trinity College Dublin. Guy Beiner commented on the introduction, and Aidan Clarke provided me with a forensic commentary on an earlier version of the manuscript, thereby improving it immeasurably. James S. Donnelly nudged it toward the finishing line with exemplary patience. Eileen ONeill prepared the index. Breandan Mac Suibhne deserves some credit for the title whether he likes it or not. I can only apologize to any colleagues or friends whose assistance I have forgotten. Finally, I owe profound debts to my family and, last but never least, to Liza Costello.

The Shadow of a Year

Introduction

On 22 October 2010, in the Long Room of Trinity College Dublin, Mary McAleese and Ian Paisley launched an exhibition about the Irish rebellion of 1641. On the face of it, they were an unlikely duo. Prior to her election as president of the Republic of Ireland, McAleese (a Belfast Catholic whose family home had been burnt out by loyalists in the 1970s) was perceived by some to represent particularly conservative forms of Irish Catholicism and nationalisma tribal time bomb, as one commentator had put it. As for Paisley, despite his transition to a seemingly mellow old age, he remained the epitome of an unyielding Protestant loyalism, whose career as both demagogue and Democratic Unionist leader was synonymous with the Troubles and had indeed been an integral part of them. Hence the existence of what might be, to a casual observer, an incongruous double act: between them, McAleese and Paisley represented the opposing political and religious traditions on the island of Ireland, from which the principal actors in the conflict in Northern Ireland had sprung over the previous five decades.

But this was the entire point of their presence, and on this occasion both were in a gracious mood. The conflict that erupted in Northern Ireland had been the latest manifestation of an enduring historical dichotomy between Catholic and Protestant on the island of Ireland. The seemingly atavistic nature of this conflict arose in part from the fact that it had never been adequately resolved and had continued to fester after being largely corralled into the six counties of Northern Ireland following the British partition of 1920. But the ultimate origin of such sectarianism is to be found long before the twentieth century. From the latter half of the sixteenth century onwards, Ireland was reconquered by English governments based in Dublin. In the aftermath large tracts of the country, especially in the northern province of Ulster, were colonized in the early decades of the seventeenth century by tens of thousands of British settlers, the majority of whom were Protestants of one kind or another. The exhibition being launched by McAleese and Paisley concerned the single most significant event of this period: the rebellion of 1641, in which Irish Catholics rose up against the British Protestant colonists who were seen to have supplanted them. They were assumed to have done so with appalling brutality, and so the insurrection of 1641 has traditionally been viewed as the first explicitly sectarian conflict in Irish history. It has been remembered as the first of many such conflicts, but the launch of this exhibition in Trinity was more concerned with how it had been